There is a clear and growing appetite within the investor community to ensure that investments deliver positive outcomes for people and the planet, but signatories’ sustainability outcomes practices could improve significantly in several areas.

Increasingly, clients, beneficiaries, policy makers and other stakeholders are requiring investors to align their investment and ownership decisions with the broader objectives of society, including those set out in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the Paris Agreement and the International Bill of Human Rights.

In parallel, investors are recognising that the real-world, sustainability outcomes connected to their investment activities can feed back into the financial risks they face.

We asked signatories how they are embedding sustainability outcomes considerations in their investment activities for the first time in the 2021 Reporting Framework, and this paper provides the first insights of its kind into what they told us.

Given the recent nature of this development, our analysis provides an overarching picture of sustainability outcomes practices among PRI signatories, rather than highlighting individual approaches.

This analysis reflects PRI signatories’ practices at the time the data was collected during the PRI’s 2021 reporting cycle. We acknowledge that these practices may have evolved since then but see this output as a useful starting point to better understand how signatories have started developing their approach to considering sustainability outcomes.

Signatories’ reporting on sustainability outcomes shows that there is a clear and growing appetite within the investor community to ensure that investments deliver positive outcomes for people and the planet. However, as our analysis also indicates, there are several areas where signatories’ practices around sustainability outcomes could improve significantly.

We hope the insights provided will help signatories – and the wider industry – to do so, ultimately helping such practices become a mainstream part of responsible investment.

Key findings

- Of the 2,796 investment manager and asset owner signatories that reported, two-thirds identified one or more positive or negative sustainability outcome connected to their investment activities. However, only 33% said they have proactively taken action to increase or decrease these outcomes.

- Half of PRI signatories reported using the SDGs to identify and contextualise the sustainability outcomes of their activities.

- A smaller proportion (17%) referred to specific human rights frameworks, such as the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights or the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, indicating that human rights outcomes were still rarely assessed in a systematic way across investment activities at the time of reporting.

- Signatories that reported taking action on sustainability outcomes did so primarily in relation to climate change. They also prioritised sustainability issues with relatively standardised and quantifiable metrics, such as energy, gender equality, public health and water and sanitation.

- Among the 945 signatories that had not yet identified sustainability outcomes, half were intending to do so in the future.

- Only 67 signatories chose to make public their reported responses related to how they manage sustainability outcomes throughout their investment process (i.e., from identifying outcomes to setting targets and tracking progress).

- Overall, the data collected in 2021 suggests that target setting on sustainability outcomes is still a nascent practice among PRI signatories. Reported targets often lacked essential information, such as metrics, a deadline or a baseline, making it difficult to determine whether signatories’ efforts are consistent with global sustainability goals and thresholds.

- Among the targets reported, 46% had a short-term deadline (before 2022) and most of them were process-oriented, focusing on stewardship activities or changes in signatory organisations’ internal processes.

- Investors were 12% more likely to set and describe sustainability outcomes targets in their reporting for every year they were a PRI signatory.

- Signatories investing in real estate were approximately twice as likely to describe targets compared to those reporting on a more diverse mix of asset classes.

Introduction

Clients and beneficiaries, policy makers and other stakeholders are increasingly requiring investors to align their investments with the global sustainability objectives of society, including those set out in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the Paris Agreement and the International Bill of Human Rights.

Simultaneously, some investors recognise that financial returns depend on the stability of social and environmental systems. Institutional investors – especially those that are focused on long-term financial returns – have a responsibility to consider whether such system-level risks are relevant to their ability to meet their legal obligations and objectives and, if so, how they can mitigate these risks.[1]

To meet these expectations and responsibilities, investors need to understand and manage the real-world, sustainability outcomes connected to their investment activities.

Sustainability outcomes include those that:

- must be addressed for economies to operate within planetary boundaries, such as climate change, deforestation, and biodiversity loss;

- must be in place to drive inclusive societies, such as human rights (including decent work), diversity, equity, and inclusion; and

- are needed in corporate cultures to ensure sustainability performance, such as tax fairness, responsible political engagement, and anti-corruption measures.

These outcomes are understood in the context of – and assessed against – global sustainability goals and thresholds, including the SDG targets and indicators, the Paris Agreement, and the International Bill of Human Rights.

To support progress toward these global sustainability goals and thresholds, investors should seek to decrease negative outcomes and increase positive outcomes arising from their actions.

To better understand how investors consider sustainability outcomes in their investment and stewardship decisions, we introduced a set of new indicators in our 2021 Reporting Framework. These indicators reflect the five-part framework presented in our Investing with SDG Outcomes report, published in 2020.

We hope the insights presented in this paper, based on an analysis of the 2021 reporting data, will ultimately help such practices become a mainstream part of responsible investment. Where relevant, we also highlight how signatories could improve their practices and identify useful resources to do so.

PRI Reporting Framework

PRI reporting is the largest global reporting project on responsible investment. PRI signatories are required to report on their responsible investment activities annually (following a grace period in their first year of joining). Read more about reporting and assessment.

For definitions of the terms used in this paper, readers should refer to the PRI Reporting Framework Glossary.

Methodology

We analysed the responses of 2,796 investment manager and asset owner signatories that reported to the PRI in 2021. The data presented in this article comes from two Reporting Framework modules: Investment and Stewardship Policies (ISP) and Sustainability Outcomes (SO).[2]

The ISP module aimed to capture signatories’ overall approach to responsible investment. It was mandatory for all reporting signatories to report on this module, regardless of their asset class mix, which responsible investment strategies they used or where they were headquartered.

It included a small number of indicators focused on how signatories identified and set policies on sustainability outcomes across their organisation. These indicators were aligned with the first two steps of the PRI’s five-part framework on SDG outcomes: identifying outcomes and setting policies and targets.

Signatories that reported how they determined their most important sustainability outcomes in the ISP module could then choose to complete the SO module.

The SO module focused on what investors are doing to advance sustainability outcomes. It only included indicators that were not assessed, were voluntary to disclose and were mostly qualitative. Of all the signatories that reported to the PRI in 2021, 44% accessed the SO module but very few of them responded to all 31 indicators available in it.

Signatories could also choose whether to make their responses to each indicator of the SO module public. Only 67 signatories publicly reported on the majority (at least 80%) of the indicators, while 142 signatories also reported on a similar proportion of indicators but chose to keep their responses private.

We analysed the responses quantitatively to determine how they varied by investor type and geography, and used qualitative methods to identify recurrent themes, trends, and patterns within signatories’ text responses.

This paper follows the structure of the ISP and SO modules, first focusing on identifying sustainability outcomes, then on adopting related policies and targets, and finally looking at how investors can take action on sustainability outcomes.

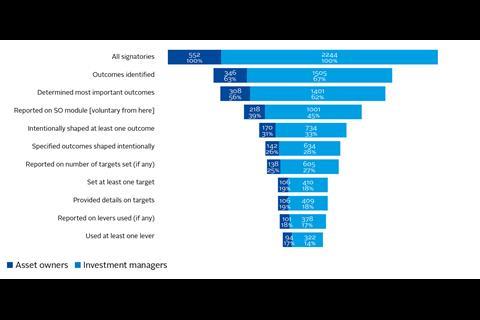

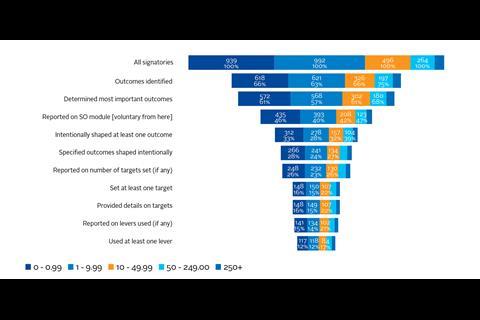

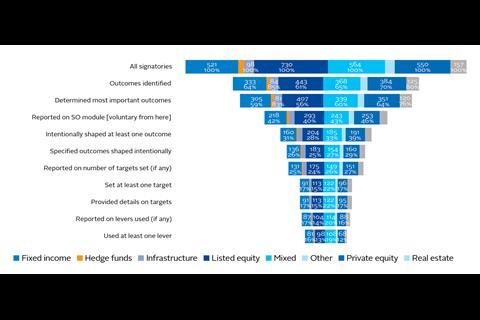

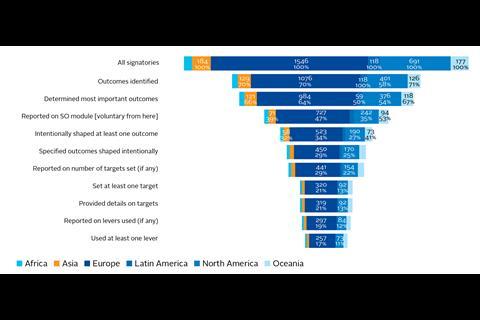

Figure 1: Sustainability outcomes indicators: uptake per investor type, AUM bracket, main asset class reported on and HQ region

Identifying sustainability outcomes

All investment activities – investment and stewardship decisions – are connected to positive and negative outcomes in the world. Some may be unintended, others might be unknown.

Two-thirds of all PRI reporting signatories indicated that they had already identified one or more sustainability outcome arising from their investment activities in 2021.

Tools and frameworks used to identify sustainability outcomes

There are several tools and frameworks that investors can use to identify the sustainability outcomes connected to their investment activities.

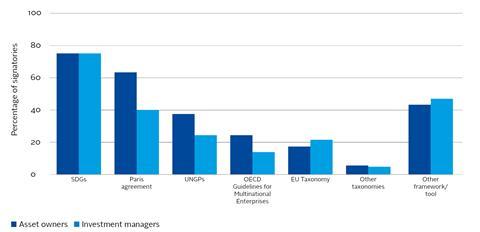

More than half (1,621) of all PRI reporting signatories said they use at least one of the internationally recognised frameworks suggested by the PRI (i.e., the SDGs, the Paris Agreement, the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises or the EU taxonomy) to do so. Of those, 76% reported using the SDGs. This trend was common across all regions and investor types.

Signatories could also list other tools they deemed useful for identifying the sustainability outcomes of their investments. They frequently mentioned tools such as their proprietary environmental, social and governance (ESG) frameworks, the United Nations Global Compact, the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) or the GRESB.

Figure 2: Tools and frameworks used to identify outcomes across signatory type

Where sustainability outcomes are identified

Sustainability outcomes can be identified at the level of a particular asset, economic activity, company, sector, country, or region. The level(s) that investors choose to identify and assess will influence the actions they take to address them.

Nearly two-thirds (215) of the asset owners that said they identify sustainability outcomes reported doing so at the company level, compared with 73% of investment managers.

Ultimately, to drive outcomes globally that are consistent with sustainability goals and thresholds, most investors will need to progress towards focusing on outcomes across their portfolios. To do so, they will need to have processes in place to collect, measure and aggregate the outcomes of their activities.

Only 11 signatories reported that they identify company-level and portfolio-level sustainability outcomes, suggesting that they likely have a more complete picture of the sustainability outcomes connected to their activities.

Reasons for not identifying sustainability outcomes

Nearly half of the 945 signatories that do not yet identify sustainability outcomes reported that they intend to in the future.

The three most common reasons given for not identifying sustainability outcomes reflect the broader challenges some signatories face to invest responsibly:

- Being too early in their responsible investment journey to consider sustainability outcomes

PRI signatories that are still formalising their responsible investment policies and approaches more broadly are prioritising assessing the financial materiality of sustainability risks over sustainability outcomes, and do not yet consider the relevance of the latter for investment performance.

- Insufficient and incomplete sustainability outcomes-relevant data

Accessing accurate and meaningful sustainability data to assess the outcomes on people and the planet connected to investments continues to be challenging for signatories. They mentioned facing (i) disclosure limitations in specific markets; (ii) a lack of standardised frameworks and guidelines; and (iii) difficulties in attributing outcomes to their stewardship and investment activities.

- Lack of organisational resources and capacity

This concern was raised throughout the PRI Reporting Framework by investment managers with less than US$1bn in AUM.

Improving practices

To improve how they identify the outcomes connected to their investments, investors could:

- combine various ESG integration and impact management tools to assess outcomes over different time horizons; and

- consider sustainability outcomes holistically – acknowledging the interdependencies between positive and negative outcomes, including in relation to human rights.

Resources

- The PRI’s SDG Investment case is a starting point for investors that want to better understand why the SDGs are relevant to investors, why there is an expectation that investors will contribute and why they should want to.

- Investing with SDG outcomes goes further, highlighting that a focus on sustainability outcomes can also feed back into portfolio performance, and into the resilience of the financial system itself (see p.8 – p.9).

- The Impact Management Platform helps investors to identify the sustainability outcomes connected to their activities.

- A Legal Framework for Impact highlights how investors in different jurisdictions are broadly permitted – and may even be required – to address sustainability outcomes, particularly when they are relevant to financial returns.

Adopting policies and setting targets

A key element for signatories wanting to make the outcomes of their activities consistent with global sustainability goals and thresholds is to adopt and implement relevant policies and targets. In 2021, just over two-fifths (1,206) of all PRI reporting signatories said they had a policy, or some guidelines, dedicated to sustainability outcomes.

Sustainability outcomes policies

Most signatories include their general approach and commitment towards sustainability outcomes in their responsible investment policy. Less than a quarter (683) said they include their approach to sustainability outcomes in other strategic documents, such as their exclusion or stewardship policy, or in separate guidelines on asset classes or specific topics, such as human rights, climate change or the SDGs.

Policies that refer to widely recognised frameworks can help guide investors’ actions on sustainability outcomes. Indeed, 38% of all PRI reporting signatories said they refer to at least one of those suggested by the PRI (the SDGs, the Paris Agreement, the UNGPs, the OECD guidelines) in their sustainability outcomes policies.

References to the SDGs were common across all regions and investor types but mentions of other frameworks differed notably between signatories. For example, 79% of asset owners with sustainability outcomes-focused policies referred to the Paris Agreement compared to 46% of investment managers. Furthermore, among large investors (those with assets of US$250bn or more), 90% mentioned the Paris Agreement, compared to 33% of investors managing US$1bn or less.

A smaller proportion of signatories (17%) said they refer to specific human rights frameworks in their policies – such as the UNGPs (57% of asset owners and 35% of investment managers with policies) and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (38% of asset owners and 18% of investment managers with policies). This indicates that investors need to further develop their practices to ensure they systematically assess human rights outcomes across their activities.

Types of sustainability outcomes reported

Signatories could list up to 10 sustainability outcomes connected to their investment and stewardship activities that they have decided to take action on. While asset owners and investment managers both disclosed an average of 4.5 outcomes, less than 3% of all PRI reporting signatories listed 10.

Signatories’ reported outcomes often referred to the SDGs, with 22% explicitly referring to an SDG name (e.g., affordable and clean energy) or number (e.g., SDG 7).

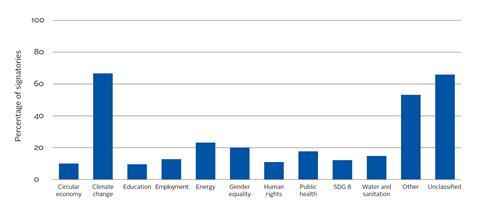

Where possible, we classified signatories’ sustainability outcomes into fixed categories. The most common among them were related to climate change, energy, gender equality, public health and water and sanitation.[3]

These align with high-profile ESG topics (e.g., incidents that receive frequent media coverage, such as COVID-19 or the #MeToo movement), and those that have relatively standardised and quantifiable ESG metrics (e.g., greenhouse gas emissions, board diversity, water use, energy efficiency).

Figure 3: Percentage of signatories reporting outcomes per category[4]

Target setting

Setting targets on sustainability outcomes was an infrequent practice among reporting signatories, with less than 19% reporting that they have a target and providing details on it.

When accounting for signatory characteristics (i.e., investor type, region, AUM), investors were 12% more likely to set and describe sustainability outcomes targets in their reporting for every year they were a PRI signatory. Furthermore, signatories focused primarily on real estate were approximately twice as likely to describe targets compared to those reporting on a more diverse mix of asset classes.

We identified two common types of sustainability outcomes targets:

- Targets focused on stewardship activities, such as encouraging investees to adopt new policies or increase disclosure.

- Targets focused on increasing sustainability outcomes considerations within signatories’ organisations. These included adopting outcome-relevant policies to guide investments, ensuring stricter due diligence processes across their operations or outperforming specific benchmarks (e.g., on carbon intensity, ESG scores).

These targets are process-oriented and indirectly linked to sustainability outcomes. Generally, signatories were confident that these targets could be met in the near future – 46% were immediate (with a deadline before 2022). One-tenth of all targets reported (14%) had a deadline before 2021, although it was not always clear if these had been met at the time of reporting. The focus on past and short-term targets indicates that signatory reporting on sustainability outcomes is not yet a statement of long-term ambition.

A smaller sample of targets were more precise and referred to some of the most reported outcome categories, such as climate change (emission reduction targets and net-zero commitments), gender equality (increasing gender diversity at board level) and water and sanitation (reducing water consumption in the portfolio).

Their descriptions were more outcome focused, but like the other targets, most of them were not assessable or time bound. Indeed, many were not associated with a clear metric or commitment and focused instead on incremental improvements (e.g., achieving annual water savings rather than reducing water consumption by a specific percentage).

Signatories did not describe a target for nearly half of the sustainability outcomes disclosed, either because they had not set any, or because they did not respond to the relevant indicators in the module.

This makes it difficult to compare signatories’ target setting practices. Some sustainability outcomes had particularly low numbers of targets associated with them – for example, SDG 9 (industry, innovation, and infrastructure) and SDG 10 (reduced inequality). This may be explained by a lack of relevant sustainability data for these outcomes, a greater focus on tracking qualitative progress not linked to a numerical target, or that action on these outcomes remains more aspirational at this stage.

Progress tracked

Signatories said they had processes to track intermediate performance and progress for around 85% of the sustainability outcomes targets reported.

However, they often reported on progress without providing a baseline of current sustainability performance, making it difficult to determine whether their efforts are consistent with global sustainability goals and thresholds.

Signatories’ reporting largely focused on tracking changes in processes (e.g., adopting a new policy, the number of investees disclosing their CO2 emissions) and seldom reflected on the real-world outcomes for people and the environment.

These observations even apply to climate change – the issue for which signatories provided the most complete and comparable targets. Only a handful of signatories reported on quantitative progress – for example, by providing a clear measure of reduction of a portfolio’s carbon footprint or CO2 emissions.

Improving practices

To improve how they set sustainability outcomes targets and track progress, investors could:

- set actionable, relevant and time-bound targets that guide action on sustainability outcomes and rely on clear commitments and deadlines for assessment; and

- clarify how these targets relate to global sustainability goals and thresholds.

Ultimately, investors should move from only setting process-based targets toward also setting outcome-based targets.

Resources

- The tools listed in Investing with SDG outcomes: a five-part framework can be a starting point for signatories wanting to set targets and track progress on sustainability outcomes within their portfolios.

- The Target Setting Protocol from the Net Zero Asset Owners’ Alliance provides guidance on setting net-zero targets for different asset classes or high-emitting sectors.

- Why and how investors should act on human rights provides guidance on how to prevent and mitigate actual and potential negative outcomes for people.

- The Impact Management Platform provides additional guidance for investors that want to set targets for ongoing management of sustainability outcomes.

Taking action on sustainability outcomes

Investors can take action on sustainability outcomes in three ways:

- Investment decisions – using information on sustainability outcomes in the investment decision-making process;

- Investee stewardship – using their individual or collective ownership rights or position(s) in an asset to influence the activity or behaviour of (potential) investees;

- Engaging with policy makers and key stakeholders – on a range of industry-level or wider regulatory and legislative developments to promote sustainability considerations in financial markets.

Almost one-third (1,851) of all PRI reporting signatories said they had already started reducing the negative outcomes or increasing the positive outcomes related to their investment activities in 2021.

Investment decision making

Investors can use information on sustainability outcomes to inform asset allocation, portfolio construction and security selection.

Negative screening was the practice most mentioned by signatories in relation to considering sustainability outcomes in their investment decisions. This indicates that signatories are predominantly considering sustainability outcomes to avoid exposure to negative outcomes when making new investments.

This echoes a broader trend in signatories’ ESG incorporation practices, with 41% reporting using minimum standards of business practice, based on international norms (OECD guidelines, the UN Human Rights Declaration, Security Council sanctions or the UN Global Compact), as part of their exclusion policy.

A few signatories reported delivering positive outcomes through thematic investment. Their approaches included:

- assessing the potential outcomes of an opportunity before making an investment using a specific methodology;

- relying on global, regional, or local goals to determine investment areas and geographies most in need; and

- setting dedicated strategies to achieve positive outcomes in individual asset classes.

Divestment and sustainability outcomes

Signatories rarely mentioned divestment in their reporting. When they did, it was almost exclusively with reference to high-emitting industries and reducing exposure to negative climate outcomes.

Although divestment can reduce investors’ exposure to specific (existing) holdings, it is unlikely to have a discernible impact on their portfolio-wide exposure, particularly where the risks or issues are systemic.

In such cases, divestment reduces investors’ ability to mitigate the risks and negative outcomes posed to their portfolios and beneficiaries. Indeed, where the poor sustainability performance of a subset of investees exacerbates the risks faced in their broader portfolios, investors should not view divestment as a way to eliminate those risks.

This is explored further in Discussing divestment: Developing an approach when pursuing sustainability outcomes in listed equities.

Investee stewardship

Once targets have been set for specific outcomes, investors can act on them by using active ownership tools, such as voting and engagement, including participating in collaborative strategies.

Just under 300 signatories specified how they used stewardship with investees to make progress on sustainability outcomes. Whether individual or collective, their activities focused on the same outcome categories: climate change, energy, and human rights issues, particularly gender equality and public health.

Some signatories reported undertaking human rights-focused stewardship even when they were not explicitly prioritising human rights as an outcome.

According to the data reported, signatories tend to use stewardship tools individually, rather than collectively. The most frequent type of individual stewardship activity reported was voting in shareholder meetings on proposals and resolutions that advance sustainability outcomes considerations or opposing those that undermine them.

Many also use their representation on investee boards and board committees to shape sustainability outcomes. Only seven signatories reported using litigation as an escalation tool on some of their sustainability outcomes.

Two hundred and fifty signatories provided at least one example of engaging with investees to make progress on their sustainability outcomes. Most of these targeted one investee at a time, showing that signatories prefer to work on outcomes on a case-by-case basis.

The examples reported largely focused on encouraging investees to adopt new outcome-relevant policies and setting targets.

Nearly half of the signatories (47%) reported engaging with investees on data quality issues and reporting concerns, for example by running campaigns to collect data on sustainability topics or meeting with them to understand how they assess materiality and which sustainability metrics they use.

Few examples highlighted actual real-world improvements in outcomes due to changing investees’ business practices.

Other engagement examples focused on encouraging investee companies to adopt policies and commitments related to specific sustainability topics or raising governance concerns related to executive compensation or board composition, for example.

Although individual engagement is more common, some PRI signatories also reported on their collaborative engagement approach. Some 131 signatories said they preferred engaging collaboratively to make progress on sustainability outcomes, while others said they do so when individual efforts have been unsuccessful (16) or where collaboration would minimise the costs involved (3).

The most common way signatories contributed to collaborative initiatives targeting sustainability outcomes was by leading coordination between investors and by contributing to pro-bono advice, research and/or financial reports.

Engaging policy makers and other stakeholders

Public policy critically affects the stability and sustainability of financial markets and of social, environmental and economic systems. It also drives large-scale action that can be harnessed to make progress on sustainability outcomes.

Public policy engagement is therefore a natural and necessary extension of investors’ responsibilities and efforts to take action on sustainability outcomes.

Fewer than 9% of all PRI reporting signatories provided details of policy maker engagement – either individually or collaboratively. Those that did mostly focused on climate change, energy and human rights issues, particularly public health and employment outcomes.

Signatories generally said they engage with policy makers by responding to national and regional policy consultations and signing open letters.

Investors need to have clear governance processes in place to ensure engagement with policy makers is aligned with their sustainability outcomes targets.

Only 8% of all PRI reporting signatories described their governance processes, mostly using generic language and referring to their broader ESG and responsible investment policies. It is therefore difficult to assess if these systematically ensure that their engagement with policy makers is aligned to their sustainability outcomes policies and targets.

Engaging with reporting organisations and other standard setters is another avenue for investors seeking to embed sustainability outcomes considerations within their investment decisions.

Only 13% of all PRI reporting signatories said they do so, targeting standard setters including the SASB[5], the TCFD and CDP, but further information is needed to understand what these engagements are focused on.

Resources

- The investor case for responsible political engagement outlines why investors working towards sustainability objectives must also ensure that their portfolio companies are conducting political engagement in a responsible manner that does not conflict with their objectives.

- Responsible political engagement: stewardship practices and challenges looks at how investors can identify and assess their investees’ political engagement activities and integrate political engagement into their stewardship activities.

- The PRI’s Global Policy Reference Group supports signatories’ public policy engagement on responsible investment topics.

Next steps

We will continue to support signatories that are seeking to identify and take action on sustainability outcomes while remaining firmly grounded in fiduciary duty. We will do so by adding to our resources on sustainability outcomes.

We will provide further guidance and support in the following areas:

- Reporting and Assessment: we will refine the definitions and indicators within the PRI Reporting Framework and guide signatories to report on the PRI 2023 sustainability outcomes module, including on human rights and climate outcomes and target setting.

- Managing sustainability outcomes:

- by collaborating with partner organisations, including the Impact Management Platform and Global Investors for Sustainable Development Alliance and developing content on managing sustainability outcomes;

- by further developing our work programme on human rights including through Advance, a PRI-led stewardship initiative, where institutional investors will use their collective influence with companies and other decision makers to drive positive human rights outcomes for workers, communities and society; and

- by further developing our work programme on Active Ownership 2.0, including how asset owners can better evaluate their external managers’ stewardship practices when pursuing sustainability outcomes.

- Case studies: we will develop additional case studies showing how signatories are identifying and acting on sustainability outcomes connected to their investment activities.

Downloads

References

[1]See Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, the PRI, United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative, Generation Foundation (2021), A Legal Framework for Impact: Sustainability impact in investor decision-making (p.154 – p.192) and (2022) UK: Integrating sustainability goals across the investment industry.

[2]Indicators covered in this article include ISP 40, 41, 43, 43.1, 44, 44.1, and SO 1, 2, 3.1, 5, 5.2, 7, 8, 11, 13-16, 17-19, 23.

[3]We developed these categories based on the most frequent words used by signatories in their responses. As such, we list human rights, gender equality, health, and employment as distinct categories, even though these interlinked issues are all captured in human rights frameworks and can all be understood in relation to the idea of human rights – that people have a universal right to be treated with dignity.

[4]While relying on free-text answers avoided leading signatories in which outcomes they chose to report, we could not classify 25% of the answers as a result, represented in Figure 3 under “unclassified”.

[5]SASB is now part of the IFRS but was a separate entity during the 2021 reporting cycle.