Companies should map their supply chains, by geography and by product, and assess labourrelated risks in the supply chain, by geography and by product.

Background

To manage labour practices in their supply chains, companies need to understand where and who they source from, as well as any associated risks. This is particularly relevant in agriculture, as supply chains are complex and multi-tiered and many companies lack an understanding of the situation at farm level, where most labour breaches occur. Reporting the names of suppliers increases transparency and accountability for both the company and suppliers.

Engagement questions

Opening questions

Supply chain mapping

- Does the company understand who its suppliers and sub-suppliers are, down to farm level?

- Does the company fully disclose its sourcing, by product and geography?

Geographic and product risk assessment

- Does the company have a process in place for assessing risk, by product and geography?

- Does it at least cover all high-risk countries and/or most sourced products?

- How does the company prioritise which labour related risks to focus on?

Follow-up questions

Length of supply chain

- Is the company able to demonstrate that it understands the length and complexity of its supply chain beyond its direct suppliers (e.g. different tiers of its supply chain, total number of suppliers in all tiers)?

List of suppliers

- Does the company know the names and locations of its direct suppliers and sub-suppliers? To what extent are these disclosed (e.g. does the company at least disclose names of suppliers of key crops, suppliers from highrisk countries, or suppliers with the highest purchasing volume)?

Geographic and product risk assessment

- How does the company prioritise which risks to focus on?

- In the last three years, has the company conducted at least one risk assessment that examined social issues in the supply chain focused on a specific commodity or region?

- Does the company disclose a summary of the assessment results (e.g. type of suppliers, countries/ geographical areas considered at risk and types of risks identified)?

- If child labour, forced labour, discrimination, working conditions and/or trade union rights are not included, is the company able to explain why not?

Company examples

Length of supply chain: The Canadian fast food restaurant Tim Hortons illustrates the six key levels of its coffee supply chain. It includes farmers (from small-holders to large estates), intermediaries (i.e. traders that help farmers get their coffee to the market), in some cases organisations such as farmer associations or cooperatives, followed by exporters, importers, internal and third-party roasters.

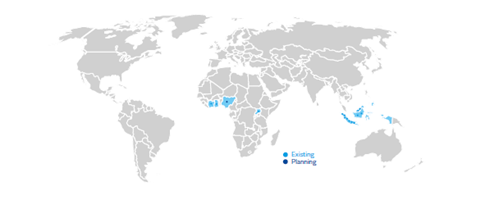

Disclosure of geographic and product sourcing, and of supplier names: In order to implement its No Deforestation, No Peat and No Exploitation Policy, in early 2014 the Singaporean agribusiness group Wilmar started to map its supply chain, focusing particularly on palm oil sourced from Indonesia and Malaysia. Wilmar has a dashboard microsite for its palm oil supply chain, developed in collaboration with The Forest Trust. The site lists the names and locations of Wilmar’s palm oil mill suppliers in Indonesia and Malaysia, and is updated on a quarterly basis to reflect increased traceability and changes in suppliers. The mill details are used in conjunction with data and information on land use, soils and social issues to prioritise assessment visits. Wilmar also has a mapping function on its website that shows from which countries it sources tropical oils, oil seeds and grains. Wilmar is building a vertically integrated supply chain for sugar, and has disclosed the names of the suppliers it has acquired or in which it holds a stake.

Tools and further guidance

The following resources provide guidance for companies on how to map their supply chains:

- SAI, IFC (2010) . Measure & Improve Your Labor Standards Performance. Performance standard 2 handbook for labor and working conditions, chapter on eLabor Standards Performance in Your Supply Chain f: Mapping Your Supply Chain, p. 70ff.

- BSR, UN Global Compact (2015) - Supply Chain Sustainability - A Practical Guide for Continuous Improvement, Second Edition, chapter 4. Determining the Scope: Supply Chain Mapping, p. 30ff.

- Food and Drink Federation (2012) . Sustainable Sourcing: Five Steps to Managing Supply Chain Risk, see the following sections: 1. Map your supply chain, 2. Identify impacts, risks & opportunities, 3. Assess and prioritise your findings; p. 3-5.

- Enodo Rights: Yousuf Aftab and Audrey Mocle (2015) . A Structured Process to Prioritize Supply Chain Human Rights Risks. A Good Practice Note endorsed by the United Nations Global Compact Human Rights and Labour Working Group., see Stage 2: Understanding business involvement with adverse rights impacts, p. 14-20.

The following guide presents a step-by-step explanation on how to implement traceability programmes:

- UN Global Compact and BSR (2014) - A Guide to Traceability: A Practical Approach to Advance Sustainability in Global Supply Chains.

The following sources provide country-specific information on labour-related risks and regulation:

- The Danish Institute for Human Rights et al. Human Rights and Business Country Guide (country-specific overview of human rights issues including rights-holders at risk in the workplace and labour standards, currently covering 16 countries)

- Labour Exploitation Accountability Hub. Countries (Country information on regulation on forced labour by country, currently covering 10 countries)

Download the full report

-

From poor working conditions to forced labour - what's hidden in your portfolio?

June 2016

From poor working conditions to forced labour - what's hidden in your portfolio?

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7Currently reading

Expectation 3

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11