This guide summarises what human rights are and how asset owners and their advisers can manage them in the investment process.

The guide is split into two main parts:

Approaches asset owners can take

The guide ends with an overview of our multi-year agenda to promote respect for human rights within the financial system. Links to additional resources from this programme are included throughout the guide.

For more information, please get in touch via our ‘contact’ page or email soc[email protected]

Part 1: The relevance of human rights

Defining human rights

The idea of human rights is as simple as it is powerful: that people have a universal right to be treated with dignity. Every individual is entitled to enjoy human rights without discrimination – whatever their nationality, place of residence, sex, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, language or any other status. Human rights are interrelated, interdependent and indivisible.

Companies’ responsibility to respect human rights is based on internationally recognised human rights standards – understood, at a minimum, as those set out in the following texts:

International Bill of Human Rights(comprising the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and its two optional protocols) |

International Labour Organization’s Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work and the eight core conventions |

|

|

Examples of rights covered |

|

|

Additional instruments have set out the human rights of people belonging to particular groups or populations – for example children, ethnic or religious minorities and indigenous people – recognising that they may need specific protection to fully enjoy human rights without discrimination. Some jurisdictions also have regional and national laws with stricter requirements.1

Human rights are the foundation of the ‘social’ pillar within the term ‘ESG’. In practice, social, environmental and governance factors interlink. For example, climate change is primarily characterised as an environmental issue, but it is one that has a significant impact on human rights.

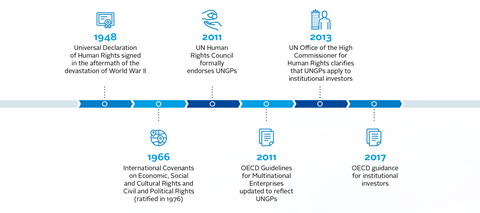

Milestones in the development of human rights standards

PRI resource

- Discussion paper | Why and how investors should act on human rights

Why human rights matter to asset owners

There are many different forces that compel asset owners to respect and protect human rights. Four key themes are explored below.

Legal responsibility

Institutional investors have a responsibility to respect human rights through a set of policy and process requirements, as set out in the United Nations Guiding Principles (UNGPs) on Business and Human Rights.

The UNGPs consist of three pillars:

| The state duty to protect | The corporate responsibility to respect | Access to remedy |

|---|---|---|

|

States must protect against human rights abuse within their territory and / or jurisdiction, including by businesses. This requires taking appropriate steps to prevent, investigate, punish and redress such abuse through effective policies, legislation, regulations and adjudication. |

Business enterprises including institutional investors should respect human rights. This means that they should avoid infringing on the human rights of others and should address adverse human rights outcomes with which they are involved. |

Allowing affected people to seek redress for any harm that they have experienced as a result of business activities is an expectation of both states and business enterprises through grievance mechanisms. |

The OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises align with the UNGPs. The OECD’s guidelines are an international legal instrument that are adhered to by many governments globally. Institutional investors can be subject to complaint cases via an OECD National Contact Point (NCP) if they fail to meet these standards. After a number of NCP cases against institutional investors, the OECD released detailed technical guidance in 2017 on how investors should comply.

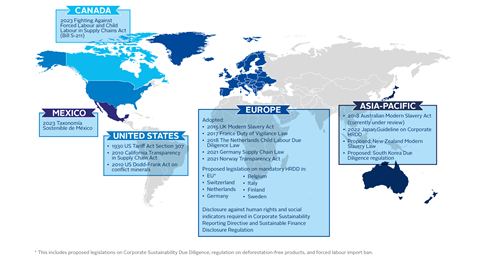

There is also region-specific regulation on human rights around the world that applies to investors. For example, in the EU, human rights disclosure obligations have already been introduced via the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) and the minimum safeguards of the EU Taxonomy. Outside of the EU, various countries have passed or proposed due diligence, supply chain transparency and modern slavery laws. (See the graphic below.)

Financial materiality

Human rights factors are relevant for investors to consider as they can impact financial returns.

There are many ways in which human rights issues can affect the performance of individual investees. For example, companies can face higher operational and legal costs due to community conflicts,4 and they can receive considerable legal penalties if they do not appropriately manage private data.5

Institutional investors are subject to system-wide (or systemic) risks whose impacts extend beyond a single company, sector, or geography. Widening income inequality – which makes it harder for groups of individuals to realise their economic and social rights – is an example of a systemic human rights issue. Greater income inequality (both within developing and developed countries) is leading to volatile economic conditions and political polarisation, which impact investment performance.6

Investors also have a role to play in allocating capital to economic activities and assets that respect human rights. In 2015 the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were adopted at a United Nations summit. The goals seek “to realise the human rights of all”.7 Substantial investment is required to meet the SDGs.8

Example of the financial materiality of human rights issues

A French court upheld charges of complicity in crimes against humanity against the cement company Lafarge in relation to actions it took to keep its plant in Syria operating following the outbreak of civil war. Lafarge, which merged with the Swiss company Holcim in 2015, admitted making payments to terrorist groups in Syria. The payments aimed to help the company secure materials and ensure its staff could continue to access its plant in the country. Lafarge was fined US$778m by the US Department of Justice in relation to the payments.

Beneficiaries’ sustainability and ethical preferences

An increasing number of asset owners’ beneficiaries are interested in ensuring their money is invested in a manner that aligns with their values,9 including respect for human rights.

For some asset owners, particularly foundations and endowments, promoting human rights for ethical reasons is core to their mission. For this reason, human rights considerations are central to how they manage their portfolios.

Reputational risk

Media organisations, NGOs and other campaigning groups track how institutional investors allocate their funds. News of asset owners’ investments being implicated in human rights abuses generates significant attention. Respecting human rights helps to safeguard against potential reputational damage.

PRI resources

Part 2: Approaches asset owners can take

All asset owners have a responsibility to respect human rights. However, the levers available depend on their resources, asset class mix and whether they manage assets internally or externally.

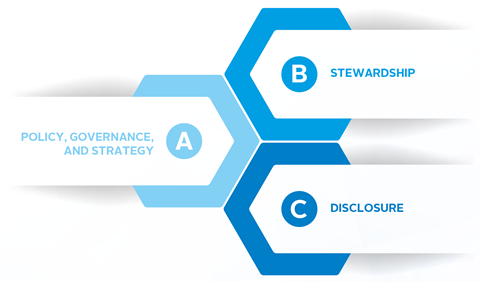

This section of the introductory guide is designed for asset owners who primarily outsource investment management. It covers the following three areas:

Institutional investors managing assets internally can refer to the list of resources at the end of this section for additional guidance on how they can act on human rights.

A. Policy, governance and strategy

PRI Principle 1: “We will incorporate ESG issues into investment analysis and decision-making processes.”

As a first step, asset owners can adopt a policy commitment to respect internationally recognised human rights. It is good practice for the policy to be:

- Approved at the most senior level;

- Communicated throughout the organisation; and

- Integrated into governance frameworks, management systems, investment beliefs, and strategies to inform investment decisions, engagement with investees and policy dialogue.

We have collated a bank of signatory human rights policy commitments that are consistent with the UNGPs. Asset owners can use these as reference points when developing their own policies.

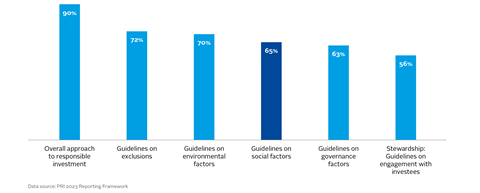

During the 2023 PRI reporting cycle, 65% of asset owners reported having publicly available policies covering social issues, as shown below.

Figure 1: PRI asset owner signatories’ publicly available policy elements

It is important that asset owners’ human rights commitments are understood and implemented by their investment managers. Alignment of approaches on human rights can be assessed during manager selection and monitoring. The below box-out provides examples of questions allocators can ask managers regarding their human rights due diligence processes. A comprehensive assessment of human rights performance would cover additional areas, such as an organisation’s human rights governance arrangements.

Example due diligence questions

- What are the key human rights issues that the investment manager will aim to address?

- How have the risks identified affected / will affect allocation decisions and stewardship activities? Give examples.

- How is progress monitored?

- How, and how often, will progress / updates be communicated?

Asset owners can use information disclosed through the PRI Reporting Framework to assess the human rights approach of their potential or existing third-party investment managers. In our guidance on human rights-relevant indicators across our reporting modules, we explain how they correspond to the three-part responsibility outlined by the UNGPs.

Allocators can also embed respect for human rights within the terms of contractual agreements. The ICGN-GISD Model Mandate provides sample clauses.

A key point to note is that the ability and responsibility to respect human rights spans asset classes. The actions an equity investor can take to manage human rights issues differs from those available to, say, a sovereign debt investor, but the responsibility remains. See the resources list at the end of this section for asset-class-specific guidance on acting on human rights.

Case study

VFMC: Tackling modern slavery through external manager engagement

Victorian Funds Management Corporation (VFMC) is an Australian asset owner. The fund states that it is committed to responsible labour practices and is against all forms of slavery.

It conducts specific due diligence on incumbent investment managers to understand how they identify, assess, and mitigate the risk of modern slavery. It also includes the issue in its pre-investment due diligence processes and instates relevant contract clauses in new investment management agreements.

Due diligence conducted in 2021 highlighted variability in managers’ understanding of modern slavery risks and consequently in the robustness of their risk-management processes. VFMC used this opportunity to educate managers on its approach and share approaches it had seen others adopt in order to raise standards of practice.

B. Stewardship

Stewardship is the use of influence to enhance and protect the overall long-term value of the assets on which clients’ and beneficiaries’ interests depend. Asset owners can conduct stewardship activities – either directly or through investment managers and other service providers – in order to honour their human rights commitments and pursue their human rights objectives.

Investors can choose to engage with a variety of different stakeholder groups on human rights issues. These include investees; external managers; policy makers; civil society and human rights experts; unions; and affected stakeholders.

Asset owners can conduct stewardship activities independently or collaborate to exercise their collective influence. We have launched the Advance initiative to enable institutional investors to work together on human rights and social issues.

C. Disclosure

Through regular reporting, asset owners can keep beneficiaries and other stakeholders informed of their human rights policies, practices and impacts. Disclosures can take many forms, including sustainability reports and publishing case studies. The PRI’s Reporting Framework allows signatories to disclose information about their human rights approach.

Public reporting on human rights indicators is increasingly mandated by lawmakers. For example, companies that meet certain thresholds, including some asset owners, are required to report under the EU’s SFDR.

PRI and external resources

- Database | Human rights benchmarks for investors: an overview

- Database | Investor human rights policy commitments: an overview

- Database | Human rights case studies

- Discussion paper | What data do investors need to manage human rights risks?

- Discussion paper | Human rights in sovereign debt: the role of investors

- Investor tool | ICGN-GISD Model Mandate

- Reporting guidance | 2023 PRI reporting guidance on human rights

- Technical guide | How to identify human rights risks: A practical guide in due diligence

- Technical guide | Human rights due diligence for private markets investors

Next steps

We have a multi-year agenda to promote respect for human rights within the financial system. To implement this, we will continue to:

- Support institutional investors to implement the UNGPs through knowledge-sharing, examples and other practical materials;

- Increase accountability among signatories via human rights questions in the PRI Reporting Framework;

- Facilitate investor collaboration via the Advance initiative to address industry human rights challenges;

- Promote policy measures that enable investors and investees to manage human rights issues; and

- Drive meaningful data that allows investors to manage risks to people.

Downloads

An introduction to responsible investment: human rights

PDF, Size 2.5 mbGuide d'introduction aux droits humains pour les investisseurs institutionnels (French)

PDF, Size 2.58 mbAn intro to RI: human rights (Chinese) 资产所有者人权入门指南

PDF, Size 2.58 mb

References

1 OHCHR (2012), The Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights: An interpretive guide, p.9-12

2 Platform on Sustainable Finance (2022), Final Report on Social Taxonomy

3 Mexican government (2023), La Taxonomía Sostenible De México

4 Harvard Kennedy School, SHIFT and the University of Queensland (2014), Costs of Company-Community Conflict in the Extractive Sector

5 Barron’s (2023), Meta Stock Dips After Getting Fined a Record $1.3 Billion by the EU

6 See OECD (2014), Trends in Income Inequality and its Impact on Economic Growth; Pepijn Bergsen et al (2022) The Economic Basis of Democracy in Europe, and Qiaoqiao Zhyu (2021), Investing in Polarized America: Real Economic Effects of Political Polarization

7 OHCHR, OHCHR and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

8 UNCTAD (2023), More investment needed to get global goals back on track

9 PRI (2021), Understanding and aligning with beneficiaries’ sustainability preferences