Investors need robust and reliable climate data to deliver and credibly report on their net zero commitments. However, there are gaps in the data currently available. This report explores where those gaps are and looks at what action could be taken by data providers and other stakeholders to build a data ecosystem that meets investor needs.

Executive summary

Context

An enormous amount of investment is required to reduce global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement. A number of investor-backed net zero frameworks and initiatives have been established to facilitate this investment. To make informed investment decisions and engage effectively with their investments, investors need robust and reliable climate data.

Investors often rely on climate data and products from third-party data providers. As the number of these providers and their products grow, investors and other stakeholders, such as regulators and standard setters, have highlighted the importance of maintaining the quality of these products, given the role that they play in decision-making by investors.

This report explores this by asking:

- What do investors need to know? Specifically, what data is needed by investors to support their commitments to reduce the real-world emissions generated by their investments?

- What is the quality and coverage of climate data offered by data providers, and what are the gaps between the data provided and investors’ data needs?

- What actions can be taken by investors, by data providers and by other stakeholders to build a data ecosystem that provides the data needed by investors to deliver and credibly report on their net zero commitments?

This report builds on previous literature by explicitly analysing what investors are looking for – using the requirements of investor initiatives as the basis for this analysis – against the landscape of available climate data and products. It highlights gaps between these needs and the data that was available at the time of the research. The research process involved:

- A review of the literature on investor climate data needs.

- A review of the requirements of the 17 major investor-led net zero and similar climate change frameworks and initiatives.

- A review of 62 climate data products, provided by 19 data providers, in September/October 2022, followed by a feedback stage where the data providers were able to review the assessments of their products.

- Interviews, in October 2022, with 16 institutional investors around the world about their climate data needs.

We recognise that the market is continuing to rapidly develop, with considerable innovation in the data provision space. Accordingly, we conducted a further round of engagement with a number of data providers in April/May 2023 to validate our recommendations.

What do investors need to know?

The research finds that investors need to know:

- To what extent are individual investments (e.g., companies) aligned with net zero goals? To assess this question, investors need information on current emissions, current exposures to opportunities (e.g., climate solutions) and to risks (e.g., fossil fuels), the actions being taken to deliver real-world emission reductions, and the quality of an investment’s climate change governance.

- To what extent will individual investments be aligned with net zero goals in the future? Here, investors need information on future emission trajectories, emission targets and the alignment of the investment’s strategy with the goal of delivering real-world emission reductions.

- Is the current position of their portfolios and funds aligned with their net zero goals (i.e., in aggregate, are their investments net zero-aligned)?

- What level of emissions reductions will be required over time for their portfolios and funds to be net zero-aligned. Investors generally use net zero emission pathways to conduct these assessments.

What is the coverage and quality of climate data?

At present, the climate data providers assessed as part of the research provide reasonably good coverage of large companies (both listed companies and debt issuers) in developed markets. However, the data provider market is much less well-developed for smaller companies, for companies from emerging and developing markets, and for asset classes other than listed equities and fixed income, reflecting the coverage and quality of corporate disclosure globally. These gaps in coverage limit investors’ ability to apply their net zero commitments to other asset classes.

While the coverage of large companies in developed markets is reasonably good, the research identifies significant gaps in the quality of the data and information being provided. In part, this is a function of the quality and availability of the corporate data that underpins these data products. However, some gaps are attributable to the data products themselves and wider gaps in the marketplace, including: the transparency of the products; a lack of common definitions; limited availability of sector and geographic pathways; and poor coverage and reliability of portfolio-level metrics and methodologies.

What actions can be taken?

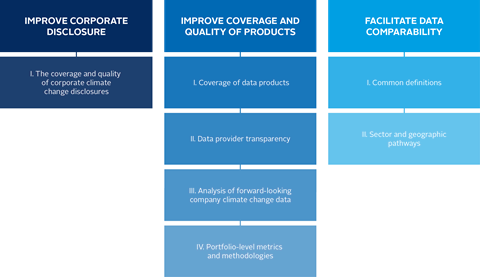

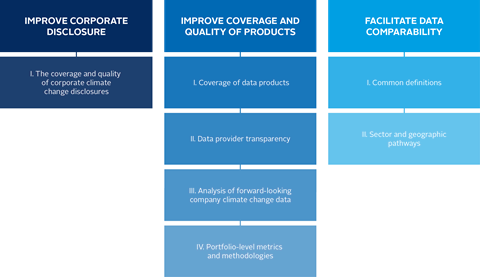

Our research points to a number of general conclusions about how the data ecosystem might be strengthened to better support investors with the delivery of their net zero commitments. Our recommendations are categorised into three overarching areas of the data ecosystem that explain why there is a disconnect between investors’ needs and what the market provides. These areas are then broken down into seven themes.

Figure 1. Summary of recommendations

It will be important for the industry to reflect on these recommendations as it drives towards net zero. Although this report identifies gaps in the market, it also recognises that some of our recommendations are already being addressed by a number of initiatives, such as the Net Zero Financial Service Providers Alliance. In addition, a number of data providers have started to offer or are designing products that respond to these recommendations. While there are clear signs of industry engagement and progress, there remains a pressing need for general agreement, consistent implementation and development of tools and methodologies to meet investors’ data needs to support their net zero commitments.

The following sections summarise the full set of recommendations that have been identified in the research.

Improve corporate disclosure

I. The coverage and quality of corporate climate change disclosures

Standard-setters and regulators should introduce mandatory climate disclosure through regulation for public and private companies. In particular, these rules and laws should require:

- Disclosure of emissions on an ownership (equity) basis, including the following metrics (and targets): Scope 1, 2 and 3 GHG emissions, broken down by type of GHG emission, the proportion of emissions that are verified, an explanation of changes in GHG emissions and climate targets, and the proposed strategy and dependencies to meet the targets.

- Disclosure of industry metrics and corresponding targets for those in the 12 most energy-intensive sectors.

- Publication of transition plans, describing how companies intend to align their business models with net zero by 2050.

Improve coverage and quality of products

I. Coverage of data products

- Data providers should extend their coverage of the investable universe outside of the current focus on listed equities and corporate bonds, and particularly beyond large entities operating in developed markets.

- Where needed, investors, investor-backed net zero initiatives and data providers should work together to develop climate data reporting and assessment methodologies for missing asset classes.

II. Data provider transparency

Data providers should ensure that they:

- Disclose the source(s) of entity-level emissions data and the reporting year to which the emissions relate.

- Provide ownership-based emissions data.

- Disclose the quality of Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions data for each entity in line with a relevant, recognised quality score (e.g., that provided by the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials).

- Disclose the uncertainty in emission estimates.

- Disclose the methodologies used for estimating current and future emissions.

- Disclose the methodologies, data and assumptions used for assessing climate change governance.

- Provide a detailed explanation for company and portfolio alignment assessment methodologies, in particular for implied temperature rise (ITR) metrics.

III. Analysis of forward-looking company climate change data

Data providers should provide products that analyse:

- The credibility of company emission targets, identifying the main factors that will determine whether such targets are likely to be reached.

- The alignment of a company’s strategy (including its capital expenditure) with the company’s emission reduction targets and climate change strategy.

- The abatement cost curves for companies’ emission reduction strategies for Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions.

IV. Portfolio-level metrics and methodologies

Investor-backed net zero frameworks and initiatives, in conjunction with data providers, should:

- Develop methodologies that enable investors to report on portfolio- and/or fund-level real-world emission reductions and net zero alignment.

- Assess the overall uncertainty of portfolios’ emissions, in both absolute and relative (intensity) terms.

- Analyse and report on the reasons underpinning changes in portfolio-level emissions and emission intensities, particularly: (i) changes in company enterprise value, including cash; (ii) new or divested positions; (iii) changes in entity weights; and (iv) changes in absolute emissions.

- Disclose the methodology, scientific basis and uncertainty of investment and portfolio ITR assessments.

- Develop tools to integrate the goal of net zero into strategic asset allocation at the portfolio or fund level.

Facilitate data comparability

I. Common definitions

Investor-backed net zero frameworks and initiatives should:

- Adopt a common definition of alignment for companies and other entities.

- Develop and agree a common approach to assess and report fossil fuel reserves.

- Develop and implement a common set of principles, or definitions, to be used by data providers for identifying climate solutions.

- Engage with data providers to adopt these three definitions, and to ensure that the data and information provided is aligned with these definitions.

II. Sector and geographic pathways

Investor-backed net zero frameworks and initiatives should:

- Agree on a set of principles by which geographic and sector-specific transition pathways are developed.

- Agree on specific geographic and high-impact sector transition pathways.

- Engage with data providers to encourage them to use the specific geographic and high-impact sector transition pathways for assessing company alignment.

1. Introduction

Why is climate data important for net zero?

To meet the goal of the Paris Agreement to halt global warming, trillions of dollars of investment will be required in clean energy, zero-carbon transport, decarbonised industrial processes and climate-friendly agriculture. Institutional investors have a key role to play meeting its goals; they will provide much of the capital to enable the low-carbon transition, they can engage with the companies and other entities in which they invest to reduce their emissions, and they can engage with policy makers to create the policy frameworks and incentives necessary to accelerate decarbonisation. A number of investor-backed net zero frameworks and initiatives have been established to guide and support investors in these efforts.

To make informed investment decisions and to engage effectively with their investments, investors need robust, reliable data about the climate change policies, commitments, practices, processes and performance of their investments. In practice, time and resource constraints mean that investors often rely on third-party data providers[1] to collate, aggregate and check data and to process that data in ways that meet investors’ needs. These data providers, therefore, play an important role in supporting investors’ net zero activities.

The number of organisations providing climate data and related services to investors is proliferating, as is the number of products offered by these organisations. As the market for climate data expands, investors and other stakeholders have highlighted the importance of maintaining the quality of these products, given the role that they can play in decision-making by investors.

About this report

This report aims to help investors and data providers better understand the critical role of climate data and some of the factors that can ensure the market delivers decision-useful data that can adequately support investors’ net zero commitments to real-world emission reductions.[2] Based on desk research and interviews with investors and data providers, it sets out to address the following questions:

- What do investors need to know and, specifically, what data is needed by investors to support their net zero commitments, in particular to reduce emissions in the real world? (Section 2)

- What is the quality and coverage of climate data offered by data providers, and what are the gaps between the data provided and investors’ data needs? (Section 3)

- What actions can be taken by investors, data providers and other stakeholders to build a data ecosystem that provides the data needed by investors to deliver and credibly report on their net zero commitments? (Section 4)

A number of reports have been published describing the landscape of investor-based initiatives and frameworks focused on net zero,[3] and analysing the quality of the data and the products currently offered to the investment market.[4] This report extends and refines this previous work. The research explicitly analysed what investors are looking for, using the requirements of investor initiatives as its basis, against the landscape of available climate data and products, to highlight gaps between these needs and the data that was available at the time of the research.

The research process involved:

- A review of the literature on investor climate data needs.

- Analysis of the requirements of the 17 major investor-led net zero and similar climate change frameworks and initiatives.

- A review of 62 climate data products from 19 data providers, including a feedback stage with the data providers.

- In-depth interviews with 16 institutional investors from across the globe about their climate data needs.

We recognise that the market continues to develop rapidly, with considerable innovation in the data provision space. For example, between the review stage in October 2022 and publication of this report, several new research reports and data products were released. This is why we conducted a further round of engagement with service providers in April and May 2023 to validate our recommendations.

The report is structured as follows:

- Section 2 provides an overview of investor-backed climate change and net zero initiatives and frameworks and of the major regulatory requirements for investors to disclose climate-related information. From this analysis, we derive a list of the data and indicators that investors need to meet these obligations.

- Section 3 critically reviews the climate data that is available from the data providers, examining its coverage, quality and relevance.

- Section 4 presents the main conclusions and offers detailed recommendations for investors, for investor-backed climate change initiatives and for data providers.

- Appendix 1 provides a detailed description of the research approach and Appendix 2 an overview of the investor-backed climate change and net zero initiatives, frameworks, tools and guidance reviewed in this research.

2. What data do investors need to support their net zero commitments?

Our interviews with investors were clear: in the absence of mandatory requirements for investors to commit to net zero emissions, investors’ data needs are primarily defined by the requirements of investor-backed voluntary climate change and net zero initiatives. This section of the report therefore focuses primarily on these initiatives, with a brief comment on mandatory reporting requirements. The research uses this analysis to derive a list of the specific data and indicators that investors need for decision-making and reporting on net zero.

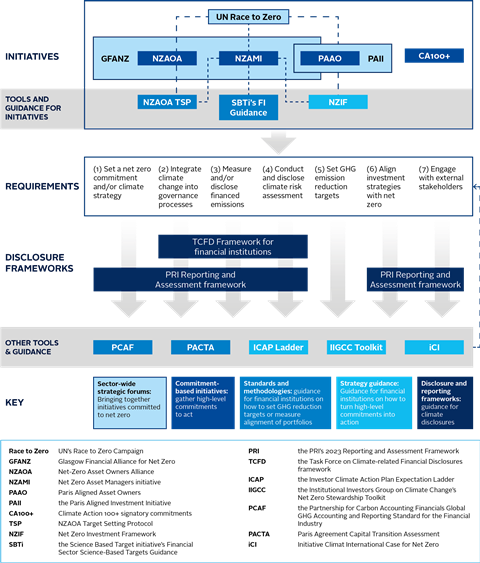

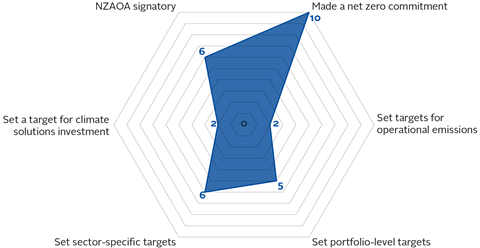

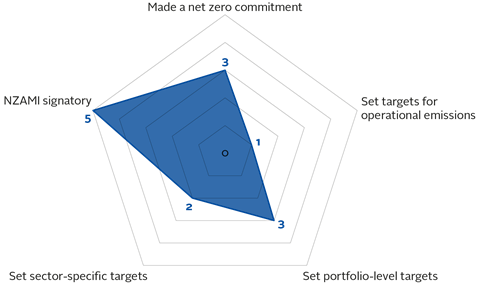

Review of investor-backed climate change and net zero initiatives

The research identified 17 major investor-backed climate change and net zero initiatives (see Appendix 2). These can broadly be categorised as:

- Sector-wide strategic forums that bring together net zero finance initiatives, such as the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ).

- Commitment-based initiatives, such as the Net Zero Asset Owner Alliance (NZAOA).

- Disclosure frameworks, including the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and the PRI’s Reporting and Assessment (R&A) framework.

- Tools and guidance that produce standards and methodologies, such as the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF).

- Strategy guidance, such as the Investor Climate Action Plan (ICAP) Expectations Ladder.

As shown in Figure 2, the initiatives specify requirements in aggregate for their signatories and are sometimes informed by specific guidance documents – such as the NZAOA’s Target Setting Protocol (TSP), which specifies the target-setting requirements for asset owners’ commitments to the NZAOA.[5]

The initiatives agree on many of the actions they expect of investors. In broad terms, they expect investors to:

- Make a high-level board commitment to reduce emissions or reach net zero in their investment portfolios.

- Establish appropriate governance processes for the oversight and implementation of these commitments.

- Measure and report on their financed emissions. This push has been supported by the development of robust guidance on emissions accounting and target setting for financial institutions (e.g., from the PCAF).

- Assess and understand their exposure to climate risk by conducting climate risk assessments (with many identifying scenario analysis as an important tool in this regard).

- Set greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction targets across at least some asset classes. These should focus on real-world emission reductions.[6]

- Align investment strategies with net zero.

- Engage external parties, such as companies, clients and policy makers, to reduce their own emissions and support wider efforts to reduce emissions.

Figure 2 also shows how the initiatives relate to each other, although the delineation and relationships are not always clear cut.[7] The other elements of Figure 2 illustrate the role of:

- Disclosure frameworks: many of the investors’ requirements need to be disclosed against one or more disclosure frameworks.

- Tools and guidance: these help investors meet the requirements of net zero initiatives. In some instances, the tools and guidance could also reinforce these requirements or set specific requirements for investors (e.g., the ICAP Expectation Ladder).

Figure 2. The landscape of investor-backed climate change and net zero initiatives

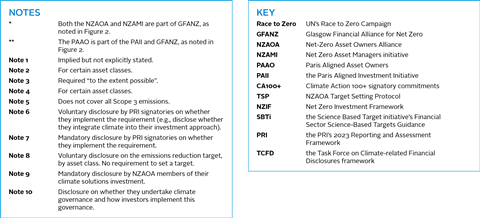

Figure 3 maps the requirements noted in Figure 2 to each initiative, the tools and guidance for initiatives and the disclosure frameworks.[8]

As set out in the figure, there are differences between the initiatives, reflecting their different purposes and objectives, different types of initiatives (e.g., a commitment-based initiative or disclosure and reporting framework) and, in particular, the extent to which they emphasise emissions reductions versus investment risks.[9] The focus on climate change transition by the initiatives is important, as it requires investment and engagement actions to be aimed at reducing emissions in the global economy, rather than just reducing the emissions, or the investment risk, associated with or reported for a portfolio. While divesting from emissions-heavy investments may reduce the emissions intensity of a given portfolio and manage short-term investment risks,[10] it may not be consistent with an initiative’s overarching priorities.

Figure 3. Mapping obligations resulting from the investor-backed climate change and net zero initiatives

|

REQUIREMENT |

Initiatives (linked tool and/or guidance) |

Tools and guidance for initiatives |

Disclosure frameworks |

|||||||

|

Race to Zero |

NZAOA* (TSP) |

NZAMI* (TSP/NZIF/SBTi) |

PAAO** (NZIF) |

CA100+ |

TSP |

NZIF |

SBTi |

PRI |

TCFD |

|

|

(1a) Set and/or disclose a net zero commitment |

(Note 6) |

|||||||||

|

(1b) Set a decarbonisation strategy for portfolio/fund |

||||||||||

|

(2) Integrate climate change into governance processes |

(Note 7) |

(Note 10) |

||||||||

|

(3a) Calculate/disclose Scope 1 and 2 emissions |

(Note 1) |

(Note 2) |

(Note 1) |

(Note 7) |

||||||

|

(3b) Calculate/disclose financed (Scope 3) emissions |

(Note 1) |

(Note 3) |

(Note 1) |

(Note 7) |

||||||

|

(4a) Assess and/or manage climate risk with scenario analysis |

(Note 7) |

|||||||||

|

(4b) Publish TCFD-aligned disclosures |

(Note 7) |

|||||||||

|

(5a) Set a portfolio-wide Scope 1 and 2 emissions target (all asset classes) |

||||||||||

|

(5b) Set a portfolio-wide Scope 3 emissions target (all asset classes) |

(Note 4) |

(Note 5) |

||||||||

|

(5c) Set emissions reduction targets at the asset class level |

(Note 8) |

|||||||||

|

(6a) Integrate climate into investment approach |

(Note 7) |

|||||||||

|

(6b) Conduct portfolio alignment analysis |

||||||||||

|

(6c) Include climate solutions in investment strategy |

(Note 9) |

|||||||||

|

(7a) Engage with companies or disclose engagement activities |

(Note 6) |

|||||||||

|

(7b) Engage with policy makers or disclose advocacy activities |

||||||||||

This report focuses on the information investors need to develop and implement their net zero investment strategies. However, at present, there are no legal requirements in any jurisdiction which require investors to set a net zero strategy; investors’ data needs are primarily driven by the requirements of the investor-backed climate change and net zero initiatives noted above. This includes data needed to meet disclosure requirements, such as the PRI’s R&A Framework and mandatory reporting requirements.

The R&A Framework requires PRI’s asset owner and investment manager signatories to disclose whether they integrate climate change into their policy, governance and investment strategy processes.[11] In addition, specific disclosure requirements on net zero include:

- Disclosure by NZAOA members of their climate change solution investments.[12]

- Voluntary disclosure of net zero targets by PRI signatories in line with reporting requirements for the NZAOA and Net Zero Asset Managers initiative (NZAMI).[13]

While there are no mandatory requirements to develop and implement net zero strategies, there are an increasing number of mandatory disclosure requirements. Box 1 summarises these, which overlap with most of the requirements[14] from the initiatives listed in Figures 2 and 3.

Box 1. Mandatory reporting requirements for investors

While regulatory investor reporting requirements are not explicitly considered in this report, several countries, including Brazil, Canada, the EU, Hong Kong, New Zealand, the US and the UK, have as of 2022 established or proposed climate change disclosure requirements.[15] These regulations focus primarily on investment risk management, with the majority encouraging investors to report in line with the requirements of the TCFD. However, it is worth noting that (a) these mandatory requirements may increase the number of data points to be reported by investors, and (b) the requirement to report creates pressure to reduce reported emissions.

In addition, the development and adoption of sustainable taxonomies have also led to climate disclosure requirements for investors. For example, the EU Taxonomy requires investors (and other financial institutions) to disclose the proportion of underlying investments that are taxonomy-aligned, starting 1 January 2024, initially covering climate change mitigation and adaptation, with other environmental objectives to be introduced.[16] As the Taxonomy’s screening criteria for climate change mitigation are aligned with the EU’s commitment to achieve net zero by 2050, the disclosure provides an indication of the net zero alignment of investors’ portfolios.We discuss the quality of corporate climate data that underpins investors’ reporting in more detail in Section 3, but it is worth noting that corporate reporting requirements between jurisdictions can be inconsistent and may limit investors’ ability to compare companies across jurisdictions.

Investors’ climate data needs

We now look at the question of what data investors need to meet the requirements of the various investor-backed initiatives. Our research – the analysis of the initiatives, backed up by interviews with investors – suggests that investors want to answer four questions:

- To what extent are individual investments (e.g., companies) aligned with net zero goals? To assess this question, investors need information on current emissions, current exposures to opportunities (e.g., climate solutions) and to risks (e.g., fossil fuels), the actions being taken to deliver real-world emission reductions, and the quality of an investment’s climate change governance.

- To what extent will individual investments be aligned with net zero goals in the future? Here, investors need information on future emission trajectories, emission targets and the alignment of the investment’s strategy with the goal of delivering real-world emission reductions.

- Is the current position of their portfolios and funds aligned with their net zero goals (i.e., in aggregate, are their investments net zero-aligned)?

- What level of emissions reductions are required over time for their portfolios and funds to become net zero-aligned? Investors generally use net zero emission pathways to conduct these assessments.

Figure 4 maps the framework requirements presented in Figure 3 against the four questions (or categories of data needs) above, identifying the data needed by investors to address these questions. As can be seen, some of the needs are climate data points (e.g., current and projected future Scope 1 and 2 emissions), others are derived data points (which combine climate data points with operational performance, such as measures of emissions intensity, where climate data is normalised by measures of corporate activity) and others are tools (which generally use climate and derived data points as inputs). In particular, it highlights that climate change-related information is underpinned by corporate climate change disclosure.

Not all of the framework requirements in Figure 4 require climate data. Examples include the requirement for investors to set and publish a net zero commitment, and the requirement to integrate climate change into their governance processes. However, even in these requirements, climate data is often an important input into the decisions made or actions taken and is then needed to effectively track the actions over time.

Figure 4. Information required to assess assets and portfolios against the requirements of investor-backed climate change and net zero initiatives

|

FRAMEWORK REQUIREMENT |

Investment’s current climate change position related data |

Investment’s forward-looking climate change position related data |

Portfolio’s net zero position related data |

Pathway and other data requirements |

||||||||||||||

| Investment’s Scope 1 & 2 emissions data | Investment’s Scope 3 emissions data | Investment’s fossil fuel exposure | Investment’s quality of climate change governance | Investment’s exposure to climate solutions | Investment’s reduction target (short, medium or long term) | Investment’s scenario analysis | Investment’s future emission estimates | Company’s (climate change) strategy and strategy alignment | Portfolio’s emissions / emissions intensity | Portfolio’s future emission estimates | Portfolio’s net zero target alignment | Portfolio’s climate solutions exposure | Portfolio’s scenario analysis | SAA climate change tools | Sector-specific and geography-specific net zero pathways | Sector-specific scenario data | Geography-specific scenario data | |

|

(1a) Set and/or disclose a net zero commitment |

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

(1b) Set a decarbonisation strategy for portfolio/fund |

✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||||||||

|

(2) Integrate climate change into governance processes |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

(3a) Calculate/disclose Scope 1 and 2 emissions |

✔ |

|

|

|

✔ |

|

||||||||||||

|

(3b) Calculate/disclose financed (Scope 3) emissions |

✔ |

|

|

|

✔ |

|

||||||||||||

|

(4a) Assess and/or manage climate risk with scenario analysis |

✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

✔ |

|||||

|

(4b) Publish TCFD-aligned disclosures |

✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||

|

(5a) Set a portfolio-wide Scope 1 and 2 emissions target (all asset classes) |

✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

|

(5b) Set a portfolio-wide Scope 3 emissions target (all asset classes) |

✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||

|

(5c) Set emissions reduction targets at the asset class level |

✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

|

✔ | |||||||||||

|

(6a) Integrate climate into investment approach |

✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

|

(6b) Conduct portfolio alignment analysis |

✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

|

(6c) Include climate solutions in investment strategy |

✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

|

(7a) Engage with companies or disclose engagement activities |

✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

|

✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||

|

(7b) Engage with policy makers or disclose advocacy activities |

✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||||||

3. What is the coverage and quality of climate data?

Our research examined 62 climate data products from 19 data providers.[17] This section provides an assessment of the climate data and climate data provision from these products and providers against the climate data needs defined in Section 2.

The assessment identifies a number of issues with climate data, which cut across all four of the categories of climate data needs. These fall into seven key themes:

- Coverage and quality of corporate climate change disclosures

- Coverage of data products

- Data provider transparency

- Analysis of forward-looking company climate change data

- Portfolio-level metrics and methodologies

- Common definitions

- Sector and geographic pathways

Coverage and quality of corporate climate change disclosures

As discussed in Section 2, climate change-related information provided by companies underpins the majority of the data products that are currently offered to investors. This means that the quality of corporate disclosures is the key influence on the quality of the data provided to investors.

Our review of the literature and our discussions with investors and data providers suggest that there are significant limitations in the data being provided by companies, and therefore what data providers can make available to investors.

Issue 1: Incomplete emissions data

While company disclosure rates have improved, many companies still do not publicly report their emissions. For example, fewer than half of the companies in the MSCI ACWI broad global market index[18] publicly disclose their emissions (see Figure 5).

Figure 5 also shows that the disclosure rates for Scope 3 emissions remain significantly lower than for Scope 1 and 2 emissions. This is important given that, in many sectors and companies, Scope 3 emissions are many times larger than Scope 1 and 2 emissions.[19] Even where Scope 3 emissions are reported, investors raised concerns about the reported numbers, questioning whether all material category Scope 3 emissions were reported, and expressing concerns about a lack of transparency regarding the methodologies used by companies to estimate Scope 3 emissions and regarding boundaries, i.e., how far up or down the value chain they were set.

Figure 5. GHG disclosure rates for MSCI ACWI IMI constituents, 2017 to 2022[20]

![]()

In particular, investors highlighted the need for sector-specific emissions data for the 12 most energy-intensive sectors,[21] which should include Scope 1, Scope 2 and significant Scope 3 emissions, capturing both current and forward-looking data, and broken down (at 5- and 10-year intervals). In line with the sector-specific requirements, investors have also asked that emissions should be broken down by type of GHG, particularly for methane.[22]

Issue 2: Emissions reporting boundaries not aligned with investors’ data needs

Investors need data that reflects their financial exposure to an asset; that is, reporting boundaries should be aligned with the financial accounts of the company. In the case of listed equities, investors need companies to disclose emissions on an equity (or ownership) basis[23] to enable them to correctly assess climate change-related investment risk, and to correctly account for their exposure to real-world emission reductions. Our interviews with investors and our review of CDP emissions data and corporate sustainability reports suggests that, in practice, many companies still only report on an operational control basis. This means that their reporting is not aligned with the financial accounts.

While the main conclusion is that companies should report on an ownership basis, it is important to acknowledge that investors are also often interested in assets or investments where the company has operational control (e.g., joint venture mining companies). Therefore, companies should also – where relevant – consider reporting emissions based on operational control, but this reporting should be additional to and not replace ownership-basis reporting.

Investor interviewees also raised specific concerns about the lack of clarity in the climate reporting of companies with complex corporate structures, and the frequent lack of clarity about the corporate or organisational boundaries used in reporting by companies.

Issue 3: Lack of verification of reported data

Ideally, investors would like data to be verified, as this would give them greater confidence in the numbers being reported by companies. However, at present, most reported climate data is not independently verified. This is an evolving area, with companies experimenting with different models of data verification and with regulators considering whether mandatory data verification requirements should be introduced.[24]

Issue 4: Companies do not explain why reported emissions have changed over time

Company emissions can change year-on-year for a variety of reasons: the company’s own emission reduction and energy saving efforts; changes in the emissions intensity of the electricity grid; changes in production or activity levels; acquisitions or divestments; and changes in the manner in which emissions are calculated and reported (e.g., changes in the reporting scope or boundaries used, changes in assumptions, or changes in emission factors). Some of these may result in changes in real-world – or actual – changes in emissions (e.g., energy saving, changes in business activity, changes in grid electricity carbon intensity), and some may simply be accounting changes (e.g., changes to the scope of reporting). Furthermore, some may be a result of direct, purposive action by the company, whereas others (e.g., changes in the energy mix of the electricity grid) may be outside the company’s influence.

Investors need to understand the factors that drive changes in reported emissions, and companies should explain the contribution and actions that they and others have taken to affect reported emissions.

Issue 5: Companies do not adequately specify their emission reduction targets

Target-setting is complex. Companies need to set targets that are relevant to their business and to their contribution to the goal of net zero. Having said that, investor interviewees stressed that it is often difficult to make a robust assessment of the credibility of a company’s climate change targets. Among the issues identified were a lack of clarity around the future trajectory of emissions from the company (e.g., how short-, medium- and long-term targets fit together), and around the proportion of Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions covered by the targets. Companies also need to articulate their proposed strategies to meet their targets, including setting out their capital requirements, research undertaken, the underlying assumptions on legislation, technology and markets, actions to be taken, and the costs and benefits associated with these actions.

These insights are in line with the recommendations of the UN’s High-level Expert Group (HLEG) on net zero emissions commitments for non-state actors[25] and the NZAOA statement on the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) exposure draft.[26] The HLEG report asks companies to: (i) report separate targets for material non-CO2 GHG emissions; (ii) include emissions across their full value chain and activities; and (iii) separate out embedded emissions within fossil fuel reserves, as well as any land use-related emissions and risk-adjusted sequestration in biomass. Similarly, the NZAOA statement specifies that strategies to meet targets should require companies to “pivot towards a net zero future with near-term (every five years) science-based targets consistent with the long-term objective of net zero by 2050”.

Ultimately, a company’s reduction targets should be reported in its transition plan. A number of initiatives have already looked to define what a ‘credible’ transition plan should include (see Box 2). In addition to the points noted above on target setting, they identify requirements or recommendations on other issues, such as verification/audit and sectoral and geographic pathways. As the recommendations from these initiatives are relatively new,[27] defining ‘credible’ corporate transition plans remains a work in progress.

Box 2. Defining credibility in transition plans

A number of initiatives have attempted to define what transition plans should cover to be considered credible. They include:

- NZAOA, which defined a credible plan in Annex 1 of its statement on the ISSB exposure draft.[28]

- UN HLEG, which recommended what a company’s transition plan must include.[29]

- The Transition Plan Taskforce (TPT), launched by the UK government in 2022, developed a draft gold standard for private sector climate transition plans in November 2022, which sets out a comprehensive list of disclosure requirements.

- GFANZ, which published its Expectations for Real-economy Transition Plans[30] report in September 2022. It specifies the components of transition plans (i.e., disclosure requirements) that financial institutions will be looking for.[31]

In addition, some regulators are working to define what they expect from transition plans. For example, in addition to the TPT, the European Commission has published its final European Sustainability Reporting Standard on climate change (ESRS E1), which sets out requirements under the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). This includes disclosure requirements for a transition plan for climate change mitigation (E1-1).

Issue 6: Company data is often out of date

Investors would also like more up-to-date information about emissions and performance, with many commenting that company data is generally backward-looking (referring to the previous 12 months), and often released three months after the end of the reporting period. Interviewees acknowledged that this is not an easy issue to fix, given the need to quality-assure the data, and acknowledged that time is also required by data providers to incorporate new information into their products.

To address the issues listed above, investors need access to high-quality climate-related corporate sustainability disclosure. Standards, rules and laws play an important role in requiring high-quality climate-related disclosure from companies; these have been increasing at both global and regional levels, as set out in Box 3.

Box 3. The changing landscape of climate-related corporate data

Companies are increasingly required to report on their emissions. The current mandatory corporate climate reporting requirements can be divided into disclosure of: (1) emissions (although usually limited to Scope 1 and 2 emissions), (2) TCFD-aligned reports and, albeit limited to the EU, (3) the proportion of turnover and investments aligned with national or regional “green taxonomy” requirements relating to climate change.

There were major developments in climate reporting in 2022, which will expand the coverage and standardisation of current corporate reporting. At the global level, the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) Foundation’s ISSB consulted on its exposure draft standards (the ISSB EDs), which are intended to provide a global baseline for climate-related financial disclosures, subject to jurisdictional-level adoption. At a regional level, the US Securities and Exchange Commission consulted on its Proposed Rule, which contains mandatory climate reporting requirements for listed companies, while the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group consulted on its European Sustainability Reporting Standards Exposure Drafts (ESRS EDs), which will constitute reporting requirements under the CSRD. The ISSB has now released its final standards and the final ESRS have now been released.

In addition, initiatives are also looking to improve the accessibility of this corporate data for investors (and other stakeholders). In particular, plans to create a Net-Zero Data Public Utility (NZDPU) were announced in 2022 by the Climate Data Steering Committee to address data gaps, inconsistencies and accessibility, with an initial focus on company and financial institution-level data for emissions and reporting of net zero targets (see Recommendations for the Development of the Net-Zero Data Public Utility).[32] The Committee is not a standard setter, but will align with the aforementioned standards, rules and laws. More details on the NZDPU’s exact scope of work and work programme is still pending at the time of this report.

Similarly, the European Commission proposed a European Single Access Point in 2021 to “offer a single access point for public financial and sustainability-related information about EU companies and EU investment products”.[33] In principle, this would provide investors with access to data and information reported by companies under the EU’s CSRD, although the specifics of the initiative remain under debate at the start of 2023.

Coverage of data products

Coverage is measured using the number of providers servicing the asset class or offering the data point, which we recognise as a proxy for the breadth of coverage. Overall, our review of data providers identifies three limitations in climate data coverage.

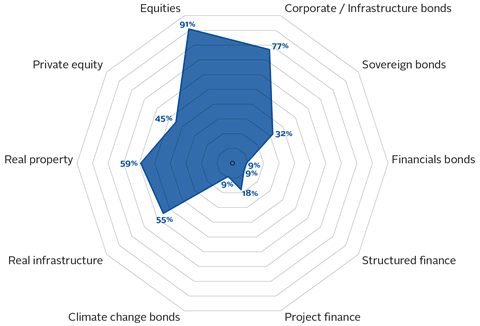

Issue 1: Limited coverage in asset classes outside listed equities and fixed income

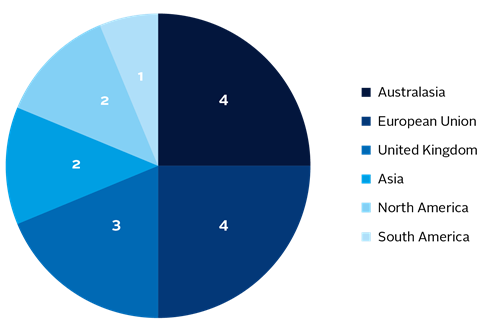

Listed equities and corporate bonds are the asset classes with the greatest coverage, in terms of the number of providers reviewed that focused on them. Real infrastructure and property are also reasonably well covered, with two providers offering products focusing on them. Other asset classes have not received the same level of attention. This is illustrated in Figure 6, which summarises the percentage of providers reviewed that cover different asset classes. (It is important to note that some providers address more than one asset class.)

Figure 6. Percentage of the providers reviewed servicing each asset class

The focus on listed equities, corporate bonds, property and infrastructure reflects the quality of corporate climate change disclosure in these asset classes and the fact that there are now recognised assessment methodologies for them.[34]

The relatively good coverage of listed equities and fixed income, and the less comprehensive coverage of other asset classes, was confirmed by investors interviewed for this project. Most, particularly those based in Europe, felt that they had sufficient data for listed equities and corporate bonds to begin tangibly incorporating these two asset classes into their net zero strategies. Many had already set or were in the process of setting short-, medium- or long-term Scope 1 and 2 emission targets for their developed market portfolios in these asset classes.

A number of investors have started implementing their commitments in other classes, particularly infrastructure and real estate (in line with the availability of products), but the lack of data is delaying progress. Interviewees confirmed that they generally prefer to wait for data to become available before making commitments in specific asset classes. Many were optimistic that the coverage of data will improve over time as methodologies are developed and adopted, as companies and other entities provide more information on their emissions and on their activities, and as data providers integrate this data into their products. For example, the Assessing Sovereign Climate-related Opportunities and Risks (ASCOR) Project[35] is developing an assessment framework for sovereign bonds.

Issue 2: Geographic and size biases

There are strong geographic and size biases in the products that are available for equities and fixed income. Most data providers have good coverage of large companies and of developed markets. However, emerging markets and smaller companies are less well covered, both in terms of the number of companies covered and the number of metrics or data points provided.

Some initiatives are beginning to address this issue. For example, the UN HLEG has recommended that “[n]on-state actors should build support to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and micro enterprises in their efforts to decarbonise and green their business.”[36] It specifically recommended that the Net Zero Financial Service Providers Alliance (NZFSPA)[37] commits “to support SMEs, and other non-state actors in developing countries with limited resources, to develop high‑quality data and have their net zero pledges and transition plans verified”.[38] The NZFSPA is set to consider this recommendation.

Issue 3: Gaps in products on strategic asset allocation

For listed equities and bonds, there is reasonable provision of data across most of the areas identified in Figure 3, with at least a quarter of the data providers reviewed offering data or other services in each area. However, very few data providers offer strategic asset allocation (SAA) tools. These are important for activities such as developing a decarbonisation strategy, integrating climate change into investment analysis and setting targets relating to climate solutions.

The following sections focus on different aspects regarding the quality of climate data products. As the availability of data is a prerequisite to assess quality, the focus of the remaining thematic areas is on listed equities and corporate bonds.

Data provider transparency

Different data providers often provide materially different climate data for the same entity. Investor interviewees were clear that the lack of transparency about data sources and calculation methodologies limits their ability to use the data being provided.

The research identifies the following areas where transparency is especially lacking.

Issue 1: The source, quality and relevance of underlying emissions data

Investor interviewees said they need to understand how reported emissions have been calculated or produced. The limited transparency on emissions starts with the transparency around the corporate data (as discussed above), including how companies have calculated or estimated their emissions. This data is then processed and disseminated by data providers.

The investor interviewees were clear that data providers need to provide more comprehensive information alongside the reported emissions numbers. As a minimum, this should include: the source of the information; the year the information relates to; the reporting basis (i.e., whether equity or operational control); whether the company emissions data is verified; and, if relevant, the calculation methodology used by the company, including relevant assumptions and emissions factors (see below).

Data providers are responding to these expectations. Many of those reviewed for this research do – for at least some products – identify sources and years for company emissions data, although there tends to be limited transparency on whether emissions are on an operational or ownership basis. However, where there are significant data gaps, data providers often provide emissions estimates to compensate.

However, many of the investors interviewed expressed concern about the data being produced in this way, commenting that data providers are not particularly transparent about how they generate these estimates (e.g., around the methodologies, assumptions and emission factors used) or (where relevant) about how they assess portfolio alignment. This is not to say that reported data is necessarily better than estimated data from data providers in all instances, particularly as company reporting may similarly be reliant on estimation methods.

Those investors that use more than one data provider need those providers to disclose the methodologies used to understand why estimated emissions differ between providers. As Box 4 indicates, there are various reasons why different providers may produce different emissions data.

Box 4. Some reasons for differing emissions estimates

Emissions estimates for the same entity may differ between data providers because of:

- The basis for the emission factors (e.g., whether based on revenue or financial metrics, or on underlying activity).

- The granularity of the emission calculation process (e.g., where emissions are estimated site by site, at a divisional level, or at the parent company level).

- The relevance of the emission correlation to the entity in question (e.g., whether an appropriate peer group – in terms of geography or underlying activities – was used to develop the emission estimation correlation).

- How often the methodology and correlations are updated, and whether they represent the most recently available data.

- The extent to which companies’ own data is used (and the quality of that data relative to the calculated data).

- For Scope 2 – electricity consumption – emission estimates, the extent to which location-specific and fuel-specific emission factors are used.

- Quality control processes within the data provider.

Some data providers have responded to demands from investors for the calculation methodology by using a data quality score. An example of this is provided in Box 5.

Box 5. The PCAF Data Quality Score for listed equities and corporate bonds

The Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF) has developed a ranking of the quality of reported emissions for listed equities and corporate bonds. As set out below, the ranking provides a potential model for data providers to communicate the quality of their data to investors.

| Data Quality | Options to estimate the financed emissions | When to use each option | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Score 1 | Option 1: Reported emissions | 1a | Outstanding amount in the company and EVIC are known. Verified emissions of the company are available. |

| Score 2 | 1b | Outstanding amount in the company and EVIC are known. Unverified emissions of the company are available. | |

| Option 2: Physical activity-based emissions | 2a | Outstanding amount in the company and EVIC are known. Reported company emissions are not known. Emissions are calculated using primary physical activity data of the company’s energy consumption and emission factors70 specific to that primary data. Relevant process emissions are added. |

|

| Score 3 | 2b | Outstanding amount in the company and EVIC are known. Reported company emissions are not known. Emissions are calculated using primary physical activity data of the company’s production and emission factors specific to that primary data. | |

| Score 4 | Option 3: Economic activity-based emissions | 3a | Outstanding amount in the company, EVIC, and the company’s revenue are known. Emission factors for the sector per unit of revenue are known (e.g., tCO2 e per euro or dollar of revenue earned in a sector) |

| Score 5 | |||

| 3b | Outstanding amount in the company is known. Emission factors for the sector per unit of asset (e.g., tCO2 e per euro or dollar of asset in a sector) are known. | ||

| 3c | Outstanding amount in the company is known. Emission factors for the sector per unit of revenue (e.g., tCO2 e per euro or dollar of revenue earned in a sector) and asset turnover ratios for the sector are known. | ||

Source: PCAF (2022), The Global GHG Accounting and Reporting Standard Part A: Financed Emissions Second Edition.

It is important to stress that data quality scores, such as those presented in Box 5, do not address all of the concerns of investors, as these scores tend to focus on addressing the gaps in calculation methodologies used by the company or data provider. As a result, they do not provide a strong indicator of estimation uncertainty.[39] For example, a verified emission number provided by the company (Option 1a) may be subject to significant monitoring uncertainty, whereas emissions estimates based on Option 2a could have a high degree of certainty. Similarly, it is important to recognise limitations to the scope of these quality scores, compared with the breadth of investors’ portfolios. For example, the PCAF only specifies detailed data quality score tables for seven specific asset classes.[40]

Issue 2: The uncertainties in climate data

In practice, while emission estimates may be useful to help investors identify which companies may be the largest emitters and, hence, should be the focus of engagement, the uncertainties in emission estimation means that such data is generally of limited value when assessing the emission abatement activities of a company or in distinguishing between different companies based on their emission reduction performance.

One key data point that would give investors quantitative insights on emissions data is the error range of the emissions estimate. However, none of the data providers reviewed reported publicly on these error ranges.

Alternatively, a qualitative approach to addressing the uncertainty in climate data would be to use the data quality scores (above) as a proxy. However, such a proxy would be imperfect, as a high data quality score does not necessarily mean that the data is more certain. Instead, investors must consider such scores in conjunction with a wider explanation of the data.

Issue 3: The methodologies used to develop climate products

Here, interviewees particularly highlighted that the methodologies for implied temperature rise (ITR) metrics for companies and qualitative assessments of climate change governance are unclear.

A number of interviewees noted that the utility of ITR metrics as a decision-making tool is questionable. This is due to the lack of transparency in their underlying methodologies as well as the wide variations in company temperature scores generated by different providers, due to the lack of common methodologies. However, there is significant work underway to improve the robustness of ITR methodologies and the usefulness of ITR metrics to investors.[41]

Some data providers provide qualitative assessments of climate change governance, usually presented as an overall climate change governance score. Typically, these focus on an assessment of the process of managing climate change, i.e., around corporate governance of climate change, such as who is responsible for climate change, their role and skill set, and reporting structures. However, mirroring the comments made about emissions data, interviewees noted that the methods used (e.g., the factors considered and the weights given to different aspects of governance[42]) are seldom made publicly available. This means it is not possible to understand the reasons why providers offer different assessments of companies on this issue.

Overall, broader regulatory developments are underway, aimed at improving transparency of the methodologies used by ESG data products. See Box 6 for an overview.

Box 6. Recent regulatory developments on ESG data and ratings products

The following regulatory developments are all centred around improving the transparency of ESG data and ratings products, as well as the governance of their providers, building on recommendations from the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO):

- IOSCO recommendations – in 2021, IOSCO called for oversight of providers and published a set of recommendations for regulators in its Final Report on ESG Ratings and data products providers.

- Japanese Code of Conduct – in 2022, the Japanese Financial Services Agency released a voluntary Code of Conduct for ESG Evaluation and Data Providers.

- Indian consultation – in February 2023, the Securities and Exchange Board of India published a Consultation Paper to gather feedback on a proposed regulatory framework, which includes proposals for ESG ratings providers.

- UK Code of Conduct – in July 2023, the ESG Data and Ratings Working Group, which was established by the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority, opened a consultation on its voluntary code of conduct.[43] The UK government’s Treasury has also announced its intention to regulate ESG ratings providers, and was consulting on a proposed regulatory regime until June 2023.

- EU regulation – in summer 2023, the European Commission also came forward with a legislative proposal to regulate ESG ratings providers.[44] This follows an initial consultation on the functioning of the ESG ratings market in the EU[45] and a call for evidence by the European Securities and Markets Authority.[46]

Analysis of forward-looking company climate change data

Carbon performance metrics like carbon footprints are generally insufficient to allow investors to determine whether or not a given company is on a credible decarbonisation path. Investors need information on forward-looking targets, and analysis of the credibility of these targets, the adequacy of the company’s climate strategy and the extent to which the climate strategy and climate-related capital expenditure plans are aligned with the company’s overall strategy and capital expenditure plans.[47] Some disclosure requirements have started to ask companies to disclose their capital expenditure against climate goals – see Box 7.

Box 7. Corporate disclosure and the EU Taxonomy

Under the EU Taxonomy, all non-financial corporates are required as of 1 January 2023 to disclose the proportion of their turnover, capital expenditure and operational expenditure that is associated with economic activities that meet the Taxonomy’s screening criteria for climate change mitigation and adaptation. As the Taxonomy defines criteria for economic activities that are aligned with a net zero trajectory by 2050, this disclosure provides a measure of a company’s contribution to the EU’s climate goals. Thereby, it gives investors a proxy for the credibility of companies’ climate strategies in the context of these climate goals.

Several of the investors interviewed said that climate data providers do not adequately address forward-looking company climate change data. Some data providers, typically those focusing on companies in high-emitting sectors, do provide information on company emission reduction targets and on whether corporate strategy and capital expenditure are either aligned with emission reduction targets or with achieving overall climate change goals. However, few data providers currently offer views on whether a company’s targets are achievable or on the dependency of the targets on other factors (e.g., policy interventions or the development of new technologies). Feedback from investors indicated that this would not necessarily require any new corporate disclosures but would rely on data providers using currently available information to produce an opinion on a company’s targets.

Portfolio-level metrics and methodologies

Issue 1: Quality and uncertainty of portfolio-level emissions data

As discussed above, there are significant gaps and uncertainties in the climate data provided to investors. Investor concerns about data quality and uncertainty equally apply where this data is aggregated up to portfolio level; it cannot be assumed that the data uncertainties cancel each other out and it cannot be assumed that comparisons between companies are reliable. In turn, this means that investors need to be careful when making decisions about which companies to invest in or when assessing the overall exposure of their portfolios to climate change-related risks and opportunities.

Looking at the two approaches noted above:

- Qualitative: Several providers have tried to address these issues by providing information on the number of companies, or the proportion of emissions in a portfolio/index, either where emissions have been estimated or conversely have been verified. Some data providers have gone as far as applying the PCAF quality score to some of the major global listed benchmarks.

- Quantitative: The research has not been able to identify any data providers who undertake a quantitative assessment of the overall uncertainty of portfolio emissions, in both absolute and relative (intensity) terms. Note, it is important to have both absolute and relative figures, as there are uncertainties to both metrics.

Issue 2: Real-world emissions reductions

The emissions of a portfolio or benchmark can change year on year for a variety of reasons, including: changes in company enterprise value, including cash (EVIC);[48] changes in the companies in the portfolio or benchmark; the weight of companies in a portfolio or benchmark; and the emissions associated with the companies in the portfolio or benchmark.

Investors need to understand the factors that can drive changes in reported emissions. They should be able to explain changes that are due to actions taken by the entities in the portfolio and those that are due to changes in portfolio weightings; it cannot be assumed that changes in benchmark or portfolio emissions intensity reflect a decrease in real-world emissions.

At present, data providers do not provide information on the drivers of changes in portfolio-related emissions.[49] Investor interviewees noted that this limits investors’ ability to understand the most effective drivers of decarbonisation in their portfolios, and the role played by companies’ own emission reduction and energy saving efforts. Some interviewees also said that growing concerns about greenwashing, combined with this lack of information on the drivers of change in reported emissions, have made them reluctant to make net zero commitments.

A number of data providers now offer equity and corporate bond Paris-aligned or climate change portfolios or benchmarks that are based on emissions-intensity metrics.[50] However, these portfolios and benchmarks differ significantly; for example, some consider only Scope 1 and 2 emissions, whereas others include all three scopes; some exclude certain fossil fuels whereas others have no explicit exclusions; some include climate change governance whereas others do not; some include climate solutions whereas others do not. The consequence is that it is not easy for investors to compare these portfolios or benchmarks or to tell what the drivers of the (aggregate) reported changes in emissions are and, specifically, whether they are as a result of companies actually taking action to reduce their emissions.

Ultimately, however, the economy-wide transition cannot occur unless companies reduce their emissions (i.e., emission reductions must occur in the real economy), and investors should be wary of chasing reductions in portfolio emissions intensity that do not deliver reductions in emissions across the economy.[51]

Issue 3: Reliability and clarity of portfolio alignment metrics

Approximately half of the data providers reviewed undertook aggregation of emissions up to the portfolio level and provide both total emissions and portfolio emissions intensity metrics. However, fewer than half of these appear to produce this analysis of financed emissions that reflects the capital structure of the company.[52] Similar to the commentary on company emissions, a number of data providers reviewed still appear to favour revenue-based intensity metrics and do not consider the capital structure of the company. In addition, calculated revenue-based emission intensities for different portfolios are not comparable, nor can they be easily aggregated to the fund level.

A number of data providers now produce ITR metrics for portfolios. These metrics are designed to allow investors to communicate the degree of portfolio alignment with the objectives of the Paris Agreement. A number of the investors interviewed for this research questioned how decision-useful the metric was, arguing that a balanced and complete portfolio alignment disclosure should not be reduced to a single figure and, if a single figure is to be used, then it should be accompanied by an explicit quantified uncertainty range.

As with ITRs for companies (see above), there was a general lack of transparency around the methodologies being used for assessing the ITR for a portfolio and, even where methodologies are published, interviewees questioned the scientific robustness of the methods being used. They questioned: the basis for aggregating individual company ITRs;[53] whether the aggregation process recognises the need for specific geographic and sector alignment assessment of companies; and whether an ITR metric provides insights into the drivers of change within a portfolio (or of the investor’s contribution to these changes). Interviewees also noted that there is wide variation in the portfolio temperature scores provided by different providers and that there is very limited information available from providers about the reliability of these scores or of the uncertainties associated with them.

These insights from our research are in line with wider commentary that has been raised on ITRs (at both the company and portfolio level).[54] For example, the PRI’s 2021 discussion paper, Forward Looking Climate Metrics, recognised a number of these concerns and, in addition, noted that portfolio-level measures of ITR do not account for indirect systemic risks from climate change. Ultimately, this feedback from the market led to the TCFD describing ITR as “complex and opaque regarding influence of key assumptions”.[55] Box 8 discusses some of the wider factors influencing the development of ITR metrics.

Box 8. Factors influencing the development of ITR metrics

Demand for ITR metrics has been stimulated by:

- Voluntary frameworks and guidance, such as the Portfolio Alignment Team report, which recognises ITR as one of three types of portfolio alignment tools.

- Regulators, like those in the UK’s Department of Work and Pensions, recognising ITR as one possible way that relevant trustees in the UK could measure and report on their investment portfolios’ Paris alignment. Similarly, in its Policy Statement PS21/24, the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority asks asset managers to, as far as is practicable, produce product-level TCFD reports with an ITR metric.

Data providers are not the only organisations looking to develop and to support the application of ITR methodologies. For example, in November 2022, GFANZ released its Measuring Portfolio Alignment report, which sets out guidance on how ITR metrics should be calculated.

Issue 4: Coverage and quality of strategic asset allocation tools

For many investors, their approach to strategic asset allocation (SAA) will play an important role in their climate change strategy, and in particular their investments in climate solutions, infrastructure-type assets and developing countries. In principle at least, SAA processes can explicitly incorporate net zero objectives.[56] However, as discussed under ‘Data coverage’ (see Issue 3: Gaps in products on strategic asset allocation), the tools to incorporate net zero goals into SAA (for equities and fixed income) remain relatively underdeveloped.

Common definitions

Many of the investor interviewees said that inconsistencies in definitions directly contribute to the inconsistencies seen in the climate data that is available to investors. While interviewees expressed caution about over-prescriptive definitions and about stifling innovation, they pointed to three areas where common definitions – supported by investors and adopted by data providers – would be particularly helpful.

Issue 1: Definition of alignment

Some interviewees use external definitions of alignment (e.g., that provided by the IIGCC’s Net Zero Implementation Framework[57]) whereas others have developed their own criteria to assess alignment. As a result, there is no consensus on the scope of alignment (e.g., some use Scope 1 and 2 emissions, others use Scopes 1, 2 and 3) and on the contribution that offsets and nature-based solutions can make to the wider goal of achieving net zero. The consequence is that investors are using different tools and metrics and making different demands of data providers.

Using different definitions of alignment is also an issue among data providers. It means that different data providers can draw different conclusions about the alignment of a specific portfolio. However, more definitive commentary is not possible, as the use of the term within methodologies is difficult to assess using publicly available materials. (See comments above on the lack of transparency around data providers’ methodologies.)

Issue 2: Definition of fossil fuel reserves

Data providers have good coverage of fossil fuel exposure, of current fossil fuel production and of downstream Scope 3 emissions, and these are assessed reasonably consistently across the industry. However, there is limited consistency in how fossil fuel reserves are assessed or reported. One indicator that interviewees broadly agreed the investment industry could use was proven and probable reserves, or 3P (i.e., proven, probable and possible) reserves.[58]

Issue 3: Definition of climate solutions

Different providers define climate solutions in different ways. Many do not publicly disclose the definitions that they use for identifying climate solutions, nor do they explain how their definitions compare to frameworks such as the EU Taxonomy. Initiatives like the NZAOA and groups like GFANZ have started to look to define this term (see Box 9), but these definitions have not yet been adopted universally.

Box 9. Defining climate solutions

The NZAOA’s Target Setting Protocol (3rd edition, Jan 2023) defines “climate solution investments” as “investments in economic activities considered to contribute to climate change mitigation (including transition enabling) and adaptation, in alignment with existing climate-related sustainability taxonomies and other generally acknowledged climate-related frameworks.” This was developed by taking into account publicly available definitions, to improve consistency across the Alliance’s membership in assessing climate solutions.

In its Recommendations and Guidance on Financial Institution Net-zero Transition Plans, GFANZ defines climate solutions as: “Technologies, services, tools, or social and behavioural changes that directly contribute to the elimination, removal, or reduction of real-economy GHG emissions or that directly support the expansion of these solutions. These solutions include scaling up zero-carbon alternatives to high-emitting activities – a prerequisite to phasing out high emitting assets – as well as nature-based solutions and carbon removal technologies.”

Sector and geographic pathways

When assessing company performance against net zero by 2050, investors generally need to look beyond global science-based pathways (or broad-brush assessments of the rate of decarbonisation required) and look at sector- and geography-specific transition pathways. The importance of these pathways was particularly emphasised by investor interviewees in the context of developing countries or emerging markets, where nationally determined contributions (NDCs) define the country’s net zero trajectory.[59]

However, further work is needed to develop these country- and sector-specific pathways and to make them widely available to the investment community. Interviewees suggested that investors should work with global sector representatives or industry transition pathway initiatives to develop these pathways. Interviewees said their development should be underpinned by an agreed set of principles, including a just transition, and the recognition of country- and sector-specific technology development pathways.[60]

While there are initiatives that are working on sectoral decarbonisation pathways (Box 10), their focus has been on benchmarks for high-emitting sectors (with the Transition Pathway Initiative) and on high-level principles (with the GFANZ Guidance); these initiatives also do not go as far as to discuss issues like just transition principles, regional differences between pathways or (more generally) geographic pathways.

Box 10. Guidance on sectoral decarbonisation pathways

Sectoral decarbonisation pathways generally rely on research on carbon budgets and sectoral allocations, using a range of scenarios. Examples include:

- The Global Energy and Climate Model[61] from the International Energy Agency (IEA), which is the agency’s key model for the development of sector- (and region-)specific pathways, with multiple scenarios (e.g., Net Zero by 2050) for different sectors.

- A report from the Institute for Sustainable Futures University of Technology Sydney (UTS) on sectoral pathways.[62] It defines the Global One Earth Climate Model (OECM) 1.5°C Pathway and sectoral pathways for seven sectors.

This research informs initiatives focusing on the development of sectoral decarbonisation pathways for financial institutions:

- The Transition Pathway Initiative (TPI) has defined sectoral decarbonisation pathways,[63] with the latest material released in February 2022. The work sets out emissions benchmarks in 10 high-emitting sectors, against three scenarios. TPI’s pathways are derived from the modelling produced by the IEA.

- GFANZ released guidance to support financial institutions’ use of sectoral pathways[64] in June 2022. It provides a high-level overview of what a pathway should look like (including design principles, such as that they should be comparable, granular, credible etc.). GFANZ focuses on five cross-sectoral pathways to illustrate how the framework can be applied: those from the IEA, UTS and modellers supporting the development of climate scenarios for the Network for Greening the Financial System.

4. What action can be taken?

Our analysis compares investor data needs against the climate data available from a representative sample of data providers. From this analysis, the research has identified three areas of the data ecosystem that might be strengthened to better support investors with the delivery of their net zero commitments (see Figure 7). We recommend that data providers, companies and policy makers and regulators work to:

- Improve corporate disclosure – as corporate data underpins the majority of data products that are currently available, improving corporate disclosure is a pre-requisite to improve the coverage and quality of data products.

- Improve coverage and quality of products – there is a need for data providers to improve coverage, data provider transparency, forward-looking analysis of climate data, and portfolio-level metrics and methodologies.

- Facilitate data comparability – wider consensus-building activities are needed to establish common definitions and agreement on sector and geographic pathways. These would, over time, feed back into the development of data products.

Figure 7. Summary of recommendations

The table below outlines the full set of recommendations identified in the research, grouped by theme. While the recommendations are designed to stand alone, there are clearly overlaps and dependencies, and progress on some would be easier if others were implemented first (e.g., some of the recommendations on data quality first require companies to improve their reporting).