By Toby Belsom, Director of Investment Practices, the PRI and Felix Soellner, Investment Practices Analyst, the PRI

They don’t come much larger than the forthcoming Uber initial public offering. With a proposed multi-billion dollar raise, big name trade relationships such as Toyota, Softbank’s Vision Fund, Paypal – and a long list of investment banks – will be looking to sell equity to global investors.

Over the next week and beyond, global institutional investors will be deciding on Uber’s relative merits or preparing to alter passive funds to adjust for this new shiny arrival. Investment banks will be hoping Uber marks the start of a wave of ‘unicorn’ IPOs – new technology businesses with disruptive businesses models and big valuations. These valuations are often based around forecasts of rapid growth rates, asset light business models, valuable global brands and a new style of management. Uber is one of those businesses that change the way we do things.

Market-savvy businesses emerging from the relative shadow of the private sector may already recognise the impact that ESG issues could have on how customers and regulators perceive them. See Uber’s stated aspiration “to play a meaningful role in creating a sustainable, low-carbon future and addressing environmental challenges” as a crafted response to mitigate against such pressures.

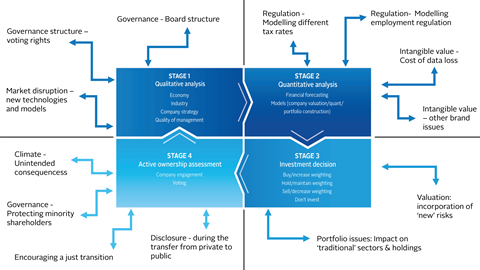

These characteristics make them attractive businesses, but also vulnerable to a range of ESG risks and issues that need to be incorporated into all stages of the investment decision-making process.

Board and ownership structures and protection of minority rights are widely seen as transforming a great private business into a successful investment. Yet many of these newly-floated tech businesses have struggled with this transition. Unlike some of its peers, Uber opted for a single class share structure – something that is to be welcomed. However, new shareholders will remain in the minority with over 2/3 of shares to be held by company executives, former employees and trade partners. For good or bad, these groups will have different incentives and interests to institutional shareholders.

Also, due to their global footprint, asset-light structure and reliance on contractors, these unicorns often have different tax rates to established businesses in mature sectors. Financial regulators have struggled with how to approach businesses such as Amazon Inc with these new business models and tax structures. Yet changes in tax rates can have important implications for profit margins. Perhaps more importantly, unforeseen changes can impact earnings multiples and investor perceptions. How newly-floated businesses respond to criticism around low tax rates will be important on future tax rates and possible risks around regulator changes.

Uber provides a great example of the issues that new technology businesses present for ESG investors. Uber’s model reduces the need for personal car ownership, especially in urban areas, although the model does not necessarily reduce ‘miles travelled’. According to a US study, ride-hailing companies add 2.6 vehicle miles on the road for each mile of personal driving removed.

By way of contrast and in response to the climate challenge, Lyft committed itself to offsetting 100 percent of its caused emissions – making it one of the top 10 global purchasers of carbon credits. The theoretical cost for a similar programme at Uber is $420m pa in the US – a cost that may well become a reality as the energy transition develops.

The application of autonomous vehicles to ride hailing technology and new labour models also poses important just transition questions. The concept of a just transition towards a low-carbon economy is ‘traditionally’ considered an issue in industries such as coal mining because of the energy transition. However, the fact that new disruptive business models (Uber) and technologies (autonomous vehicles and artificial technology) have a large number of current employees has probably greater social implications. A just transition has become a key issue for investors in high carbon emitting industries but these unicorns and Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google stocks might soon become the more significant area of focus.

The concept of a just transition towards a low-carbon economy is ‘traditionally’ considered an issue in industries such as coal mining because of the energy transition. However, the fact that new disruptive business models and technologies have a large number of current employees has probably greater social implications

As with many similar ‘gig economy’ businesses, Uber’s relies on a different employment model. These are often welcomed by employees as providing flexibility, but regulators and traditional competitors have increasingly challenged these new models. Uber’s prospectus recognises the potential implications of these challenges: “If, as a result of legislation or judicial decisions, we are required to classify Drivers as employees …, we would incur significant additional expenses for compensating Drivers, potentially including expenses associated with the application of wage and hour laws.….employee benefits, social security contributions, taxes, and penalties.” These are contributions that most businesses accept as ‘business as usual’.

Though the ownership, storage, transfer and use of data is not unique to these new technology businesses, the scale and sophistication of data storage and use is different. Uber and Lyft have billions of data points about personal journeys and transactions. In the US and the EU, bodies that oversee data security have real teeth. Facebook’s recent Federal Trade Commission privacy probe that resulted in a $3bn fine shows the implications of data issues. Though these fines may be large, probably the greater impact is on the relationship with, and perception by, customers – the basis for the social networks that are critical for the growth of these new disruptive business models.

‘Unicorns’ may not own smokestack factories, have stranded assets or large supply chains in emerging markets. However, these disruptive business models require new ways of analysing and engaging on ESG issues. Engaging with these new management teams and considering these issues in the investment process will make them better investments on the road ahead.

This blog is written by PRI staff members and guest contributors. Our goal is to contribute to the broader debate around topical issues and to help showcase some of our research and other work that we undertake in support of our signatories.

Please note that although you can expect to find some posts here that broadly accord with the PRI’s official views, the blog authors write in their individual capacity and there is no “house view”. Nor do the views and opinions expressed on this blog constitute financial or other professional advice.

If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected].