By Julia Bingler, Council on Economic Policies; Mathias Kraus, University of Erlangen-Nuremberg; Markus Leippold, University of Zurich and Swiss Finance Institute; and Nicolas Webersinke, University of Erlangen-Nuremberg

As the world becomes increasingly aware of the urgent need to act on climate change, more and more companies are making pledges and commitments to help mitigate the problem. Their commitments provide essential information for market participants and regulators and they can influence how the public perceives them. However, with the Earth recording its highest daily average concentration of atmospheric CO2 in the second week of May 2022, it is critical to monitor these pledges and whether their actions speak just as loudly as their words.

How are corporate climate disclosures and commitments evolving?

In our recent study, we analysed 14,584 annual reports, spanning a period of ten years, from the 1,543 companies included in the MSCI World Index (as of January 2021) to assess how effective climate initiatives are at influencing how companies disclose and adhere to their corporate climate commitments.

We developed a methodology based on natural language processing to help investors separate the wheat from the chaff. In particular, we analysed what these companies disclosed as their climate commitments and actions in their annual reports.

We then used ClimateBERT, a large pretrained deep-neural language model, to differentiate between specific (numerical and quantifiable) and non-specific commitments. We used the ratio of non-specific commitments to all commitments as a score to construct a cheap talk index, which served to gauge the quality of companies’ climate commitment disclosures.

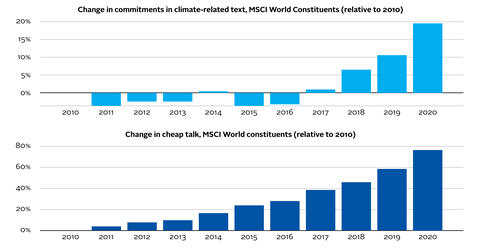

Although our research shows that corporate commitments in climate-related texts increased by nearly 20% between 2010 and 2020 (see Figure 1), we find a rather alarming result: during the same period, the amount of non-specific, descriptive climate commitments – cheap talk – compared with those mentioning specific quantifiable targets, increased by almost 80%.

Figure 1: How climate-related commitments and their cheap talk nature increased among MSCI World Index constituents.

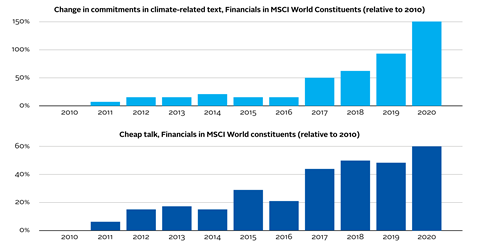

We then focused our analysis on the financial institutions included in the MSCI World Index (see Figure 2). Their commitments increased by more than 150% between 2010 and 2020, many times higher than the MSCI World Index as a whole (almost 20%). At the same time, the amount of cheap talk also increased by more than 60%.

The financial industry therefore appears particularly keen on making climate-related commitments. The coming years will show whether the industry will be able to meet these promises or whether we will see an increase in climate litigations.

Figure 2: How climate-related commitments and their cheap talk nature increased among financial MSCI World Index constituents.

Can climate initiatives affect corporate cheap talk?

With this surprisingly strong increase in cheap talk over recent years, we then considered whether different climate initiatives could help discipline companies to provide decision-useful information. We focused on the members of three climate initiatives: the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD); Climate Action 100+; and the Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi).

We focused on these three initiatives because they serve three different economic channels: signalling (TCFD), engagement (Climate Action 100+), and credibility (SBTi).

Surprisingly, we found that supporting TCFD disclosure recommendations led to an increase in cheap talk, confirming our findings from an earlier paper, while being a Climate Action 100+ target company led to a decrease.

Our SBTi analysis did not provide statistically significant results. However, target setting through SBTi does appear to decrease cheap talk with a delay of one year, albeit only slightly.

Our analysis therefore reveals that out of the three economic channels, it is engagement (e.g. through Climate Action 100+ participation) that compels companies the most to provide specific information on their climate actions.

Why did we use companies’ annual reports for our data?

There are several reasons why we focused on annual reports as a text source and not, for example, earnings calls or sustainability reports:

- Many initiatives, such as the TCFD, encourage their supporters and signatories to publish climate-related information through this channel.

- Annual reports are where stakeholders expect to find financially relevant corporate disclosures and where companies will be legally required to publish climate-related information in the near future.

- The legally binding nature of annual reports provides stronger incentives than corporate sustainability reports to disclose accurately.

- There is ample evidence that disclosures in annual reports are indeed valuable and informative.

Why should we care about cheap talk in annual reports?

In this unprecedented period of economic change, it is challenging for investors to assess the impact of climate change, climate policy, and corporate climate-ambition statements on company value and portfolio strategy.

Financial stakeholders need to understand a company’s climate risk and whether its communicated climate actions and commitments will help to mitigate future transition and physical risks, as well as using this information to actively manage climate-related financial risks and opportunities.

However, we confirm widespread concern among regulators, market participants, and academic researchers for current market inefficiencies: climate risk disclosures are, to date, not sufficiently standardised and lack precision.

Companies are not providing adequately detailed and decision-useful information in their climate-related reporting. Without a concrete plan and follow-through, these voluntary initiatives are nothing more than cheap talk.

Our findings have important implications for investors and financial supervisors.

First, targeted engagement with institutional investors could significantly improve the quality of companies’ climate-related disclosures, particularly when communicating how useful and accurate their climate commitments and actions are for investment decision making.

Policy makers should therefore promote this pathway, for example, by protecting and strengthening investor rights and encouraging investors to engage with their investment partners on climate issues.

Second, companies’ TCFD support is not yet a reliable indicator of corporate climate commitment.

Instead, our results suggest that without additional regulatory provisions, standardisation, and guidance, voluntary or mandatory TCFD-recommended disclosures do not provide information that is accurate enough for stakeholders to make informed investment decisions.

This paper was presented at the PRI Academic Network Week 2022.

The PRI’s academic blog aims to bring investors insights from the latest academic research on responsible investment. It is written by academic guest contributors. Blog authors write in their individual capacity – posts do not necessarily represent a PRI view.