Overview

-

This starter guide introduces the topic of biodiversity to asset owners, focusing on drivers of biodiversity loss while recognising the relevance to the broader concept of nature.

-

It explains the importance and relevance of biodiversity in the context of the investment process and outlines how asset owners might incorporate the issue into responsible investment policies, investment processes and stewardship practices.

-

The guide is split into two parts:

Part 1:

The relevance of biodiversity, covering:

Part 2:

Approaches that asset owners could adopt in their investment process, stewardship and disclosures, including:

Selected further reading is provided throughout the document. For more information on topics raised in this guide, or on biodiversity and nature more broadly, please get in touch.

Part 1: The relevance of biodiversity

What is biodiversity and why is it important?

Biodiversity is the “variability among living organisms from all sources”,1 while nature refers to the “natural world, with an emphasis on its living components”.2 Biodiversity enables ecosystems to be productive, resilient and adaptable to change, which in turn enables ecosystem services such as the provision of food and raw materials, air and water filtration, pollination, carbon storage and climate regulation.

Nature or biodiversity?

This guide focuses on biodiversity and the actions asset owners can take to address the five drivers of biodiversity loss.3 However, the guidance provided acknowledges how natural systems contribute to the maintenance of biodiversity and can therefore be applied to the broader concept of nature for investors seeking to adopt a more holistic approach to nature-related risks and opportunities.

An estimated US$58trn of economic value generation – more than half of the world’s total GDP – is moderately or highly dependent on nature and the ecosystem services it provides.4 Economic activities have an impact on biodiversity by changing its state positively or negatively, which can in turn result in changes to the capacity of the natural world to support ecosystem services. Further estimates suggest that US$7trn is invested annually in economic activities with a direct negative impact on nature.5

Planetary boundaries and climate change

Climate change and biodiversity loss are intrinsically linked; they are crucial to understanding the interplay between planetary boundaries and to minimising the risk of irreversible environmental damage, with six of the nine planetary boundaries crossed as of 2023.6 With climate change categorised as one of the five drivers of biodiversity loss,7 investors can begin identifying synergies within their climate strategies relating to biodiversity risks or opportunities. For example, pursuing circularity within net zero transition technologies can minimise the nature-related impacts of materials extraction and disposal,8 while innovations in regenerative agriculture can mitigate emissions associated with land conversion and promote soil health and resilience.9

Biodiversity is in decline

An unprecedented decline in biodiversity is underway. According to WWF, global wildlife populations have shrunk by 69% on average since 1970.10 The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) finds that 75% of terrestrial and 66% of marine realms have been significantly altered and that more than one million species are currently threatened with extinction.11 The UN Food and Agriculture Organization calculates that 10 million hectares of forest were lost annually between 2015 and 2020.12

Figure 1: Biodiversity Intactness Index, 2020

The index tracks how much of an area’s natural biodiversity remains. The darkest cells indicate high intactness while the lighter cells indicate low intactness.

Source: Natural History Museum

The extent of biodiversity intactness is not equal around the world. There are several biodiversity hotspots that contain a high level of species diversity, many endemic species (species not found anywhere else) and remaining populations of threatened species. Similarly, there are numerous regions where biodiversity intactness is particularly poor, such as in parts of Brazil, the UK and China. The materiality of risks and opportunities will vary depending on geographic location; biodiversity intactness in a given location will be integral to the assessment of nature-related issues.

To understand what is driving biodiversity loss globally, IPBES has identified five human-influenced direct drivers. These are:

-

Land, freshwater and sea-use change from, for example, agricultural expansion, mineral extraction and infrastructure development;

-

Overexploitation of resources through, for example, overfishing, unsustainable timber harvesting, mineral extraction and hunting of species for animal-based products;

-

Climate change, leading to impacts from changing temperatures and weather patterns, which affect how ecosystems function and causing migration of species;

-

Pollution, with impacts to freshwater and ocean habitats as a result of plastic waste and nitrogen deposits, for example; and

-

Invasive species, which can disrupt the ecological functioning of natural systems, for example by outcompeting native flora and fauna.

Why does it matter to investors?

Biodiversity loss presents significant risks for businesses, investors and the wider economy. The unprecedented scale of biodiversity loss currently occurring is a systemic risk contributing to the potential breakdown of financial and natural systems, a phenomenon that would affect all asset classes and sectors.13 It will result in changes to consumer demands as well as regulatory requirements and societal expectations, impacting investors’ asset valuations, allocation processes and portfolio returns.

Biodiversity loss creates new financial risks for investors through two avenues:

-

Impacts: changes in the state of nature (quality or quantity). Examples include a factory polluting a river, or conversion of a natural habitat for infrastructure; and

-

Dependencies: aspects of environmental assets and ecosystem services that a person or an organisation relies upon. For example, a farm might be dependent on ecosystem services such as water flow, pollination or the regulation of hazards like floods.14

Those impacts and dependencies on biodiversity can be unaccounted for or not visible to companies and investors. However, they can materialise into risks that investors must address to protect clients and beneficiaries. These risks can be characterised as:

-

Physical risks resulting from the degradation of biodiversity. They can be chronic or acute and are often location-specific. For example, the loss of protective coastal habitats such as mangroves can increase flood risk, or the loss of wild pollinator insects can reduce yields or increase costs for agricultural businesses. Worst-case estimates from the World Bank suggest that a collapse of just four ecosystem services could result in a US$2.7trn contraction of the world’s GDP by 2030.15

-

Transition risks from the misalignment of economic activities, prompted by changes in regulation and policy, legal precedent, technology, or investor sentiment and consumer preferences. An example would be a failure to meet the due diligence expectations of the 2023 EU Regulation on Deforestation-free products and associated litigation risks.

However, addressing biodiversity loss through conservation and restoration also provides new opportunities for investors. The World Economic Forum has estimated the transition towards economies with a positive impact on nature could generate up to US$10trn in annual value and create 395 million jobs by 2030.16

Examples of nature-related risks and opportunities

Impacts and dependencies on biodiversity, and nature more broadly, materialise as nature-related risks and opportunities in the real world.

Risks

BloombergNEF has compiled a list of 10 leading companies across industries and geographies that have suffered financial losses due to the realisation of nature-related physical and transition risks.17 For example:

- 3M Co., a publicly listed US chemicals multinational, was forced to agree an initial US$10.5bn settlement with US municipal water authorities in June 2023, following claims of water pollution stemming from the release of toxic chemical waste into waterways.

- PG&E Corp, a US-based energy company, went bankrupt after it was found liable for a series of forest fires in California between 2015 and 2018, as a result of poorly maintained infrastructure. The company also agreed to pay US$13.5bn in compensation to victims of the wildfires.

Opportunities

- Mangroves provide more than US$80bn per year in avoided losses from coastal flooding and contribute US$40–50bn per year in non-market benefits associated with various industries.18 Zephyr Power Limited restored mangroves alongside the development of a wind power project in Pakistan, which is projected to save the project developer and its investors up to US$7m over the project’s 25-year lifetime, whilst benefiting the local community.19

- Regenerative agriculture is estimated to provide up to US$1.1 trillion in annual business opportunities by 2030.20 Native, a sugar-producer owned by the Balbo Group, a major sugar-producer in Brazil, has increased its land productivity by 20% through restoring natural processes and adopting various innovations, such as using alternatives to chemical fertilisers and pesticides and specially-adapted harvesting techniques.21

Policy developments

Investors, beneficiaries, regulators and other stakeholders increasingly understand the materiality of biodiversity loss and its indivisibility from broader incorporation of environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors and fiduciary duty. Regulations such as the European Union’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) and Article 29 of France’s Energy-Climate Law have begun to impose mandatory requirements on investors to consider biodiversity in their investments. Other jurisdictions are expected to follow, in light of the adoption of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) by 188 countries at the UN Biodiversity Conference (COP 15) in 2022.

The GBF sets out a framework for action by governments and non-state actors, including business and financial institutions. The mission of this framework is to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030, and includes individual targets such as:

-

The alignment of all global public and private financial flows with this mission (Target 14)

-

The assessment and disclosure of risks, dependencies and impacts on biodiversity by large and transnational companies and financial institutions (Target 15); and

-

The re-alignment of incentives, such as subsidies, with the conservation and restoration of biodiversity (Target 18).

PRI resources:

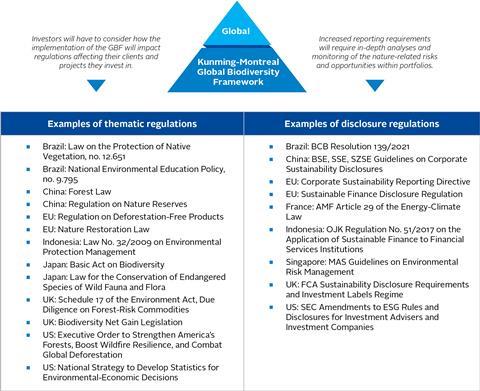

This international effort is mirrored in policy developments at the regional level, such as the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, and within individual jurisdictions (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2: Examples of biodiversity-related regulations around the world

While government action matters, it should not be the only driver for investor action. Given the scale of biodiversity loss and the associated financial risks and impacts, asset owners have a strong incentive to consider the investment implications now rather than later.

“This is a framework for all – for the whole government and the whole of society. Its success [in halting and reversing biodiversity loss by 2030] requires political will and […] action and cooperation by all levels of government and by all actors of society.”

Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework

Part 2: How should asset owners respond?

How asset owners respond to this important challenge will vary. But, as a starting point, they should identify and articulate their position on biodiversity, considering this in relation to their fiduciary duties, the material risks and opportunities they need to manage, and their core values.

This section outlines approaches that asset owners could take to understand risks and take advantage of opportunities related to biodiversity. Readers can also refer to our introductory guide for asset owners on climate change, which follows a similar logic and may help investors identify interlinkages between climate change and biodiversity loss to streamline their internal processes.

A. The investment process

Principle 1: “We will incorporate ESG issues into investment analysis and decision-making processes.”

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to the incorporation of ESG factors, including biodiversity, into an asset owner’s investment process. Practice will vary depending on resources and whether assets are managed internally or externally. However, a comprehensive approach to biodiversity might include the following elements:

-

A public commitment on biodiversity, such as a policy

-

A biodiversity investment strategy

-

The incorporation of biodiversity considerations throughout the investment process.

1. Policy

Asset owners can adopt public commitments on biodiversity, such as a policy. It is good practice for these commitments to be:

-

Approved at the most senior level;

-

Communicated throughout the organisation; and

-

Integrated into governance frameworks, management systems, investment beliefs, policies and strategies to inform investment decisions, stewardship of investees and policy dialogue.

Developing a biodiversity policy: A technical guide for asset owners and investment managers guides investors through the process for developing a biodiversity policy. It sets out a five-step process for developing an organisational approach to biodiversity, designed to guide organisations through a deliberate progression of understanding biodiversity considerations, integrating them into investment processes, and managing and disclosing the associated risks and opportunities.

Example: Groupe Caisse des Dépôts’ biodiversity policy

French financial institution Groupe Caisse des Dépôts has developed a biodiversity policy covering all the group’s entities. The policy is structured around IPBES’s five impact drivers of biodiversity and ecosystem change, and includes a commitment to meet national and international biodiversity goals in line with the GBF; currently, Groupe Caisse des Dépôts is working on tailoring the targets outlined in its policy so they are more closely aligned with the framework. For example, it recently set a target to invest €5bn towards nature to align with Target 19 of the GBF.

The policy is divided into four areas: footprint measurement; the reduction of direct and indirect negative impacts; increase of direct and indirect positive impacts; and contribution to research, training and awareness raising. Each area includes additional information, including commitments or expectations, which will be monitored through a set of key performance indicators.

PRI resources:

2. Investment strategy

Asset owners can also develop a biodiversity strategy to respond to biodiversity loss. The strategy should prioritise the most material risks and opportunities as identified by an assessment, or similar exercise. Within a biodiversity strategy, asset owners may also detail objectives, commitments or specific targets, including whether they align with international or industry biodiversity frameworks.

Steps within a biodiversity strategy might include:

-

Identifying the investment strategy purpose and baseline – for example, measuring exposure to biodiversity impacts, dependencies, risks and opportunities to set the strategy’s key objectives;

-

Defining the appropriate internal governance and accountability, as well as internal training and awareness-raising, to support the achievement of investment strategy targets;

-

Assessing biodiversity-related opportunities across asset classes, such as nature-based solutions, biodiversity-focused funds and green infrastructure; and

-

Establishing mechanisms for reviewing the strategy regularly and reporting on its effectiveness.

Example – Desjardins Global Asset Management: Enhancing investments with ESG integration and biodiversity metrics

Desjardins Global Asset Management (DGAM) has built a responsible investment strategy which focuses on four priority ESG themes, including protection of biodiversity and natural capital. In 2022, it signed the Finance for Biodiversity Pledge, committing to protect and restore biodiversity through its finance activities and investments. For DGAM’s private market investments (infrastructure and real estate portfolios), biodiversity metrics covering waste, water, land use and wildlife fatalities are incorporated into due diligence and asset assessment processes. For public markets, DGAM integrates biodiversity into its ESG evaluation, when it is material to the sector, through its integration into the quantitative analysis using database metrics, and through the qualitative review of sector companies focusing on their impacts and risks to nature. In 2023, its engagements prioritised 11 companies specifically for biodiversity dialogues, spanning multiple material issues including deforestation, water use and quality, waste management, plastic pollution and the development of a nature roadmap.

Related resources:

-

Embedding ESG issues into strategic asset allocation frameworks

-

Asset owner strategy guide: How to craft an investment strategy

-

Understanding and aligning with beneficiaries’ sustainability preferences

-

TNFD Guidance on the identification and assessment of nature-related issues: the LEAP approach

-

Finance for Biodiversity Nature Target Setting Framework for Asset Managers and Asset Owners

3. Incorporating biodiversity considerations throughout the investment process

How asset owners implement their biodiversity-related policy commitments and strategies in their investment processes will vary depending on whether they manage funds internally or through external managers. Whether investing internally or externally, however, a critical step for all asset owners is to begin to assess portfolio exposure to biodiversity-related risks, opportunities, impacts and dependencies, for example using the LEAP assessment framework from the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD), Finance for Biodiversity’s Nature Target Setting Framework for Asset Managers and Asset Owners, or Global Canopy’s Finance Sector Roadmap for Eliminating Commodity-Driven Deforestation.

Example: AP2’s deforestation risk tool

Swedish pension fund AP2, in collaboration with the sustainable finance think-tank Climate & Company, is developing a publicly accessible methodology and practical guidance to assess each investee company within its portfolio for deforestation risk. The guidance will build on several existing databases, such as those from Forest500 and Trase, but it will be relevant for all portfolio companies and will consider both location and activities for assessing risk. The guidance will help AP2 integrate deforestation information in the investment process and identify those investee companies with deforestation risk, helping to prioritise engagement. This systematic guidance will help AP2 achieve its commitment to have a portfolio that does not contribute to deforestation by 2025.

Direct investors

Asset owners that manage funds internally can integrate the findings of a biodiversity risk assessment into, for example, pre-investment analysis and due diligence of portfolio companies and assets, or develop screening methodologies using biodiversity-related criteria. The findings can also help identify potential targets for engagement (see below).

PRI resources:

Selection, appointment and monitoring of investment managers

Similarly, asset owners should assess how external managers’ approaches to biodiversity align with their own during due diligence and as part of ongoing monitoring.

Below are examples of questions that asset owners can ask their managers during these processes, noting that this is not a comprehensive list but a basis for discussion and for gathering further information.

-

Governance

- Has your organisation included the monitoring of biodiversity-related issues as part of the board’s and/or management group’s oversight responsibilities?

- How is progress on biodiversity action reviewed, by whom and how often?

- Does your organisation have sufficient experience and knowledge of biodiversity/nature, both individually and as a team? If not, does the company provide any training?

- Do you have a firm-wide or business area-specific investment policy on biodiversity?

-

Strategy

- Is there an organisation-wide or business area-specific strategy in place to identify risks, opportunities, impacts and dependencies related to biodiversity?

- How is biodiversity integrated into strategic and tactical asset allocation?

-

Risk management

- Has a process been established to assess, measure and integrate biodiversity-related investment risks (physical, transition and systemic) into risk monitoring and stewardship activities?

- What biodiversity-related risks and opportunities, dependencies and impacts have been identified for your investments/assets?

- What is your process for incorporating these risks in your investment decision-making process?

-

Targets and metrics

- What biodiversity-related metrics, if any, does your organisation use, and why have these metrics been selected?

- Can you describe how these metrics have affected investment decisions or informed stewardship activities?

- Has the organisation set itself biodiversity-related targets?

-

Disclosure

- Does your organisation disclose and report on its risks, opportunities, impacts and dependencies on biodiversity?

- How often does your organisation disclose and report on its risks, opportunities, impacts and dependencies on biodiversity?

- Does your organisation require or expect its portfolio companies to disclose and report on their risks, opportunities, impacts and dependencies on biodiversity?

- If not, please explain the rationale behind this decision.

- If so, do you (and your portfolio companies) align with any specific framework or guidance, such as the TNFD Disclosure Recommendations?

Asset owners’ engagement with managers should also take into account that managers’ abilities to assess biodiversity-related risks and opportunities may be limited given, for example, weaknesses in existing datasets, the lack of established biodiversity metrics, or the lack of a common understanding of how to translate biodiversity information into financial materiality.

PRI resources:

Example: Forestry fund selection at Stafford Capital Partners

Stafford Capital Partners has several criteria it considers when selecting a forestry fund to invest in. As an initial screening of funds, it does not invest in natural forests, due to high risk and weak governance in the jurisdictions where natural forests tend to be situated. This limits Stafford Capital Partners to countries that have relatively strong tenure frameworks and sustainable forestry management practice. The firm also ensures that funds meet SFDR Article 9 requirements.

Once funds are selected, Stafford Capital Partners undertakes environmental impact assessments before planting trees and other vegetation to identify priority restoration sites to focus efforts on. Once invested, Stafford Capital Partners will engage with the fund manager to tailor the right approach and reporting metrics, and conducts regular audits of the assets to ensure they are being managed sustainably.

B. Stewardship

Principle 2: “We will be active owners and incorporate ESG issues into our ownership policies and practices.”

Principle 4: “We will promote acceptance and implementation of the Principles within the investment industry.”

Principle 5: “We will work together to enhance our effectiveness in implementing the Principles.”

Stewardship is the use of influence by investors to protect and enhance overall long-term value, including the value of common economic, social and environmental assets, on which returns and client and beneficiary interests depend. Irrespective of asset class, and whether investments are made directly or through external fund managers, all asset owners can be active owners of their investments and engage on biodiversity.

Possible actions include:

-

Developing and disclosing an active ownership policy that includes biodiversity-related issues;

-

Exercising voting rights or monitoring compliance with voting policy (if outsourced) with respect to biodiversity-related issues;

-

Filing biodiversity-related shareholder resolutions consistent with long-term ESG considerations;

-

Participating in the development of policy, regulation and standard-setting that supports governments in meeting the aims and objectives of the GBF; and

-

Participating in collaborative engagement initiatives such as Spring, the Investor Policy Dialogue on Deforestation Initiative, FAIRR’s waste and pollution engagement, the Valuing Water Finance Initiative, Finance Sector Deforestation Action and Nature Action 100.

Example: Green Century Capital Management’s engagement with portfolio companies

Green Century Capital Management considers engagement with investee companies a priority activity in its biodiversity (and overall ESG) agenda. If a portfolio company is found to be lagging on a material biodiversity issue, such as deforestation, soil degradation or plastic waste, Green Century will first engage in dialogue with the company to try to address the issue. If further action is necessary, it will file a resolution, either collaboratively with other shareholders or individually, urging the company to set out a concrete commitment to improve. Once such a commitment is made, the firm will routinely check in with the company to offer support and monitor progress against the commitment. In 2023, Green Century deployed this approach to convince Kraft Heinz to adopt a comprehensive global forest protection policy.

PRI resources:

C. Disclosure

Principle 3: “We will seek appropriate disclosure on ESG issues by the entities in which we invest.” Principle 6: “We will each report on our activities and progress towards implementing the Principles.”

Asset owners should disclose their own biodiversity-related policies, practices and impacts, as well as requiring disclosure from investee companies, issuers and external investment managers.

Through regular reporting, asset owners can keep beneficiaries and other stakeholders informed of their progress addressing biodiversity loss. This reporting can take many forms, including sustainability reports and the publication of case studies. The PRI’s Reporting Framework provides signatories with the opportunity to disclose information about their approach to biodiversity.

Possible actions include:

-

Disclosing how biodiversity-related issues are incorporated into investment practices;

-

Disclosing stewardship activities related to biodiversity, such as engagement and voting;

-

Engaging with investee entities to measure and disclose their biodiversity risks, opportunities, impacts and dependencies;

-

Aligning disclosure asks and own practices with TNFD disclosure recommendations;

-

Communicating with beneficiaries about biodiversity-related issues; and

-

Reporting on progress and/or achievements relating to biodiversity.

Disclosure practices related to biodiversity, and nature more broadly, have significantly changed over recent years, in particular with the work of the TNFD.

The TNFD provides disclosure recommendations for investors and companies to assess and disclose nature-related risks and opportunities, in particular where regulation does not yet exist. It recommends that organisations disclose against questions related to governance, strategy, risk and impact management, and targets and metrics. The TNFD has identified a set of core global metrics, complemented by core sector-specific metrics, all to be disclosed by businesses on a comply or explain basis.

The TNFD disclosure recommendations are now being considered for integration and alignment within international standards. They were included in the revised GRI Biodiversity Standard, released in 2024.

Related resources:

Downloads

An introduction to responsible investment: Biodiversity for asset owners

PDF, Size 1.06 mbIntroduction à l’investissement responsable la biodiversité pour les investisseurs institutionnels (French)

PDF, Size 0.99 mbIntrodução ao investimento responsável: Biodiversidade para proprietarios de ativos (Portuguese)

PDF, Size 3.14 mb責任投資の入門ガイド:アセット・オーナー向け生物多様性ガイド (Chinese)

PDF, Size 1.19 mbIntroducción a la Inversión responsable: Biodiversidad para propietarios de activos (Spanish)

PDF, Size 3.99 mb

References

1 Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (2011), Convention on Biological Diversity: Texts and Annexes

2 IPBES (2019), Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services

3 IPBES, Models of drivers of biodiversity and ecosystem change

4 PwC, “PwC boosts global nature and biodiversity capabilities with new Centre for Nature Positive Business, as new research finds 55% of the world’s GDP - equivalent to $58 trillion - is exposed to material nature risk without immediate action”, press release, 19 April 2023

5 UNEP (2023), State of Finance for Nature 2023

6 Richardson, J., Steffen W., Lucht, W., Bendtsen, J., Cornell, S.E., et.al. (2023), “Earth beyond six of nine Planetary Boundaries”, Science Advances, 9, 37

7 IPBES, Models of drivers of biodiversity and ecosystem change

8 The Ellen MacArthur Foundation, What is a circular economy?

9 The World Economic Forum, “5 benefits of regenerative agriculture – and 5 ways to scale it”, article, 11 January 2023

10 WWF (2022), Living Planet Report 2022

11 IPBES (2019), Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services

12 FAO (2022), The State of the World’s Forests 2022

13 The Network for Greening the Financial System, “NGFS acknowledges that nature-related risks could have significant macroeconomic and financial implications”, press release, 24 March 2022

14 TNFD (2023), Glossary Version 1.0

15 The World Bank (2021), The Economic Case for Nature

16 The World Economic Forum (2020), The Future Of Nature And Business

17 BloombergNEF (2023), When the Bee Stings - Counting the Cost of Nature-Related Risks

18 Global Commission on Adaptation and WRI (2019), Adapt Now: A Global Call for Leadership on Climate Resilience

19 Earth Security (2020), Financing the Earth’s Assets: The Case for Mangroves

20 The World Economic Forum (2020), The Future Of Nature And Business

21 The Ellen MacArthur Foundation, Regenerating an ecosystem to grow organic sugar: The Balbo Group, case study, 24 February 2021