Expectations have been driven not only by growing visibility and urgency around many human rights issues, but also by a better understanding of investors’ role in shaping real-world outcomes, and of their responsibility to do so – across all their investment activities.

With regulation on human rights due diligence already implemented in some jurisdictions, more measures in the pipeline and policy making converging around the UNGPs and OECD standards, investors can future-proof their approach to ESG issues by implementing these frameworks now. Leading investors also recognise that meeting international standards – and preventing and mitigating actual and potential negative outcomes for people – leads to better financial risk management, and helps to align their activities with the evolving demands of beneficiaries, clients and regulators.

How to respect human rights in investment activities

Institutional investors have a three-part responsibility to respect human rights:

- policy commitment;

- due diligence processes;

- enabling or providing access to remedy.

| POLICY | DUE DILIGENCE PROCESSES | ACCESS TO REMEDY | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adopt a policy commitment to respect internationally recognised human rights | Identify actual and potential negative outcomes for people, arising from investees | Prevent and mitigate the actual and potential negative outcomes identified | Track ongoing management of human rights outcomes | Communicate to clients, beneficiaries, affected stakeholders and publicly about outcomes, and the actions take | Enable or provide access to remedy |

To effectively implement the due diligence and access to remedy requirements, investors can use their investment decisions, stewardship of investees and dialogue with policy makers and other stakeholders. To understand their exposure and the actions required, investors need to request information from throughout the value chain: from their investment managers, other service providers and/or investees. Investors set expectations and influence others – to know, act on and show how they manage harm to people arising from their business activities and relationships.

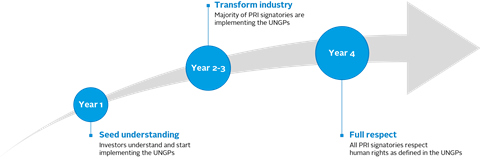

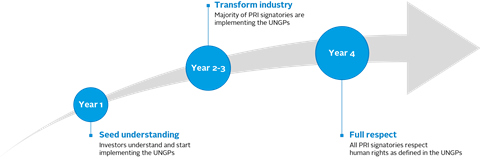

Next steps for the PRI

We are setting out a multi-year agenda for our work towards respect for human rights being implemented in the financial system.

The PRI will:

- support institutional investors with their implementation of the UNGPs through knowledge-sharing, examples and other practical materials;

- increase accountability among signatories, by introducing human rights questions into the PRI Reporting Framework – initially on a voluntary basis;

- facilitate investor collaboration to address industry challenges to implementing respect for human rights;

- promote policy measures that enable investors and investees to manage human rights issues;

- drive meaningful data that allows investors to manage risks to people.

The financial industry must play a critical role in facilitating sustainable development and growth, and in ensuring that people’s fundamental dignity and rights are upheld.

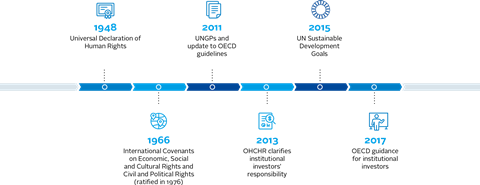

Institutional investors’ responsibility to respect human rights is defined – as for all other businesses – in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs).1 The UNGPs were formally and unanimously endorsed by the UN Human Rights Council in 2011, and immediately reflected in the OECD’s Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises.2 Since then, expectations – from employees, beneficiaries, clients, governments and wider society – have only increased, driven not only by growing visibility and urgency around many human rights issues, but also by a better understanding of investors’ role in shaping real-world outcomes, and of their responsibility to do so – across all their investment activities.

Failure to respond to these expectations can erode trust, jeopardising the financial industry’s social license to operate. Media, governments and citizens are questioning whether the global financial system serves its intended purpose, and the wider interests of society, if it fails to manage capital in a way that supports sustainable and inclusive economies. The climate emergency, decades of widening economic inequality and the COVID-19 pandemic are all drawing focus on investors’ behaviour.

Meeting human rights expectations leads corporates and investors to more effectively and proactively manage a range of complex environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues. Among social issues, we find employee relations, diversity issues, health and safety, community relations and forced labour – each of which are reflected in well-established international human rights instruments. Many issues that are often categorised as environmental or governance issues – such as access to water, tax fairness and climate justice – also have a clear human rights basis.

We have seen momentum in governments championing human rights and embedding their expectations of investors into law and regulation. The extent to which human rights are protected by states varies between jurisdictions, and where they fall short, business entities’ responsibility to operate to higher international standards remains. With further regulation on human rights due diligence in the pipeline4, and policy making converging around the UNGPs and OECD standards, investors can future-proof their approach to ESG issues by implementing these frameworks now.

Respect for human rights is fundamental to advancing the SDGS

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set the global goals for societies and all its stakeholders – including investors – and are explicitly grounded in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights has explicitly mapped the overlap between the SDGs and human rights.

The implementation of the UNGPs across business and investment activities has the potential to deliver a transformational contribution towards achieving the SDGs. By addressing the full range of human rights, corporates and investors could, amongst other things:

- address gender-related issues connected to business activities, helping achieve up to eleven SDGs;

- provide workers with a living wage, advancing eleven of the SDGs;3

- eradicate forced labour from the value chain, contributing to the advancement of six SDGs.

This overlap between the SDGs and human rights does not detract from the inalienable nature of human rights themselves: the potential failure of companies or investors to prevent or mitigate harm to people cannot be offset by targeted initiatives to contribute to one or multiple SDGs.

The PRI has developed a five-part framework for Investing with SDG outcomes.

Leading investors recognise that meeting international standards – and preventing and mitigating actual and potential negative outcomes5 for people – also leads to better financial risk management, and helps to align their activities with the evolving demands of beneficiaries, clients and regulators. However, many institutional investors are either unaware or unclear on how to fulfil their responsibility to respect human rights.

This paper sets out the PRI’s expectation that investors respect human rights across all their investment activities, as defined by the UN and OECD.

For specific technical guidance, we direct investors to resources developed by the OECD and the Investor Alliance for Human Rights. We also outline upcoming initiatives to support signatories and address challenges to promote human rights in the financial industry.

Ensuring respect for human rights is central to achieving our 10-year Blueprint for responsible investment, which aims to bring responsible investors together to work towards sustainable markets that contribute to a more prosperous world for all.

Defining human rights

The idea of human rights is as simple as it is powerful: that people have a universal right to be treated with dignity. Every individual is entitled to enjoy human rights without discrimination – whatever their nationality, place of residence, sex, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, language or any other status. Human rights are interrelated, interdependent and indivisible.

Business enterprises’ responsibility to respect human rights is based on internationally recognised human rights – understood, at a minimum, as those expressed in the following instruments:

| International Bill of Human Rights (comprising the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and its two Optional Protocols) | International Labour Organization’s Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work and the eight core conventions | |

|---|---|---|

| EXAMPLES |

|

|

Additional human rights instruments have elaborated on the human rights of people belonging to particular groups or populations – for example children, ethnic or religious minorities and indigenous people – recognising that they may need specific protection to fully enjoy human rights without discrimination. Some jurisdictions also have regional and national instruments with more stringent requirements.6

The promotion and protection of human rights is articulated in international law. Initially the Universal Declaration of Human Rights sets out: “a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations, to the end that every individual and every organ of society […] shall strive […] to secure their universal and effective recognition and observance”. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and theInternational Covenant on Civil and Political Rights go on to codify this standard in legally binding agreements between states. Together these three documents constitute the International Bill of Human Rights.

The reference to “every organ of society” was, however, typically interpreted as referring only to states, with the responsibilities of businesses – including institutional investors – not clearly defined. This changed with the unanimous endorsement of the UNGPs by the UN Human Rights Council in 2011. The UNGPs clarified that all business enterprises have a responsibility to respect human rights through a set of policy and process requirements. In 2013, the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) specifically clarified that the UNGPs apply to institutional investors.7

UN guiding principles on business and human rights

The UNGPs are the authoritative standard on corporate conduct on human rights. They are widely supported and adopted by states, regional institutions and multilateral organisations – and are a focal point around which policy around the world is converging.

- Member states on the Human Rights Council at the time of endorsement of the UNGPs included Brazil, China, Russia, Saudi Arabia, the UK and the US.

- Chile, Colombia, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Netherlands, Norway, Italy, Spain, Switzerland, Tanzania, Thailand, Kenya, UK and the US – among others – have since incorporated the UNGPs in national action plans.8

- France has incorporated the expectations of the UNGPs in its Duty of Vigilance Law, and the EU and other members states are in the process of introducing similar legislation.

- Other countries and states have implemented due diligence legislation for specific human rights – for example Australia, California and the UK for modern slavery and the Netherlands for child labour.9

- The European Union’s CSR strategy, its regulation on sustainability-related disclosures in the financial services sector and its Taxonomy for sustainable activities’ minimum social safeguards, all reference the UNGPs.

- The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the African Union are also working with the UNGPs in regional frameworks.

- In addition, the UNGPs are integrated into:

- OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises;

- ISO 26000, which reflects core aspects of corporate responsibility to respect human rights in its human rights provisions;

- the IFC Performance Standards, which incorporate the concept of the corporate responsibility to respect human rights in Performance Standard 1.

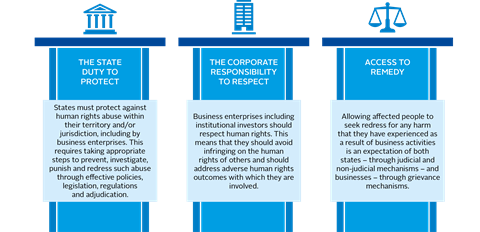

The UNGPs consist of three pillars

OECD guidelines for multinational enterprises

In 2011, the same year that the UNGPs were unanimously endorsed, the OECD updated their Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (Guidelines) to reflect the UNGPs as the global, authoritative standard on human rights.10 The Guidelines reflect the expectation from governments to businesses on how to act responsibly. They bring together all thematic areas of business responsibility, including human and labour rights.

The Guidelines are an international legal instrument that have been formally adhered to by 49 governments, making a formal commitment to promote them amongst companies operating within or from their territories. Businesses including institutional investors can be subject to complaint cases via an OECD National Contact Point (NCP) if they fail to meet the standards. This is a formal grievance process through which stakeholders may lodge allegations of non-observance. NCPs offer mediated dialogue on issues and publish statements describing the outcome of the proceedings.

After a number of NCP cases against institutional investors, in 2017 the OECD – following extensive collaboration with the financial industry – released detailed technical guidance on how institutional investors should comply with the Guidelines, including their responsibility to respect human rights.

Investor initiatives

There is also emerging momentum on human rights among institutional investors themselves:

- In the past five years, approximately 115 institutional investors with more than US$13 trillion of assets under management (AUM) have engaged with 100 companies through PRI-led collaborative engagements to improve human rights practices and disclosure, using the UNGPs as the reference.11

- More than 180 PRI signatories apply to their investment portfolios various forms of screening referencing the UNGPs and/or the OECD Guidelines.12

- A growing number of companies (currently 152) are disclosing information through the UN Guiding Principles Reporting Framework – an initiative backed by 88 investors with US$5.3 trillion in AUM.

- TheCorporate Human Rights Benchmark – an investor- and civil society-led initiative – assesses the human rights performance of more than 200 of the largest publicly traded companies.

- An investor call for governments to legislate on mandatory due diligence for companies led by the Investor Alliance for Human Rights is currently supported by 105 investors with US$5 trillion in AUM.

Since the UNGPs were endorsed in 2011, the PRI has applied them as the overarching framework for projects relating to social issues, including PRI-coordinated collaborative engagements. While there has been significant progress made by some investors and companies in relation to human rights, investors – as part of their own human rights due diligence – can reinforce the need for corporates to better manage human rights risks and disclosure, in line with the UNGPs. This can better inform their own investment decision-making, stewardship activities and policy engagement – and ultimately improve outcomes for people.

Institutional investors’ responsibility to respect human rights encompasses both their own operational activities – for example in relation to employees, clients, communities, and contractors – and the outcomes they are connected to through their investments. This paper focuses on the latter.

How investors are connected to outcomes

Investors’ focus should be on understanding a) which actual and potential negative human rights outcomes they are connected to through their investments, and b) how they are connected to them. This will determine what expectations there are on the investor to prevent and mitigate negative outcomes, and what role they should play in providing or enabling access to remedy.

There are three ways in which an institutional investor can be connected to a human rights outcome. There are outcomes that an investor:

- has caused – through its own business activities13 (e.g. outcomes on its own employees). An investor can “cause” negative human rights outcomes where its own activities remove or reduce someone’s ability to enjoy a human right. This will typically be in relation to their operational activities, but where the investor holds a controlling stake in an investee company (e.g. through the majority ownership model in private equity), it can also occur through their investment activities.14

- has contributed to – a) through its own business activities where it is one of several contributors or b) through a business relationship or investment activity that induces or facilitates an outcome from an investee company or project. This could occur through investments when the investor holds high ownership stakes and could or should have known about harm, but preventive actions were insufficient.

- is directly linked to – through the activities, products or services of an investee company or project.

An investor’s connection to an actual or potential outcome will change over time. Three factors in particular will determine whether an investor can be said to have ”contributed to” or be ”directly linked to” a negative outcome:

- the extent to which an investor facilitated or incentivised human rights harm by another;

- the extent to which it could or should have known about such harm;

- the quality of any mitigating steps it has taken to address it.

Investors’ responsibility to manage actual and potential negative human rights outcomes in their portfolio does not replace the responsibility of the companies themselves, and vice versa. Companies will primarily be the ones causing or contributing to negative outcomes.

A three-part responsibility

Institutional investors should meet their responsibility to respect human rights by: publishing a policy commitment, having due diligence processes and enabling or providing access to remedy.

The policy commitment and due diligence processes should cover, at a minimum, the human rights included in the international legal instruments listed in the Defining human rights section above.

Institutional investors should embed their human rights policy commitment into their investment governance framework and management systems.

They can then use their investment decisions, stewardship of investees and dialogue with policy makers and other stakeholders to effectively implement the due diligence and access to remedy requirements, in line with the UNGPs and OECD Guidelines. These activities are expected even when states fall short in the protection of human rights.

Unlike investors’ traditional risk management systems – which focus on business risk, operational risk or financial risk – the core component is a focus on the risk of negative outcomes for people.

| STEPS | ACTIONS | |

|---|---|---|

| POLICY | Adopt a policy commitment to respect internationally recognised human rights | Embed the policy commitment to respect human rights, approved at the most senior level, throughout the organisation with proper resourcing, and by integrating it in governance frameworks, management systems, investment beliefs, policies and strategy to inform investment decisions, stewardship of investees and policy dialogue. |

| DUE DILIGENCE PROCESSES | Identify actual and potential negative outcomes for people, arising from investee |

Investment decisions The management of actual and potential negative human rights outcomes should be reflected in the investment decision-making process, including in portfolio construction, security selection and asset allocation, and/or in selecting, appointing and monitoring external managers/funds and other services providers.

Stewardship of investees Using the rights and/or position of ownership in an asset – individually or in collaboration with other investors – to influence the activity or behaviour of existing or potential investees is necessary to prevent and mitigate negative human rights outcomes, and to enable access to remedy when an actual negative outcome has occurred and the investor is linked to it. Engagement and voting are key tools for this. Dialogue with policy makers and key stakeholders Preventing potential negative human rights outcomes and mitigating and enabling access to remedy in cases of actual harm can require policy interventions, ranging from regulation on human rights performance and disclosure to specific socio-economic policies. Investors can work with others (e.g. policy makers, regulators, multilateral organisations and stock exchanges) to develop or influence market and industry standards that foster an enabling environment for investment that respects human rights. Responsibilities also include refraining from lobbying against positions or legislation seeking to improve protection of human rights. |

| Prevent and mitigate the actual and potential negative outcomes identified | ||

| Track ongoing management of human rights outcomes | ||

| Communicate to clients, beneficiaries, affected stakeholders and publicly about outcomes, and the actions taken | ||

| ACCESS TO REMEDY | Provide or enable access to remedy | Investors are responsible for providing access to remedy for people affected by their investment decisions when the investor is either contributing to or causing the negative outcomes. For outcomes the investor is directly linked to through an investee, the investor should use and build influence to ensure that investees provide access to remedy for people affected |

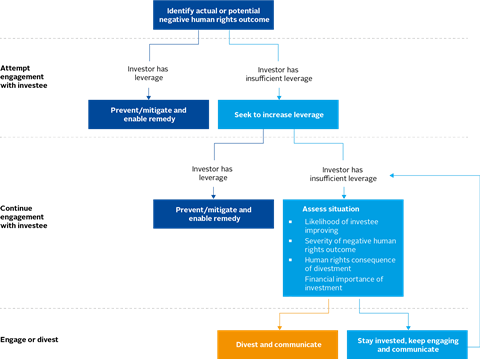

Severity and leverage

The concepts of severity and leverage (meaning influence, rather than debt) are commonly used to guide investors to focus and sequence activities, and to determine which actions to take.

Severity

While human rights cannot in themselves be ranked15, assessing which actual or potential negative outcomes for people are most severe – in the context of specific business activities or investments – can help prioritise which issues to deal with first. This does not limit the overall responsibilities to manage all adverse human rights outcomes over time.

Assessment will include reviewing the scale of the outcome (on an individual right(s)), the scope (number of individuals affected) and the irremediable character (any limits on the ability to restore those affected to a situation at least equivalent to their previous situation).

The severity of human rights issues should be assessed from the perspective of potentially impacted stakeholders – whose inputs are important in that process – rather than in terms of financial materiality. There can, however, be overlaps: while the focus of human rights due diligence processes is the risk to people, it can pick up issues that, left unaddressed, would go on to become financially material. Assessing a company’s human rights due diligences process can therefore also be a good way to assess its overall governance and potential future financial risk.

Leverage

Institutional investors need to be able to influence investees and other stakeholders to change the wrongful practices of another party that is contributing to or causing harm. The UNGPs16 and OECD Guidelines17 refer to this as “leverage”. Investors can exercise, and build, leverage through all of the actions in the table above – through their investment decisions, stewardship of investees and dialogue with policy makers and key stakeholders.

Options to influence an investee while invested vary across investment instruments. For some financial instruments, leverage can (and therefore should) be applied both pre- and post-investment.

- Equity investors will have more direct mechanisms for influence through stewardship activities and proxy voting rights.

- Private equity investors with board positions and negative control rights will have greater direct influence, including the option to replace management.

- Sovereign bondholders often have limited influence and are restricted by sovereign entities being principally accountable to their citizens.

- Investors in illiquid assets (except where strong ownership mechanisms exist such as in private equity) will often have limited leverage even once invested, so should pay closer attention to identifying human rights risks and to articulating expectations pre-investment.

If an investor lacks leverage, it should seek ways to increase it, including through collaboration with other investors. While stewardship is just one way that investors can exercise and build leverage, investors that are used to engaging – individually or collectively – with companies on ESG issues will be familiar with the mechanisms.

If the investor is unable to establish enough leverage to alter the behaviour of the investee sufficiently to prevent or mitigate a negative outcome, and there is no prospect for improvements, they could consider whether they can justify staying invested. The severity of negative human rights outcomes and the human rights consequence of divesting should, however, always be considered first.

As a last consideration, the investor will need to consider how crucial the investment is for their investment strategy or portfolio from a financial perspective. An investor might not be deemed able to fulfil their given mandate – for example pension provision – if they divest or exit, or where they are subject to asset allocation requirements. In such cases – i.e. where the investor cannot establish enough leverage to address a negative human rights outcome and is unable to divest – they should document the steps taken and their reasoning for continuing to stay invested, and communicate this to clients, beneficiaries, affected stakeholders and other relevant parties. They should be ready to justify their approach and decision, and to accept the potential consequences – reputational, financial and legal – of their continued investment.

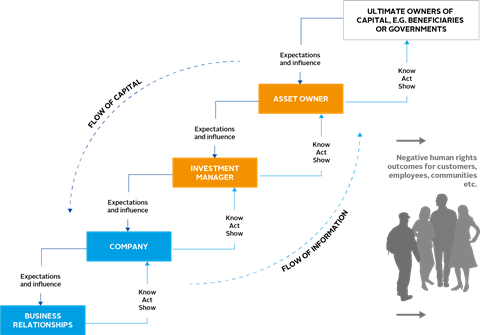

Influencing the value chain

All entities in the value chain can be connected to human rights outcomes, and therefore have a responsibility to respect human rights: to manage actual and potential negative outcomes for people.

To understand their exposure and the actions required, asset owners need to request information from their investment managers, other service providers and/or investees, as relevant.

The flow of information allows, for example, a pension fund with outsourced investment management to be aware of the human rights outcomes that they are linked to through their portfolio. As human rights due diligence is often lacking, investors should actively work to fill information gaps, through service providers, NGOs, governments, media, trade unions and affected rightsholders or their representatives.

Simplified value chain: investors set expectations and influence companies to know, act on and show how they manage harm arising from their business activities and relationships.

In practice the value chain – and the flow of information and capital – is often further complicated through the use of investment consultants, fund-of-funds, benchmark administrators, engagement providers, stock exchanges or other financial intermediaries.

Nevertheless, asset owners are in the position to set expectations and influence the practices of third-party investment managers, service providers and investees (who all have an independent responsibility to respect human rights).

The responsibility set out in this paper builds on recognised international standards, such as the UNGPs and the OECD Guidelines. We provide a high-level overview of expectations, and highlight the following guidance documents for further technical details and examples of how to implement respect for human rights in investment activities:

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)’s Responsible Business Conduct for Institutional Investors helps institutional investors implement the due diligence recommendations of the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, in order to prevent or address adverse outcomes – related to human and labour rights, the environment and corruption – in their portfolios.

- The Investor Alliance for Human Rights (IAHR)’s Investor Toolkit on Human Rights provides investors with a stepby-step framework, along with checklists, templates and case studies from investors for each step.

In the midst of a global climate emergency, escalating inequality and the COVID-19 pandemic, many voices are calling for a more people-focused economic and societal model. This is paramount to address the inadequacies and unsustainable nature of our current financial and economic system. International human rights standards, the SDGs and the Paris Agreement are the universal frameworks that must shape the sustainable economic recovery and the system reforms that the world needs.

We are therefore setting out a multi-year agenda for our work towards respect for human rights being implemented in the financial system.

THE PRI WILL:

- support institutional investors with their implementation of the UNGPs through knowledge-sharing, examples and other practical materials;

- increase accountability among signatories, by introducing human rights questions into the PRI Reporting Framework – initially on a voluntary basis;

- facilitate investor collaboration to address industry challenges to implementing respect for human rights;

- promote policy measures that enable investors and investees to manage human rights issues;

- drive meaningful data that allows investors to manage risks to people.

We will work with signatories and key partners to deliver on this work programme to ensure that our financial and economic system respects both the boundaries of the planet and the rights of its people. The financial industry must play a critical role in facilitating sustainable development and growth, and in ensuring that people’s fundamental dignity and rights are upheld.

The answers below aim to address some common misconceptions surrounding investors’ responsibility to respect human rights. Investors can also find a number of resources that can help them engage more deeply with human rights in their investment activities.

Aren’t human rights only relevant for states?

The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (OECD Guidelines) articulate that businesses have a responsibility to respect human rights that exists independently of a state’s duty to protect human rights. Where a state falls short of its human rights obligations, businesses must still, to the greatest extent possible, adhere to higher international standards.

Since the publication of these guidelines, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and the OECD have explicitly stated that both frameworks apply to institutional investors as business enterprises.

As an investor, how can I be expected to judge what is right?

The UNGPs and the OECD Guidelines do not ask an investor to judge what is right. Rather, they outline an institutional investor’s responsibility to respect internationally recognised human rights.18 These should be understood, at a minimum, as those outlined in the International Bill of Human Rights and the International Labour Organisation’s Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work.

Cultural differences mean different human rights norms, don’t they?

The UNGPs are applicable to all states and business enterprises, regardless of size, sector, location, ownership and structure. Similarly, the OECD Guidelines are a series of non-binding principles and standards for responsible business conduct in a global context consistent with applicable laws and internationally recognised standards. This means that the UNGPs and OECD Guidelines outline what is expected of all businesses, regardless of geography.

The most severe human rights outcomes will, however, vary from country to country.19 This is one of the reasons business enterprises need to carry out due diligence aligned with the UNGPs and OECD Guidelines – by doing so, they can address the most severe actual and potential negative human rights outcomes across different contexts.20

If I invest in companies that create jobs, am I not already making a positive difference?

The financial system is crucial in facilitating economic growth and development. However, positive economic contributions, such as job creation, do not offset the responsibility to manage negative outcomes for people across all investments.

The UNGPs and the OECD Guidelines outline the international responsibility of all business enterprises – including institutional investors – to prevent, mitigate, and address actual and potential negative human rights outcomes. By proactively implementing the UNGPs and OECD Guidelines, businesses can contribute to transformational social and economic change.

What about the positive impacts on human rights delivered by generating returns (e.g. for pensioners)?

Asset owners deliver a variety of social goods, for example through the provision of pensions and life insurance. Investment returns are essential for these provisions. However, such positive contributions do not offset the responsibility to prevent and mitigate actual and potential negative human rights outcomes that may be connected to investments.

The UNGPs and the OECD Guidelines outline the framework through which institutional investors should prevent or mitigate negative human rights outcomes.

As a minority investor, do I have influence?

The OHCHR has outlined that the UNGPs apply to all institutional investors, including minority investors, as echoed by Professor John Ruggie.

Institutional investors, including those that are minority investors, are expected to build and use leverage to change the behaviour of investees.21 Through collaborative engagements and public policy dialogues, among other initiatives, investors can fulfil their responsibility to prevent and mitigate harm to people. Minority investors should not underestimate their leverage, as doing so undermines the drive to garner respect for human rights.

The influence of minority investors was demonstrated in a de facto test case brought against two institutional investors by a group of NGOs. The complaint was related to their minority investment in a controversial Korean steelmaker. The parties eventually reached a joint agreement, with one investor committing to prevent and mitigate harm to people caused by their minority shareholding. It was in response to this case that the OHCHR issued a clarification on the responsibility of minority investors to respect human rights.

As an investor, isn’t my only duty to maximise risk-adjusted returns?

The fiduciary duties of institutional investors include the responsibility to incorporate ESG factors into investment activities. In addition, institutional investors have a responsibility to respect human rights, as set out in the UNGPs and the OECD Guidelines. These duties and responsibilities require investors to act in the best interest of their beneficiaries and deliver good investment outcomes whilst also addressing the negative social outcomes arising from their investment activities.

Around the world, legislation has already moved towards requiring businesses – including institutional investors – to address negative human rights outcomes through appropriate due diligence processes. For example, the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation requires investors to disclose the adverse sustainability impacts of their investment activities, while the French Duty of Vigilance and Dutch Child Labour Due Diligence laws are likely to test that an institutional investor has applied a robust and credible process during the implementation of their fiduciary duties and responsibility to respect human rights.

Additionally, firms in the financial industry are subject to regulation whose focus goes beyond risk and return considerations. For example, in its Code of Ethics and Standards of Professional Conduct, the CFA Institute outlines its global benchmark for investment professionals. This benchmark defines the standards of professional conduct for the integrity of capital markets, duties to clients and conflicts of interest, among others. Investors need to manage their responsibility to meet these standards to ensure the integrity of the financial system.

As an investment manager, shouldn’t I just follow the mandate agreed with the client?

Mandates and legal documentation, such as investment management agreements, define the parameters for how a pool of assets should be invested. ESG considerations are increasingly being included within these – more than two-thirds of PRI asset owner signatories are incorporating ESG requirements into contracts.

Human rights expectations should ideally be defined within these ESG requirements and should be incorporated in the ESG clauses section of the contractual arrangement – the PRI’s appointment guide provides examples of the legal language that can be used.

However, regardless of whether human rights expectations are included within these agreements, investment managers have a responsibility to respect human rights. This responsibility is defined in the OECD Guidelines and the UNGPs and is further clarified in the PRI’s position paper.

Downloads

Why and how investors should act on human rights (English)

PDF, Size 1.17 mbWhy and how investors should act on human rights (Spanish)

PDF, Size 1.18 mbWhy and how investors should act on human rights (Japanese)

PDF, Size 1.43 mbWhy and how investors should act on human rights (French)

PDF, Size 1.05 mb

References

1 https://www.ohchr.org/documents/publications/guidingprinciplesbusinesshr_en.pdf

2 http://mneguidelines.oecd.org/mneguidelines

3 Examples by Shift: https://shiftproject.org/what-we-do/sdgs/

4 See announcements from the European Commission to introduce mandatory corporate environmental and human rights due diligence in 2021

5 In this paper, we use the term “outcome” to refer what the UNGPs call “impact”. For investors, outcomes and impacts are commonly understood as distinct concepts. Outcomes can be intended or unintended, actual or potential, and may be caused by, contributed to or directly linked to the activities of investors. Investors (and particularly impact investors) often define “impact”, as being an actual “change in an outcome caused by an organisation”. See Impact Management Project section on norms.

6 OHCHR (2012): The Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights: An interpretive guide, p. 9-12

7 OHCHR response to Chair of the OECD Working Party on Responsible Business Conduct (2013)

8 A national action plan on business and human rights is a policy strategy to ensure that states adequately protect against negative human rights outcomes for people by business enterprises – see full list on the Danish Institute on Human Rights’ website.

9 See an overview of recent developments at the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre.

10 The OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises also cover environmental issues and economic issues (such as tax).

11 See the PRI Collaboration Platform for historical engagements on social/human rights issues. AUM figures are based on reported information at 2020, rather than at the time of engagement, and may include double counting of overlaps between asset owners’ AUM and their investment managers’.

12 See the PRI Data Portal for reporting by signatories.

13 Activities include both actions and omissions to act

14 Danish Business Authority – Guidance on Responsible Investment (2018), p. 7 (in Danish)

15 The Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action (1993) states human rights globally should be treated “in a fair and equal manner, on the same footing, and with the same emphasis”.

16 https://www.ohchr.org/documents/publications/guidingprinciplesbusinesshr_en.pdf

17 https://www.oecd.org/daf/inv/mne/48004323.pdf

18 The UNGPs define an entity’s responsibility to respect human rights as conducting ongoing, iterative processes that include establishing and embedding a human rights commitment, carrying out human rights due diligence, enabling access to effective remedy, and engaging with affected stakeholders along the way.

19Human rights and business country guides detail the impacts businesses have on human rights across geographies.

20 Based on the UNGPs and OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, the PRI has outlined the steps involved in conducting robust human rights due diligence processes. This includes identifying actual and potential negative outcomes for people arising from investees, preventing and mitigating the actual and potential negative human rights outcomes identified, tracking the ongoing management of human rights outcomes and communicating to clients, beneficiaries, affected stakeholders and the public the outcomes of the actions taken.

21 The UNGPs and OECD Guidelines define leverage as the ability to influence investees and other stakeholders to change the wrongful practices of another party that is causing or contributing to harm.