Responsible investors need decision-useful data to inform their investment process and reporting.

Recent developments in standards, rules and laws regarding corporate sustainability disclosure aim to address these data needs. However, standard setters and regulators often consider responsible investors as a single, homogenous group of financial market participants with common data needs. In practice, responsible investors differ significantly in their needs for data, due to differing objectives, strategies, jurisdictions, etc.

To ensure that these disclosure standards, rules and laws provide decision-useful information to all responsible investors, there is need for a more evidence-based understanding of responsible investors’ data needs. This is particularly timely as standard setters develop more complex issue-specific standards.

This paper sets out the PRI’s Investor Data Needs Framework, which offers a structure to identify decision-useful corporate sustainability data for responsible investors. The purpose of this framework is to ensure that disclosure standards, rules and laws produce decision-useful data that reflects the diversity in data needs among responsible investors.

The Investor Data Needs Framework has been developed by the PRI, with support from Chronos Sustainability, through iterative stages of engagement with signatories, a desk-based review of literature, and engagement with subject experts. This approach was taken to ensure the framework is underpinned by investors’ practice of responsible investment.

What is the framework?

The framework comprises a series of high-level requirements to ensure that data is decision-useful for responsible investors.

What is decision-useful data?

For data to be decision-useful it must be available, of sufficient quality and relevant to either the investment decision-making process (i.e., material) or to investor reporting obligations, or to both.

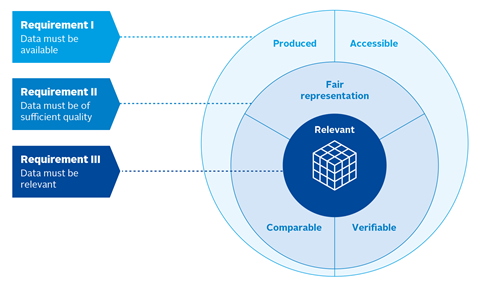

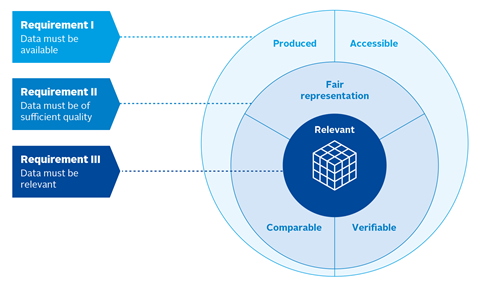

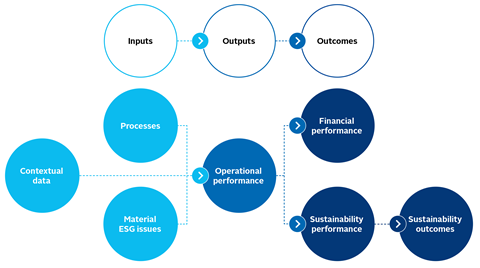

The framework identifies three broad requirements (Figure ES.1):

- Data must be available. It must be: (i) produced, whether as raw data from companies or processed by data service providers; and (ii) accessible to the investor to use in its responsible investment processes.

- Data must be of sufficient quality. It must be: (i) a faithful representation of what the company intends to report; (ii) comparable across multiple dimensions, such as geographies and timeframes; and (iii) verifiable by investors through transparent disclosure and third-party verification of the report, dataset or, in some instances, a specific data point.

- Data must be relevant. This means that it must be relevant for investors’ responsible investment processes or to produce their investment reporting. This is defined using a ‘relevance matrix’, which specifies requirements for data to be decision-useful for investment strategies and responsible investment activities (see box below).

Figure ES.1: Investor Data Needs Framework (overview)

What is the relevance matrix?

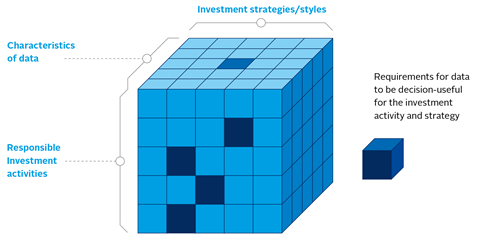

The relevance matrix summarises the set of requirements for data to be decision-useful to responsible investors’ investment process or reporting. It comprises three elements:

- Investment strategies: three of the most frequently used investment strategies – fundamental, quant and passive strategies.

- Responsible investment activities: these 19 investment activities reflect the majority of activities that responsible investors would consider in their investment process and reporting.

- Data characteristics: these define the requirements for the investment activities implemented under each investment strategy and include the type of data (e.g., contextual), the nature of the data (e.g., quantitative), the time horizon of the data (e.g., historic), the granularity of the data (e.g., at the business entity level), whether the data includes information along the value chain, and whether the underlying data points are verified.

As the framework covers most investment strategies and investment activities used by responsible investors, an investor can identify its individual data needs. Likewise, the framework can be applied to identify the data needs for all signatories applying any or all of the investment strategies and responsible investment activities in the framework.

How does the framework work in practice?

The two primary use cases for the Investor Data Needs Framework are:

- To identify data needs: applying the framework to identify a set of requirements for corporate sustainability data for a specific use context – whether for an investment strategy or activity, or for a specific sustainability issue, etc.

- To assess a corporate sustainability disclosure standard, rule or law: applying the framework to assess disclosure requirements using the set of corresponding data needs from Use Case I.

This is not an exhaustive list of applications of the framework but covers those that naturally come from its defined purpose.[1] Note, the framework is not limited to use by the PRI.[2]

The main body of the report outlines the two use cases, including the steps an organisation could follow to implement them, and case studies to illustrate their application.

What is next for the framework?

For the PRI, the next steps for the Investor Data Needs Framework are three-fold:

- Gather feedback on the framework – We will seek feedback from signatories, policy makers, standard setters and other stakeholders on the framework and its application. This period will include at least one workshop or roundtable to gather feedback from PRI signatories and discuss future updates.

- Apply the framework in the PRI’s engagement with standard setters and regulators – The framework will help the PRI understand the breadth of our signatories’ data needs for corporate sustainability data, to further evidence our engagement with standard setters and regulators. In particular, we expect to use the framework to inform our position on forthcoming issue-specific disclosure standards, rules and laws.

- Update the framework – the PRI will release an updated report on the Investor Data Needs Framework, based on feedback, lessons learnt and expansions to the framework (e.g., to new data sources). In particular, the update will look to address a gap in the current framework by identifying what responsible investment activities investors most frequently implement on different issues. This will help standard setters and regulators develop a sense of what data is most important for responsible investors today and in the future.

Introduction

‘Driving meaningful data throughout markets’ is a key PRI Blueprint target. It enables the flow of high-quality decision-useful data from companies through the investment chain to inform asset owners’ and investment managers’ implementation of their responsible investment practices. However, investors regularly complain to the PRI about a lack of decision-useful corporate sustainability data.

As the world’s leading proponent of responsible investment, the PRI advocates for globally comparable and decision-useful corporate sustainability disclosure. The PRI is therefore working with its global network of over 5,000 signatories to ensure that developments in sustainability standard setting and rulemaking (see Box 1) enable globally comparable and decision-useful corporate sustainability disclosures.

Box 1: Developments in sustainability standard setting and rulemaking

Sustainability disclosure by companies is driven by a number of internal and external factors, including, respectively, corporate governance and developments in corporate sustainability disclosure standards, rules and laws. Historically, there have been few mandatory requirements,[3] and most corporate sustainability disclosures have been made using voluntary frameworks.[4] However, in recent years, the number of mandatory disclosure requirements has grown, with the establishment of the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) by the IFRS Foundation in 2022 and significant developments across jurisdictions such as the EU and the US.

These draft standards, rules and laws will, once implemented, significantly expand the scope and granularity of mandatory sustainability-related disclosures. They can broadly be split into general sustainability disclosure requirements and those focused on specific issues.

| General sustainability draft standards include: | Issue-specific draft standards include: |

|---|---|

|

|

Corporate sustainability disclosure standards, rules and laws are designed to meet the needs of investors, who make up one of the primary groups of users of the disclosures. However, standard setters and regulators often consider responsible investors as a single, homogenous group of financial market participants with common data needs. This assumption is intended to ensure that disclosure meets the minimum needs of a wide group of investors and to limit the level of complexity in disclosure requirements.

However, in practice, there is little homogeneity in responsible investors’ data needs. For example, we see significant variation in data needs among the PRI’s signatory base, driven by factors such as signatories’ objectives, strategies, fund size, jurisdiction, the asset classes in which they invest, sustainability issues of interest and their own disclosure requirements, to name a few.[5]

Therefore, as standards, rules and laws on corporate sustainability continue to develop, there is need for a more evidence-based understanding of responsible investors’ data needs. This is particularly timely as standard setters and regulators develop more complex issue-specific disclosure standards, rules and laws.[6]

This paper sets out the PRI’s Investor Data Needs Framework, which is a structure to identify decision-useful corporate sustainability data for responsible investors. The purpose of the framework is to ensure that disclosure standards, rules and laws produce decision-useful data that reflects the diversity of needs for data across responsible investors.

The paper builds on the insights of previous research and thought leadership by the PRI on sustainability reporting, namely the discussion paper by the PRI and the International Corporate Governance Network on Corporate ESG Reporting and the report by the PRI on its Driving Meaningful Data (DMD) Framework.

Although the DMD Framework recognised that corporate disclosure and investor reporting are both key components of an ‘end-to-end’ reporting system, this paper focuses only on the role of corporate disclosure. This paper considers investor reporting in defining investors’ data needs, rather than the potential implications of the Investor Data Needs Framework for investor reporting (see Box 2).

Box 2: The complex link between investor data needs and investor reporting

The DMD Framework envisioned an ‘end-to-end’ sustainability reporting system as one “which cohesively characterises how entities are managing sustainability risks and opportunities, and how their actions and activities shape or contribute towards sustainability outcomes”. This broad concept envisages a consistent flow: from data to inform investment decision-making (which includes corporate disclosure) to investors’ reporting.

However, historically this link has not been clear-cut. Investors’ reporting, whether mandatory or voluntary, has focused on reporting on their objectives and internal processes (e.g., reporting on internal governance processes to assess ESG).[7] This type of reporting – also referred to as ‘tell-me’ reporting – does not rely on data regarding the specific investees.

More recently, investor reporting has been shifting towards ‘show-me’ reporting. In contrast to the tell me approach, it requires reporting on the results and outputs of investors’ processes. These might include the number of proxy votes, or changes to their sustainability performance, for example their portfolio carbon footprint or contribution to wider sustainability goals. As a result, this type of reporting is more heavily dependent on aggregated data from investees, aggregated to the level of financial product, asset class or investment entity.

In line with this trend, the PRI has been expanding the show-me reporting requirements of its Reporting and Assessment (R&A) Framework for signatories,[8] most recently in relation to investors’ sustainability outcomes.[9] This show-me reporting complements the ongoing reporting requirements on investors’ objectives and processes.

As a result, the relevance of the Investor Data Needs Framework to investor reporting is, for now, limited. This paper only considers investor reporting as one of the activities that informs the data needs of investors (see Responsible Investment Activities). As the data requirements of investor reporting – including the PRI’s R&A Framework – continue to evolve, we will continue to assess the interaction between those data needs, the data to inform investment decision-making, and the application of the Investor Data Needs Framework.

The rest of this report is structured as follows:

- Approach outlines the scope of the framework, and our approach to developing it;

- Investor Data Needs Framework summarises the requirements that underpin it;

- Application of the framework outlines the two primary use cases for the framework, illustrated with case studies; and

- Next steps sets out how the PRI will engage on the framework, implement the framework in its engagement with standard setters and regulators, and expand it in future.

This is accompanied by three appendices and a glossary of terms.

Approach

The Investor Data Needs Framework has been developed by the PRI, with support from Chronos Sustainability, a specialist advisory firm.

The scope of the framework was dictated by the breadth of our signatories’ data needs. As a result, the framework must be applicable to responsible investors, irrespective of their objectives and strategies, the sustainability-related issues they focus on, the asset classes they invest in[10] and the jurisdictions they operate in.

The framework must also be granular enough to look at specific data needs, such that it can be applied to a specific sustainability issue or by a group of investors (for example, those focused on a specific asset class or operating in a particular jurisdiction).

As set out in Figure 1, the framework was developed through iterative stages of engagement with signatories, a desk-based literature review and consultation with subject experts.

Figure 1: Project approach

| Engagement with signatories | Desk-based review | Engagement with subject experts |

|---|---|---|

|

Extensive engagement with 30 signatories through:

|

Review of literature on:

|

Engagement with experts from:

|

*For part of the online survey, we asked signatories to respond across broad product ‘types’.[11]

Engagement with signatories was at the core of developing the framework. This included a diverse group of asset owner, investment manager and service provider signatories, operating in different regions, with different fund sizes, investment strategies, asset class focus, etc.[12] Most of the signatories are members of the PRI’s Corporate Reporting Reference Group.

The approach means that the framework is underpinned by the real-world practice of responsible investment and, where possible, it builds on established concepts.

The Investor Data Needs Framework

The Investor Data Needs Framework provides a structure to identify decision-useful data. It does this by specifying a series of high-level requirements for data to ensure that it is decision-useful for most responsible investors.

The framework is developed on the basis that, for data to be decision-useful to an individual investor, it must be available, of sufficient quality and relevant to either the investment decision-making process (i.e., material) or to investor reporting obligations, or to both. This is reflected in the three broad requirements (I-III) of the framework (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Investor Data Needs Framework (overview)

The framework adopts a wide definition of corporate sustainability data, in terms of what it means by data and the channels whereby data is transmitted to investors’ data infrastructure[13] (Box 3).

Box 3: Corporate sustainability data

The framework’s definition of corporate sustainability data does not distinguish between:

- a single datapoint or a dataset. Data could be a single data point (whether an individual metric, indicator or string of text) or a wider dataset (i.e., more than one metric, indicator or string). Note that even when we refer to a single datapoint, there may be multiple pieces of information or metadata within the ‘point’;

- the characteristics of the data, including whether quantitative or qualitative, the time horizon, the scale of the data etc.; and

- different sources of corporate data. See Requirement I for more information.

This definition of corporate sustainability data is agnostic of corporate definitions of ‘materiality’ (financial, impact, dynamic, etc.) as materiality for investors depends entirely on what is relevant to them. See Requirement III of the framework.

The following sections outline the three broad (and respective specific) requirements for corporate sustainability data to be decision-useful for a responsible investor.

Requirement I: Data must be available

Data must be available in order for it to be used in an individual investor’s responsible investment process or disclosure. Availability has two specific requirements: data must be produced and be accessible.[14]

Data must be produced

Corporate sustainability data can be produced via different channels, which are broadly organised into:

- raw data from companies, whether from public disclosure (e.g., financial accounts, integrated reports or sustainability reports),[15] investors’ requests or via data service providers who collect this from public disclosure or their own written requests or questionnaires; and

- data processed by a data service provider, including estimated data,[16] derived data,[17] and scores or ratings.[18]

Where the raw data that investors need is not produced by companies, investors can engage with them to encourage them to provide this data, taking due account of the feasibility of disclosing it.[19] Where raw data is not produced, but investors still require the data, they will then rely on data processed by a data service provider – particularly estimated data and ratings or scores.

If the data is considered material to the individual investor’s decision-making, its absence (whether raw or processed) could prevent new investments or result in divestment from a company. Box 4 outlines different approaches that investors in private markets undertake to overcome this barrier.

Box 4: Approaches to tackle limited data in private markets

The production of data is an acute issue in private markets, where companies are typically not required by regulators or stock exchanges to disclose information to the same extent as their listed peers. In two specific investment contexts, signatories took the following approaches to tackle this gap:

- Early-stage investments: For investors’ due diligence of early-stage investees, data does not usually exist and it is not feasible for investees to produce it. Investors instead must rely on proxies. For example, one signatory said it profiles company management as a proxy for preparedness and action.

- Later-stage investments – with control: Data is not produced, so fund managers (limited partners, or LPs) work with their investors (general partners, or GPs) to collect this data during due diligence processes and to create procedures for data production for regular disclosure. The latter approach is particularly likely when GPs are contractually required to report data to LPs.

GPs may go a step further and require that investee companies collect additional data as a condition for investment.

Note, if a GP does not exert control over an investee, or if the GP is not required to collect the data, it may not be possible for investors (especially LPs) to access that data, even if it is produced by the investee. In certain situations, investors in private markets may not have any corporate data. For example, a fund of funds operating in the secondary market may need to focus on determining the profile and track record of the GP it is investing through, rather than that of all the (numerous) underlying investments.

Data must be accessible

Accessibility refers to whether data is in a format that the individual investor can easily input into its data infrastructure and use in its responsible investment process and reporting.

There is no consensus on the exact format that data should follow, as each investor’s infrastructure will differ, but overall expectations are that the data should at least be digital and include metadata (including tags). As data can, if required, be reformatted to meet an investor’s exact requirements, the format in which data is supplied does not present a barrier to its use; it can, however, make that use more difficult and time consuming.

Signatories noted that accessibility was also a function of factors outside of corporate data, including: the size of the investor’s portfolio compared with its available resources (such as the number of analysts); its investment strategy; and the state of its data infrastructure (Box 5).

Box 5: Accessible data infrastructure

Signatories observed that ensuring that data can be used in asset owners’ and investment managers’ data infrastructure is an important step in integrating decisions on responsible investment into wider investment decision making. However, the accessibility of the data format is only one element of what investors need to do to ensure this data is available to their decision-makers (such as portfolio managers), especially when investors operate over multiple jurisdictions.

One signatory noted that accessibility depends on the integration of its different platforms into its data infrastructure – referred to as a ‘data lake’. For example, if its portfolio managers and analysts are working across multiple platforms to find data or record engagements, it disincentivises the use of additional data in the investment process.

Requirement II: Data must be of sufficient quality

The available data must be of sufficient quality to inform individual investors’ responsible investment process or reporting.

The clearest benchmark to assess whether information is of sufficient quality for financial market participants is the qualitative characteristics of useful information defined by the IFRS Foundation’s Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting. An assessment of the six characteristics of the Conceptual Framework identified faithful representation, comparability and verifiability as specific requirements for data to be of sufficient quality (see Appendix 1 for a mapping of all six IFRS characteristics to the Investor Data Needs Framework). As illustrated in the appendix, these same characteristics are also central to recognised draft standards on sustainability disclosure and recent literature on investors’ data needs.

These three specific requirements are outlined in the sections that follow. Their descriptions build on the terminology used by the IFRS and the draft sustainability standards,[20] updating them to focus on the specific needs of asset owners and investment managers.[21] These requirements are interrelated and their relative importance will depend on the individual investor’s requirements for its investment processes or reporting (Box 6).

Box 6: Relative importance of comparability

One signatory noted that an investor’s investment strategy may determine the relative importance of comparability. It highlighted that, where the strategy is passive or quant, comparability would be more important than if a fundamental strategy were in use. In contrast to the first two strategies, the signatory noted that, for a fundamental strategy, more importance is placed on the company’s future performance than the comparability of the company’s data with that of its peers.

Data must be a faithful representation

The data should, to the extent possible: (i) include all material data necessary for the user to understand the risks, opportunities and impacts, where relevant; (ii) be unbiased in the selection of this data; and (iii) be free from error.

Data must be comparable across multiple dimensions

The data should be consistent across multiple dimensions for investors to identify and understand similarities or differences across their portfolio. Dimensions that investors may consider include consistency across individual investees or business entities, asset classes, sectors, geographies and timeframes.

Data must be verifiable by investors

Investors should be able to corroborate the data, or identify the underlying data used to derive it. Corroboration for an individual investor could be a combination of one or more of the following:

- transparency of the underlying processes, metrics and methodologies. This is the very least that investors would expect from data;

- third-party verification for a dataset (e.g., assurance of a report). Assurance of a dataset or report should, according to the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO),[22] also include: (i) clarity on which sustainability information has been assured; (ii) the scope of assurance conducted; and (iii) conclusions reached;[23] and

- verification by a third-party for a specific data point (e.g., emissions data), which will depend on the relevance of the data. This is outlined below, under Requirement III.

Requirement III: Data must be relevant

For data to be relevant, it must meet the specific requirements for the investor’s activities in its responsible investment process and to produce its reporting.[24][25] The framework refers to these tasks as ‘responsible investment activities’.

Identifying the specific requirements for the investor’s responsible investment activities is complex, given differences among investors in what activities they implement and how these activities are implemented. For example, of the 51 (broad) financial product types identified in the survey, only a handful overlapped in the exact list of activities they applied. To tackle this, the specific requirements for relevance are defined as: ‘the requirements for data to be decision-useful for an investor’s set of investment strategy and investment activities’. The three elements of defining these requirements are set out in the sections that follow.

Investment strategy

Investors use the term ‘investment strategy’ (or ‘style’) in a variety of ways.[26] Within the framework, this term refers to the process that structures investors’ implementation of their responsible investment activities. Engagement with signatories found that this is a useful structure to group investors’ data needs, as it plays an important role in determining what activities investors select and how they implement these activities.

Based on signatory feedback, we have prioritised three broad investment strategies,[27] which were identified most frequently by signatories surveyed, whether applied in isolation or in combination:[28]

- fundamental strategies, where the investment decision is based on human judgement. This includes both bottom-up (e.g., stock-picking) and top-down (e.g., sector-based) strategies;

- quant strategies or funds, where the manager builds computer-based models to determine whether an investment is attractive. In a pure quant model, the model makes the final decision to buy or sell; and

- passive strategies that mirror the performance of an index and follow predetermined buy-and-hold strategies that do not involve active forecasting. These include smart beta strategies,[29] investments in broad capital market indexes, ESG-weighted indexes, themed indexes, passively managed exchange-traded funds, etc.

Signatories said that, in general, the largest set of requirements for data are for fundamental strategies, followed by a subset for quant strategies and then finally passive strategies. Although these investment strategies are more often associated with listed equities,[30] feedback from signatories suggested that they are also generally applicable to other asset classes.

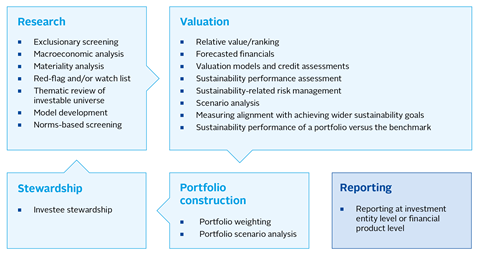

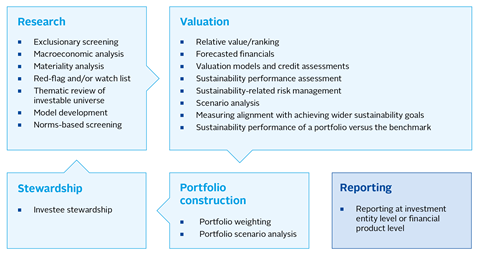

Responsible investment activities

The framework specifies 19 investment activities that cover the four broad areas of the responsible investment process – research, valuation, portfolio construction and stewardship – and investor reporting (see Figure 3). This provides a globally applicable list for all asset classes within the scope of the framework.[31]

Figure 3: List of responsible investment activities

See the Glossary for definitions of each activity, which adopts or builds on established terminology.[32] Note, the investment process is simplified to be depicted as unidirectional, but in reality could be iterative and all four broad areas could inform reporting.

Signatories consulted on the framework confirmed that this list captures the breadth of activities they would consider when implementing their responsible investment process and reporting. They recognised that not all activities would be applicable to every individual investor and there may naturally be overlaps in the specific requirements of some of the activities. However, this overlap is by design, and represents the nuances in approach across responsible investors.

Data characteristics

Finally, the characteristics of the data define the requirements for the investment activities implemented under each investment strategy.

The primary characteristic is the type of data required to inform each activity. The engagement and evidence review suggests that investors need a combination of different types of data (Figure 4),[33] grouped as follows:

- ‘inputs’ refer to data on the context (e.g., location and sector), the company’s processes (including governance, strategy and risk management processes) and the material ESG issues which will be identified through the company’s (or investor’s) materiality assessment;

- ‘outputs’ measure the company’s operational performance, including its production, number of staff, etc.; and

- ‘outcomes’ measure the effects of the operational performance on the business’s financial performance and on people, planet and the economy. The latter may measure sustainability performance (e.g., emissions) or performance may be measured in the context of global sustainability goals and thresholds (i.e., sustainability outcomes).

Figure 4: Types of data

See the Glossary for definitions of each type of data.

Other secondary characteristics that define the data are:

- the nature of the data, whether it is: quantitative and an absolute value or a relative value; quantitative and a score or rating; qualitative and pre-defined (including a binary measure); or open-ended (like a narrative or a case study);

- the time horizon of the data, including whether the data is: historic and informs investors’ assessment of trends; a measure of the current position of the company (i.e., a point in time); or forward-looking, whether measured as a point in time or a change;

- its granularity, which ranges in scale from measurement at the portfolio level down to the asset or economic activity level;[34]

- whether it includes information along the value chain, particularly where this refers to a company’s direct customers and suppliers;[35] and

- whether the underlying data points are verified. This specifies whether the third-party verification under Requirement II is needed for a specific data point to input into the activity.

It should be noted that, just as the requirements for each activity are defined by these data characteristics, the data point or set must also be defined along these same characteristics in order to assess whether the data is decision-useful.

Relevance matrix

The three elements of relevance (investment strategy, responsible investment activities and data characteristics) together define the set of specific requirements for data to be relevant to an investor’s responsible investment process or reporting, or both.

This set of requirements is illustrated by a relevance matrix (Figure 5), where each cell (or box) represents the requirements that data must meet to be decision-useful for an investment activity or investment strategy.

Figure 5: Illustrative example of an investor’s relevance matrix

As each investor is unique in its set of investment strategies, activities and specific data characteristics, what it considers as relevant will also be unique and represented by its own relevance matrix. Appendix 2 outlines key criteria an investor should consider when specifying its own matrix.

Application of the framework

There are two primary use cases for the Investor Data Needs Framework:

- To identify data needs. Investors can apply the framework to identify a set of requirements for corporate sustainability data for a specific use context – whether for an investment strategy or activity, or for a specific sustainability issue, etc.

- To assess a corporate sustainability disclosure standard, rule or law. Investors can apply the framework to assess disclosure requirements using the set of corresponding data needs from Use Case I.

This is not an exhaustive list of applications of the framework, but ones that naturally come from its defined purpose. Other use cases could include applying the framework to: identify gaps in the current data landscape (including estimated data, derived data and scores or ratings); assess other data sources (e.g., NGO data); and assess other sources of disclosure requirements (e.g., guidance documents by initiatives). For more information on how these applications will be approached in the future, see the Next Steps section.

The framework is also not limited to use by the PRI, as it is being made public so that different stakeholders can apply it. In particular:

- Standard setters and regulators could use it to inform the development of decision-useful disclosure standards, rules and laws.

- The PRI could apply it to understand the breadth of signatories’ data needs regarding corporate sustainability data, and to further evidence its engagement with standards setters and regulators.

- Individual responsible investors or investor groups could use it to structure their engagement on corporate sustainability data (whether with standards setters and regulators or directly with companies); and

- Companies could use the framework to prioritise what data is most important for its investors.

The following sections outline the two use cases, including the steps any organisation could follow to implement them, and case studies to illustrate their application.

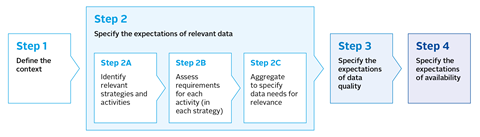

Identify data needs

This process involves four steps (Figure 6), beginning by specifying the context of the data needs (Step 1) before working from the centre of the framework out (i.e., from relevance to availability), to define the expectations for each of the requirements (Steps 2-4).

Figure 6: Steps to identify data needs

In Step 1, the context is defined by:

- The scope of investors for whom the data needs will be assessed. This is defined by the set of investment strategies, activities and other features of the investors (e.g., jurisdiction and asset class). For example, it could be defined for investors applying a specific investment strategy, those in a specific jurisdiction, or the responsible investment community as a whole.

- The scope of the data to be assessed and whether the data needs are for general disclosure requirements or focus on a specific issue (e.g., human rights).

Steps 2-4 apply the requirements from the framework to the context defined in Step 1. This is best illustrated through the following case studies:

- General data needs: this applies the framework to identify general data needs for all investment strategies and responsible investment activities in the framework;

Case study: General data needs

General data needs for investors refer to the minimum requirements for corporate sustainability disclosure standards, rules or laws that cover the needs of the majority of PRI signatories’ responsible investment strategies.

Step 1: Specify the context

The framework is applied to identify the data needs for all signatories implementing any of the investment strategies and responsible investment activities in the framework for general corporate sustainability disclosure requirements.

Step 2: Specify the expectations of relevant data

Relevance requires data to be decision-useful for the different investment strategies and activities adopted by PRI signatories. This means that all investment strategies and activities in the relevance matrix need to be considered (Step 2A).

As signatories differ in how they implement each investment activity (i.e., the specific requirements to implement these activities), the common denominator across the signatories is defined by the minimum characteristics of data to implement those activities (Step 2B). (See Box 7 for more clarity on how the framework defines minimum requirements.) The full set of requirements in the relevance matrix are set out in Appendix 3.

Box 7: Defining the minimum requirements

The framework’s minimum requirements have been defined using the PRI’s current guidance for responsible investment,[36] guidance from the PRI and the CFA Institute,[37] and expert input. It is important to recognise that this minimum is a snapshot of current expectations to implement responsible investment activities, which are likely to evolve over time. We will aim to update the framework in line with the PRI’s guidance for responsible investment as it evolves.

When data needs are applied across investment strategies, with no constraints on the scope of investors (e.g., whether by jurisdiction or asset class) then the minimum requirements should be the default set of requirements.

Table 1 summarises the results of aggregating the minimum requirements across investment strategies and activities (Step 2C). The table aggregates these expectations from the insights identified using the results across the relevance matrix on minimum requirements, set out in Appendix 3. This is organised into two dimensions, which correspond with the format required to assess disclosure standards, rules and laws on a principles basis, and for specific disclosure requirements within the standard, rule or law.

Table 1: Expectations for relevant data

| Insights from across the Relevance matrix | Expectations for the principles of the disclosure requirements | Expectations for a specific disclosure requirement within the standard |

|---|---|---|

|

All activities require at least two data types (irrespective of strategy) and the majority require more than five different data types (particularly for fundamental strategies). |

Datasets should capture the breadth of data types, which include inputs (e.g., context), outputs (operational performance) and outcomes (e.g., sustainability performance). |

N/A |

|

The majority of activities require contextual data. |

Datasets should include contextual information. |

N/A |

|

The required granularity of data across almost all the activities is at business entity level. Investment activities where this is not the case require country-, sector- or portfolio-level data, which can be aggregated from business entity-level data. |

Datasets should include data at least at business entity level. |

Data points should be reported at least at business entity level and be easy to aggregate. However, more granular, activity-level information may be required with the increasing application of activity-based taxonomies, which will, in turn, influence investors’ data needs. |

|

The required time horizon of data varies across activities – whether focused on a specific activity or referring to a combination of current, historic and forward-looking data. |

Datasets should not focus on only one time horizon. |

Data points should be clear about the time horizon they refer to. |

|

Almost all activities require quantitative data and/or pre-defined qualitative metrics. |

Datasets should at least include quantitative and pre-defined qualitative metrics. |

Quantitative and pre-defined qualitative data points should be clearly defined and standardised. |

|

Some activities require qualitative data as the only type, or one of many.[38] |

Datasets may need qualitative data to address specific data types (e.g., on process, about the corporate strategy) or to explain the quantitative data (e.g., for changes). |

Qualitative data should be informative either as an independent data point (e.g., on governance) or clearly explain quantitative data (e.g., for changes). |

|

Some activities require data to include information on the value chain. |

Datasets should be clear about their reporting boundaries. |

Data points should clearly specify the operational boundaries, irrespective of whether the data refers to a parent company, group or company’s value chain. |

Step 3: Specify expectations for data quality

Expectations for data quality are defined by the requirements that data must be a fair representation of what the company intends to report, comparable and verifiable. Looking across the investment strategies and activities, it is assumed that all three requirements will be equally important.

Table 2 summarises expectations, based on minimum requirements for data to be of sufficient quality.

Table 2: Expectations for data quality

| Specific requirements | Expectations for the principles of the disclosure requirements | Expectations for a specific disclosure requirement within the standard |

|---|---|---|

|

Fair representation |

|

|

|

Comparable |

||

|

Verifiable

|

Step 4: Specify expectations for availability

Expectations for data quality are defined by the specific requirements that data must be produced and accessible. Table 3 summarises expectations based on minimum requirements for data to be available. Note, if the application of the resulting data needs is to assess a standard, rule or law, then production is no longer relevant, because those standards, etc. provide a channel within which data is produced.

Table 3: Expectations for data availability

| Specific requirements | Expectations for the principles of the disclosure requirements | Expectations for a specific disclosure requirement within the standard |

|---|---|---|

|

Production |

|

N/A |

|

Accessible |

|

N/A |

- Human rights data needs for norms-based screening: this illustrates the application of the framework to human rights using a specific activity, norms-based screening, for all investment strategies;

Case study: Human rights data needs for norms-based screening

This case study identifies the human rights data needs for norms-based screening, for any investment strategy.

Step 1: Specify the context

The framework is applied to identify the data needs of all signatories applying any investment strategy in the framework to norms-based screening for human rights data from corporate sustainability disclosure.

Step 2: Specify the expectations of relevant data

The case study is applicable to all investment strategies in the framework, but it focuses on norms-based screening (Step 2A).

According to the PRI’s Reporting and Assessment framework, norms-based screening refers to “screening investments against minimum standards of business practice based on international norms.” Widely recognised standards include UN treaties, Security Council sanctions, the UN Global Compact, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and OECD guidelines.

Issue-specific requirements here are defined by combining the minimum requirements to implement norms-based screening (irrespective of the issue)[40] with requirements for human rights.

Minimum requirements

The minimum requirements are defined by how the activity is implemented in practice (Box 8). The table on Research in Appendix 3 specifies the minimum requirements for norms-based screening across the three investment strategies. As all three investment strategies require the same data characteristics, the minimum requirements across the investment strategies are equivalent.

Box 8: Norms-based screening in practice

Investors implement norms-based screening to identify and adjust their investable universe by assessing whether investees meet international ‘norms’. As a responsible investment activity, it falls under the broad area of Research, which approximately 40% of PRI signatories indicated that they undertake.[41]

In practice, investors can apply this in two ways:

- By excluding companies: As set out in the PRI’s introductory guidance on screening,[42] this would normally involve excluding investments for any failure to meet accepted norms, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

By including companies: Although significant breaches to international norms are not acceptable to most investors, there are instances where infractions may not be clear-cut and investors may see an opportunity to identify specific investees for stewardship activities.[43][44]

Application to human rights

For human rights, the minimum standards of business practice required to inform screening are defined by the following international norms: The International Bill of Human Rights; the Declaration of the International Labour Organization (ILO) on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work; the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises; and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs).

These specify the minimum requirements, defining: (i) the universe of rights that companies need to cover in the approach (i.e., the ‘what’), as per the International Bill and the ILO Declaration; and (ii) the policies and processes that companies are expected to adopt to ensure respect for human rights (i.e., the ‘how’), with reference to the OECD Guidelines and the UNGPs. The resulting set of requirements for norms-based screening refers to monitoring whether corporates’ responsibilities to respect human rights are being met.

These can be summarised into the following broad requirements (with the relevant UN Guiding Principles in brackets):[45]

- Embed a commitment to respect human rights into policies and procedures (Principle 16);

- Identify and assess adverse human rights outcomes (Principles 17 and 18);

- Take action to cease, prevent and mitigate these outcomes (Principles 19 and 23);

- Track to ensure effective implementation of these actions (Principle 20);

- Communicate outcomes (Principle 21); and

- Remediate those affected by the outcomes (Principles 22 and 24).

(For more information about the high-level requirements for human rights data, irrespective of investment activity, see Box 9.)

Box 9: Managing human rights risks: what data do investors need?

The PRI launched a research project in 2022 to understand investor data needs and challenges regarding human rights. The project was undertaken with the US not-for-profit organisation Shift, which interviewed 15 global investors leading research and engagement on human rights and two data providers.

The report, published in November 2022, found that investors across regions and types of organisations generally need four categories of information on human rights to implement their responsible investment activities: (1) business model risks; (2) leadership and governance; (3) due diligence procedures; and (4) positive human rights outcomes. In terms of the sources of this data, signatories said they not only rely on corporate disclosure, but also use a variety of other sources of information, including civil society groups and human rights organisations. In some instances, they contacted affected stakeholders directly for on-the-ground information about corporate practices vis-à-vis human rights and social issues.

For more information, see the PRI’s discussion paper, What data do investors need to manage human rights risks?

Issue-specific requirements

Table 6 combines minimum requirements with additional requirements for human rights for norms-based screening. The combined results are set out in the column on Issue-specific requirements (Step 2B). The final column provides additional notes on the specific requirements for human rights.

In practice, this same assessment would be undertaken for each investment activity (Step 2C). The aggregate issue-specific data requirements (and comments) will then specify the full set of expectations for relevant data for human rights.

Step 3: Specify the expectations of data quality

These are defined by the expectations set out for general data needs on data quality, above.

The only requirement that might be expanded for human rights is on verification. International norms may require verification of specific data points by a third-party. However, this is extrapolated from the assessment of norms-based screening, and would require the full application of the Investor Data Needs Framework to be definitively included as an expectation.

Step 4: Specify the expectations for availability

These are defined by the expectations set out for general data needs on availability, above.

For additional commentary on the whether the human rights data needs identified in Table 4 can be met in practice, please see Box 10.

Box 10: Availability of data to meet human rights data needs

Some of the data needs listed in Table 4 may already be met by companies that follow the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) sustainability disclosure framework (in particular GRI 2, GRI 3 and GRI 204[46]) or data reported by the World Benchmarking Alliance’s Social Transformation Benchmark on companies.[47]

However, not all data required on human rights is likely to be produced by companies, and interested investors currently have to rely on other sources like the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre’s Allegation database, the OECD National Contact Point procedure and court cases on human rights issues, or data processed by data providers that integrate this information (e.g., through scores or ratings).

Table 4: Issue-specific data needs – norms-based screening on human rights

| Data characteristics | Minimum requirements* | Issue-specific requirements | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Type of data |

Contextual data |

Include contextual datapoints on the location of the company (sites, operations, etc.) and laws applicable to the company, as well as recognition of internationally recognised human rights. |

||

|

Material ESG issues |

||||

|

Processes |

Governance data on the policies and procedures in place to: (i) embed a commitment to respect human rights; (ii) identify and assess adverse impacts; (iii) take actions to cease, prevent and mitigate adverse impacts; and (iv) inform remediation processes, including whether the company has a grievance mechanism. |

|||

|

Operational performance |

||||

|

Financial performance |

||||

|

Sustainability performance |

Data on: (i) involvement in significant controversies, especially those with unsatisfactory resolutions; (ii) remediation actions undertaken; and (iii) how the company has communicated the adverse impacts. |

|||

|

Sustainability outcomes |

Data to track the effectiveness of the implementation. |

|||

|

Nature of data |

Quantitative indicator – absolute/relative value |

|||

|

Quantitative indicator – score/rating |

Ratings/scores from third-party providers are often used by investors for norms-based screening. |

|||

|

Qualitative – pre-defined |

||||

|

Qualitative – open (inc. case studies) |

||||

|

Time horizon |

Historic – trends |

|||

|

Current – point in time |

||||

|

Forward-looking – point in time/change |

||||

|

Granularity |

Portfolio level |

|||

|

Sector/geographic level |

||||

|

Business entity level |

||||

|

Asset or economic activity level |

||||

|

Value chain data |

The UN Guiding Principles highlight the need to consider the value chain. |

|||

|

Verification of underlying data |

The underlying data must be assured for human rights. |

|||

| Requirements for specific data characteristics |

*See Appendix 3.

- Climate change data needs for forecasted financials: this illustrates the application of the framework to climate change using a specific activity, forecasted financials, for all investment strategies.

Case study: Climate change data needs for forecasted financials

This case study identifies the climate change data needs for forecasted financials, across all investment strategies.

Step 1: Specify the context

The framework is applied to identify the data needs for all signatories, applying any of the investment strategy in the framework, to forecasted financials for climate change data from corporate sustainability disclosure.

Step 2: Specify the expectations of relevant data

The case study is applicable to all investment strategies in the framework but focuses on forecasted financials (Step 2A).

Forecasted financials refers to the process of estimating and/or adjusting forecasted financials (e.g., revenue, operating costs, asset book value or capital expenditure) and financial ratios. These may then be used in valuation models or credit assessments.[48]

The issue-specific requirements to implement forecasted financials to climate change are defined by combining the minimum requirements to implement forecasted financials (irrespective of the issue),[49] then adding requirements for climate change.

Minimum requirements

The minimum requirements are defined by how the activity is implemented in practice (see Box 11). The table on Valuation in Appendix 3 specifies the minimum requirements across the three investment strategies in the framework. For this activity, the quant and passive strategies require subsets of the data characteristics of fundamental strategies, so the minimum requirements across the three investment strategies rely on those for fundamental strategy.

Box 11: Forecasted financials in practice

As set out in the PRI’s ESG integration in listed equity: A technical guide, forecasting financials could involve forecasting revenue, operating costs, asset book value, capital expenditure, etc., which would then be used to inform valuation models and credit assessment.

Application to climate change

For climate change analysis, forecasting the risks and opportunities to an investee is defined by a company’s:

- exposure to factors external to its business, such as the natural environment, the macroeconomy, customer sentiment, etc.

- commitments, such as to achieve net zero emissions by a certain date.

- contextual information, such as its sector, region or jurisdiction, given that decarbonisation pathways are often sector-, region- or jurisdiction-specific.

In addition, the forecasting may also be defined by an investor’s requirements to assess and manage its climate risk with scenario analysis, as set out by, for example, the PRI’s R&A Framework, the Task Force for Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), the Investor Climate Action Plan Expectation Ladder, and the Paris Aligned Investment Initiative’s Net Zero Investment Framework. Combined with the earlier point on corporate commitments and contexts, an additional requirement is to include data on sustainability outcomes. This will be explored further in future PRI work.

Identify data needs

Table 5 combines the minimum requirements with the additional requirements for climate change on forecasted financials; the combined results are reported in the column on issue-specific requirements (Step 2B). The final column provides additional notes on the specific requirements for climate change.

Table 5: Issue-specific data needs – forecasted financials on climate change

| Data characteristics | Minimum requirements* | Issue-specific requirements | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Type of data |

Contextual data |

On the company’s location, sector and, where applicable, its commitments. |

||

|

Material ESG issues |

||||

|

Processes |

On the policies and procedures in place to assess the quality of climate change governance and strategy as well as the alignment of the company’s strategy with its commitments. |

|||

|

Operational performance |

On the production, given the inherent link to financial performance. Also on, where relevant, fossil fuel exposure (e.g., fossil fuel reserves). |

|||

|

Financial performance |

On the financial exposure due to climate change accounted for in the income statement and on the balance sheet, as well as the expected financial exposure from climate analysis (on emissions and scenario analysis), which may not be accounted for in the financial statements. |

|||

|

Sustainability performance |

Sustainability performance data on the company’s current climate change position based on Scope 1, 2 and 3 data. Its forward-looking climate change position, based on scenario analysis and future emission estimates. |

|||

|

Sustainability outcomes |

Where investors have made a net zero commitment, sustainability outcomes data on the company’s alignment with net zero commitments is also required. |

|||

|

Nature of data |

Quantitative indicator – absolute/relative value |

Quantitative information on the sustainability performance. |

||

|

Quantitative indicator – score/rating |

||||

|

Qualitative – pre-defined |

||||

|

Qualitative – open (inc. case studies) |

Quantitative data may need to be complemented with qualitative data on governance and strategy. |

|||

|

Time horizon |

Historic – trends |

|||

|

Current – point in time |

||||

|

Forward-looking – point in time/change |

||||

|

Granularity |

Portfolio level |

|||

|

Sector/geographic level |

||||

|

Business entity level |

||||

|

Asset or economic activity level |

||||

|

Value chain data |

Scope 3 emissions play an important role in estimating the company’s climate risks. |

|||

|

Verification of underlying data |

||||

| Requirements for specific data characteristics |

*See Appendix 3.

In practice, this same assessment would be undertaken for each investment activity (Step 2C). The aggregate issue-specific data requirements and comments will then specify the full set of expectations regarding relevant data for climate change.

Step 3: Specify data quality expectations

These are defined by the expectations set out for general data needs on data quality.

Step 4: Specify data availability expectations

These are defined by the expectations set out for general data needs on availability.

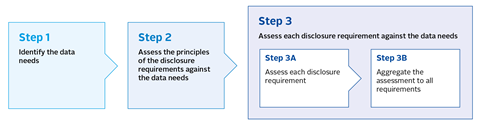

Application to standards, rules and laws

This involves three steps, as set out in Figure 7, beginning with identifying the data needs that are applicable to the standard, rule or law (Step 1) before assessing the principles of the disclosure requirements against the data needs (Step 2) and for each disclosure requirement (Step 3).

Figure 7: Steps to apply data needs to standards, rules and laws

Step 1 is defined by the results of the previous use case (to identify data needs) for the corresponding disclosure standard, rule or law.

Steps 2-3 assess the disclosure standard, rule or law using the data needs defined in Step 1 against the standard at two different scales. This is best illustrated through case studies to apply the data needs identified in the previous section:

- Assessment of Exposure Draft on IFRS S1: This tests the framework’s general data needs against a general standard – namely the ISSB general standards exposure draft;

Case study: Assessment of Exposure Draft on IFRS S1

This case study examines a partial assessment of the Exposure Draft on IFRS S1 General requirements for Disclosure of Sustainability-related Financial Information[50] against the general data needs.

Step 1: Identify the data needs

The general data needs have been specified in the case study on general data needs.

Step 2: Assess the principles of the disclosure requirements against the data needs

Assessment of the Exposure Draft’s principles (Table 6) indicates strong alignment with investors’ data needs, with the only gaps identified around the accessibility of the data (likely to be addressed through the forthcoming IFRS Digital Taxonomy) and the availability of contextual information on a company’s location, product lines, etc.

Table 6: Assessment of the principles of IFRS S1 ED

| Expectations for the principles of the disclosure requirements | Assessment of the principles | |

|---|---|---|

|

Requirement I: Data must be available |

|

The draft standard facilitates accessibility, particularly as it requires disclosure in management reports. However, it is not possible to comment on the format nor whether the disclosure is machine readable until the Digital Taxonomy is formalised. |

|

Requirement II: Data must be of sufficient quality |

|

All three characteristics are part of the qualitative characteristics of information that underpin the draft standard. The definitions are also in line with the PRI’s understanding of these terms. |

|

Requirement III: Data must be relevant |

|

The draft standard meets most of the requirements listed. The only requirement it does not meet is that the exposure draft standard does not explicitly include contextual information. This may be captured in other parts of the management reporting. |

Step 3: Assess the data needs for each disclosure requirement

The assessment of the disclosure requirement for Governance (Paragraph 26) is set out in Table 7 (Step 3A). The results indicate that, although the disclosure requirements were decision-useful, there were minor gaps identified on fair representation, comparability and the qualitative information needed to explain changes to investors’ processes.

Table 7: Assessment of strategy disclosure requirements in IFRS S1 ED

| Expectations for a specific disclosure requirement within the standard | Assessment at disclosure level | |

|---|---|---|

|

Risk management disclosure requirements (Paragraph 26) To achieve this objective, an entity shall disclose: (a) the process, or processes, it uses to identify sustainability-related: (i) risks; and (ii) opportunities; (b) the process, or processes, it uses to identify sustainability-related risks for risk management purposes, including when applicable: (i) how it assesses the likelihood and effects associated with such risks (such as the qualitative factors, quantitative thresholds and other criteria used); (ii) how it prioritises sustainability-related risks relative to other types of risks, including its use of risk-assessment tools; (iii) the input parameters it uses (for example, data sources, the scope of operations covered and the detail used in assumptions); and (iv) whether it has changed the processes used compared to the prior reporting period; (c) the process, or processes, it uses to identify, assess and prioritise sustainability-related opportunities; (d) the process, or processes, it uses to monitor and manage the sustainability-related: (i) risks, including related policies; and (ii) opportunities, including related policies; (e) the extent to which and how the sustainability-related risk identification, assessment and management process, or processes, are integrated into the entity’s overall risk management process; and (f) the extent to which and how the sustainability-related opportunity identification, assessment and management process, or processes, are integrated into the entity’s overall management process. |

||

|

Requirement I: Data must be available |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Requirement II: Data must be of sufficient quality |

|

Disclosure requirements are largely a fair representation. However, we identified a divergence in disclosure requirements for risks compared with opportunities, which could compromise the need to be unbiased. Of particular note is a gap in disclosure requirements equivalent to paragraph 26(b)(i)-(iv). |

|

Disclosure requirements are largely comparable. However, there are concerns regarding the lack of guidance on identification, assessment and prioritisation for risk management purposes (Paragraph 26(b)) and processes to monitor and manage risks and opportunities (Paragraph 26(d)). This lack of guidance could result in differences in disclosure by companies. |

||

|

No points identified on verifiability. |

||

|

Requirement III: Data must be relevant |

|

The only gap identified was on the requirement to disclose whether the company has changed its processes (Paragraph 26(b-iv)). Feedback from signatories indicates that investors would expect to see more information on why this has changed and the implications of the change. |

As illustrated by the assessment for Paragraph 26(b-iv), the framework provides a clear structure and evidence-based approach to assess disclosure standards, rules and laws. However, it still requires engagement with investors to identify requirements not captured by the framework, given the scale at which data is defined in the Framework.

In practice, this same assessment should be undertaken for all 92 paragraphs of the Exposure Draft (Step 2C). The aggregate assessments and comments will then complement the principle-based assessment to specify the technical review of the Exposure Draft on IFRS S1 General requirements for Disclosure of Sustainability-related Financial Information.

- Assessment of TCFD disclosure for forecasted data needs: This tests the data needs identified in the previous section on climate change against the TCFD’s disclosure requirements.

Case study: Assessment of TCFD disclosure for forecasted data needs

The case study covers a partial assessment of the recommendations of the TCFD[51] against the climate data needs for forecasted financials.

Step 1: Identify the data needs

The partial climate change data needs have been specified in the case study on climate change data needs for forecasted financials.

Step 2: Assess the principles of the disclosure requirements against the data needs

A full assessment of Step 2 is not possible for the TCFD recommendations as it does not have all of the principles of a formalised standard, rule or law.

This is particularly the case for availability (e.g., it does not have elements like a digital taxonomy) and quality (e.g., there are no definitions of the characteristics of information and no third-party verification is required on reporting).

For relevance, a partial assessment is possible, as set out in Table 8. The results show that, although the disclosure requirement meets a number of expectations, it does not provide a breadth of data types (particularly contextual information) and it does not require a clear definition of the operational boundary. Note the former point may be by design, as the TCFD recommendations are not intended to be a standalone disclosure document and will be used alongside other reporting.

Table 8: Assessment of the principles of TCFD – on relevance

| Expectations for the principles of the disclosure requirements | Assessment of the principles |

|---|---|

|

The disclosure requirements do not include contextual information or operational performance data. |

|

Disclosure is at the business entity level. |

|

Requirements include data across different time horizons. |

|

Requirements include a combination of quantitative and qualitative data. |

|

This is not a formal requirement of the disclosure requirements. |

Step 3: Assess each disclosure requirement against the data needs

The partial assessment of the disclosure requirements on the four pillars of the TCFD against the data needs defined for forecasted financials is set out in Table 9 (Step 3A and 3B). It maps the metrics in the TCFD disclosure against the data characteristics of the framework, before using the issue-specific requirements identified in Table 5 to identify gaps in the disclosure (see the final column).

Even though it is a partial assessment, it provides useful insights. It identifies that most of the quantitative indicators in the climate-specific data needs are already included within the TCFD recommendations.

However, the assessment finds the following gaps:

- There are gaps in contextual data and operational performance[52] to inform investors’ forecasting, as noted in Step 2;

- Disclosure is partially decision-useful on alignment of the company’s strategy with its commitments. Although there are no formal disclosure requirements to address this need in the recommendations, the TCFD’s 2021 guidance on metrics, targets and transition plans[53] expands on the recommendations to specify the need for “actions and activities to support transition, including GHG emissions reduction targets and planned changes to businesses and strategy”; and

- There is no third-party verification of the data used to inform the forecasting.

Table 9: Assessment of TCFD metrics – Issue-specific data needs – forecasted financials on climate change

| Data characteristics | Issue-specific requirements | TCFD | Assessment of gaps in disclosure | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Governance | Strategy | Risk management | Measures of financial performance* | Scope 1 & 2 | Scope 3 | Emissions intensity | Scenario analysis | ||||

|

Type of data |

Contextual data |

||||||||||

|

Material ESG issues |

|||||||||||

|

Processes |

|||||||||||

|

Operational performance |

|||||||||||

|

Financial performance |

|||||||||||

|

Sustainability performance |

|||||||||||

|

Sustainability outcomes |

|||||||||||

|

Nature of data |

Quantitative indicator – absolute/relative value |

||||||||||

|

Quantitative indicator – score/rating |

|||||||||||

|

Qualitative – pre-defined |

|||||||||||

|

Qualitative – open (inc. case studies) |

|||||||||||

|

Time horizon |

Historic – trends |

||||||||||

|

Current – point in time |

|||||||||||

|

Forward-looking – point in time/change |

|||||||||||

|

Granularity |

Portfolio level |

||||||||||

|

Sector/geographic level |

|||||||||||

|

Business entity level |

|||||||||||

|

Asset or economic activity level |

|||||||||||

|

Value chain data |

|||||||||||

|

Verification of underlying data |

|||||||||||

| Requirements for specific data characteristics (see Table 5) | |

| Data requirement met by disclosure that follows TCFD recommendations | |

| Relevant disclosure | |

| Disclosure is partially relevant | |

| Gaps in disclosure |

*TCFD metrics on financial performance include: (i) the amount and extent of assets or business activities vulnerable to transition risks; (ii) the amount or extent of assets or business activities vulnerable to physical risks; (iii) the proportion of revenue, assets or other business activities aligned with climate-related opportunities; (iv) the amount of capital expenditure, financing or investment deployed toward climate-related risks and opportunities; (v) the proportion of executive management remuneration linked to climate considerations; and (vi) the potential impact of climate-related issues on financial performance and financial position.

For the PRI, this process is a key part of developing its evidence base to inform its engagement with standard setters and regulators, which will be complemented by engagement with its signatories.

Next steps

For the PRI, the next steps for the Investor Data Needs Framework are three-fold.

1. Engage on the framework

Following the launch of this report, the PRI will seek feedback on the framework from signatories, policy makers, standard setters and other stakeholders on how the framework, particularly the relevance matrix in Appendix 3, can be applied. This period will include at least one workshop or roundtable with PRI signatories to gather feedback and discuss future updates to the framework.

2. Apply the framework to PRI’s engagement with standard setters and regulators

The framework will help the PRI understand the breadth of its signatories’ needs regarding corporate sustainability data, to further evidence the PRI’s engagement with standard setters and regulators in 2023 and beyond. In particular, it will be applied to issue-specific disclosure standards, rules and laws through the following steps:

- identifying data needs for priority issues – expanding the applications on human rights and climate change data needs to PRI’s priority issues, to identify the full set of data needs for each issue; and

- developing the PRI’s position on forthcoming issue-specific disclosure standards, rules and laws – building on the previous task to assess the issue-specific standards such as the Taskforce on Nature-Related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) and the ISSB’s forthcoming issue-specific standards (beyond climate). This would apply an expanded approach to the example in the final case study on the TCFD recommendations.

3. Update the framework

The framework will be updated in 2024 with a new report using the insights from:

- Feedback from PRI signatories and other stakeholders;

- Lessons learnt from applying the framework to issue-specific standards, rules and laws;

- A scoping assessment of potential high-priority areas to further expand the framework, such as other sources of data (e.g., data on companies reported by governments) and asset classes (e.g., alternatives); and

- Updates to the general data needs, based on updates to the PRI’s guidance on responsible investment practice.

This updated framework will help the PRI to provide clarity on the diversity in data needs across responsible investors. In particular, the current iteration of the framework is agnostic regarding the importance of elements of the framework to responsible investors, including which strategies and activities are most prevalent. As a result, this paper does not provide an indication of what investor data needs are most important when designing corporate sustainability disclosure standards for responsible investors as a group of users.

The framework does not go as far as to specify such a hierarchy, as current insights would only provide a snapshot of current and prevailing practice within the responsible investment community. This gap will be addressed in the updated framework, by combining the feedback from PRI signatories with the lessons learnt from applying the framework to different sustainability issues.

This will help standard setters and regulators develop a sense of what data is most important for responsible investors today and in the future. Similarly, for the PRI, it will inform our understanding of investor data needs, reflecting both the current state of responsible investment practice, including the role of regulatory requirements for investors, and the direction of travel of responsible investment practice for the PRI and its signatories.

For further information about the framework and these next steps, please reach out to [email protected].

Appendix 1: High-level review of data quality characteristics

The table below provides a high-level mapping of the terms used in the Investor Data Needs Framework against key standards and papers on data needs.

| Investor Data Needs Framework | Requirement I: Data must be available | Requirement II: Data must be of sufficient quality | Requirement III: Data must be relevant | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Characteristic | Produced | Accessible | Fair representation | Comparable | Verifiable | Relevant |

|

Relevance |

|||||||

|

Fair representation |

|||||||

|

Comparability |

|||||||

|

Verifiability |

|||||||

|

Timeliness |

|||||||

|

Understandability |

|||||||

|

Relevance |

|||||||

|

Faithful representation |

|||||||

|

Comparability |

|||||||

|

Verifiability |

|||||||

|

Understandability |

|||||||

|

Accuracy |

|||||||

|

Balance |

|||||||

|

Clarity |

|||||||

|

Comparability |

|||||||

|

Completeness |

|||||||

|

Sustainability context |

|||||||

|

Timeliness |

|||||||

|