This report summarises the outcomes of the PRI Investor Working Group on Sustainable Palm Oil. As of 2021, the group comprised of 64 investors with USD$7.9 trillion in assets under management. The working group’s aim was to tackle deforestation by coordinating engagement with companies across the palm oil supply chain.

This document tracks the results of engagement specifically with 24 companies that grow, process and trade palm oil, and 10 banks in Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore.

We gathered data from the Zoological Society of London’s (ZSL) SPOTT benchmark and WWF’s Sustainable Banking Assessment tool to track company progress on their deforestation-related policies and practices. Along with the results, we recommend how to continue stewardship activities in this area.

The working group was set up in 2011; however, this document pertains to the results of engagement with companies in the two abovementioned sectors between 2017 and 2021.

The interim evaluation documented progress between 2011 and 2016, focusing on major buyers and retailers of palm oil-based products. It found that company scores had improved overall. The greatest areas of improvement were:

- disclosure (e.g., reporting the size of landbanks, planted areas, smallholders and high conservation value areas); and

- policy and strategy (e.g., no deforestation on high-carbon stock and high conservation value areas and development on peat lands, and forbidding human rights violations, and extending these policies throughout the supply chain).

The area with least improvement was performance (i.e., the outcomes of the policies and their implementation).

Why tackle commodity-driven deforestation?

Forests are essential to the planet’s ability to regulate climate and water cycles, host biodiversity, prevent soil erosion, and directly sustain the lives of 1.3 billion people. Deforestation is often linked to human rights abuses such as land grabbing and modern slavery. It also threatens our ability to rely on the planet’s ecosystem services, for example climate regulation and biodiversity.

Agricultural expansion accounts for 80% of deforestation worldwide. The World Resources Institute’s Global Forest Review identified cattle, palm oil and soy as the commodities most likely to replace forested land between 2001 and 2015. Cattle pasture now occupies 45.1 million hectares (Mha) of land deforested between 2001 and 2015, accounting for 36% of all tree cover loss associated with agriculture during the timeframe examined. Oil palm (the area that the oil palm trees occupy) ranks second (10.5 Mha), followed by soy (8.2 Mha).

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nation’s State of the World’s Forests 2020 report highlights that deforestation is continuing at alarming rates, although with marked regional differences. Continued investor action is crucial to ensure commodity production is decoupled from environmental degradation and human rights abuses.

Why focus on palm oil?

Palm oil is the most widely used vegetable oil and boasts several advantages compared to its substitutes, including versatility, low cost and high yield. It has contributed significantly to economic development in a number of countries, in particular Indonesia and Malaysia, which together produce over 85% of the world’s crude palm oil.1

However, the development of palm oil plantations has also been linked to significant negative social and environmental impacts, including widespread deforestation, increased greenhouse gas emissions, social conflicts and damage to ecosystem services.2 All of these impacts pose material risks to investors.

Engagement Objectives and Company asks

As of March 2021, over 60 investors engaged with 34 companies, including palm oil growers, buyers, and banks.

High-level objectives

The PRI Investor Working Group’s high-level objectives were to:

- raise awareness amongst investors of the ESG issues that arise within the palm oil value chain, including deforestation, land and labour rights issues, and climate risks;

- provide a unified investor voice in support of sustainable palm oil; and

- engage with companies across the value chain to promote a sustainable industry, including by improving companies’ disclosure and management of ESG risks.

Company asks

The working group expected companies to become members of the not-for-profit Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) – the most well-recognised sustainability certification for palm oil – and apply its principles and criteria. Where this was not possible, as a minimum first step, investors expected companies to publish and implement a public No Deforestation, No Peat and No Exploitation (NDPE) policy.

In addition, companies were asked to:

- commit to full traceability, down to plantation level;

- promote yield improvements rather than expand production into new land; and

- report regularly on progress and practices.

Timeline of activities

Over time, the investor working group has engaged with several segments of the palm oil supply chain. The rationale for our work is explained below.

2011: The PRI Investor Working Group on Sustainable Palm Oil is formed

The working group focused first on the major buyers and retailers of palm oil-based products. Companies were asked to become RSPO members. Companies that were already RSPO members were asked to disclose a timeframe for purchasing certified sustainable palm oil (CSPO). Progress was slowed by the lack of CSPO on the market, which prevented companies from committing to sourcing CSPO.

2014: Working group engages palm oil growers, processors and traders

In 2014 the group began to engage the key palm oil growers, processors and traders. A list of 24 priority companies was drawn up, primarily in Indonesia and Malaysia. Engagement continued with these companies from 2014 until the collaborative engagement ended in 2021.

2019: Working group engages with banks

Investors started to engage with 10 ASEAN (Indonesian, Malaysian and Singaporean) banks that provide financial products and services to clients within the palm oil industry. These banks have greater exposure to a wider range of companies within the palm oil sector than investors. The aim was therefore to encourage them to better monitor the environmental and social risks of financing the palm oil industry, including engaging their clients to help them improve their practices.

Separately that year, more than 60 investors and working group members with approximately USD$7.9 trillion in assets under management laid out their expectations of companies on sustainable palm oil in a signed letter.

2020: Working group addresses FMCG companies in ‘leakage markets’

In early 2020, the investor group highlighted the need to engage with companies in some of the largest palm oil-consuming markets. A total of 10 Asian nations were identified as ‘leakage’ markets where palm oil could be traded at the lowest price without being held to account on sustainability, and therefore they were priority markets in which to increase CSPO demand.

The PRI coordinated a pilot engagement with seven major FMCG companies in Asia from early 2020 until the wider collaborative engagement ended in 2021. Given the impact of Covid-19 and the resulting short timeframe, we do not present the results in this document and this pilot will inform future engagement.

Below we outline the results of engagement with the growers, processors, traders and ASEAN banks from 2017 to 2021.

Growers, processors and traders

Out of all the engaged sectors, growers, processors and traders were engaged for the longest period of time. The working group wanted to:

- improve transparency of land ownership, concession areas and level of RSPO certification;

- improve transparency of CSPO in a way that supports segregated supply chains;

- request clear commitments to policies beyond RSPO that prohibit deforestation, peatland development and human rights violations; and,

- encourage growers to focus more on yield gains over further land use.

Engagement focused on monitoring company progress towards implementing NDPE commitments or achieving 100% CSPO. Additionally, investors engaged with companies as controversies arose, many of which were related to labour rights infringements.

A total of 24 Indonesian and Malaysian major growers, processors and traders of palm oil that featured on the ZSL SPOTT ranking were selected for engagement. Letters were sent to all 24 companies on the engagement list, and follow-up engagement took place with 13 companies.

Methodology

We used data from the ZSL SPOTT ranking to inform company engagement with growers, processors and traders.

ZSL SPOTT is a free, online platform that assesses commodity producers, processors and traders’ transparency on environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues. Every year palm oil, tropical forestry and natural rubber companies are marked against more than 100 sector-specific ESG indicators. The companies receive an overall score for each commodity, allowing investors to view progress over time. By tracking transparency, SPOTT incentivises corporate best practice.

How we used ZSL SPOTT’s overall company scores to compare progress

To assess company progress, we initially looked at the overall ZSL SPOTT score (which assesses companies on 182 indicators). We compared overall scores of companies that had been sent letters (engaged) and those companies that were not sent letters (non-engaged) over the same period.

How we picked relevant indicators to score companies against

As mentioned, the overall company score looks at 182 indicators. The ZSL SPOTT team looked at what investors expected of companies and matched those asks with the most relevant indicators. Out of this offering, we narrowed it down further, according to relevance and prioritising those indicators that offered consistent comparison since the start of the engagement in 2017.

A table showing how 2021 indicators were aligned with investor expectations is included in Appendix A. From this most recent alignment exercise, out of a total of 22 indicators, 11 of the were considered most relevant and selected for analysis and commentary in this document.

This document attempts to compare engaged and non-engaged companies for some indicators, and we also compare overall scores in the charts below. This comparison should be caveated: the 24 engaged companies made up less than a quarter of the total number of companies on the ZSL SPOTT benchmark, and as listed companies were likelier to be larger and therefore more inclined to address reputational and other risks related to deforestation. These larger companies were also more likely to be held by institutional investor participants and hence more likely to respond to engagement.

Results

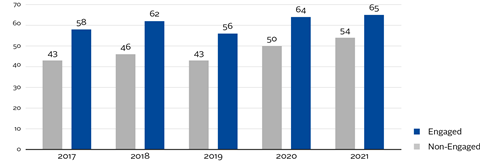

Overall scores of engaged companies increase by seven points

ZSL SPOTT scores can act as a proxy for palm oil growers’, processors’ and traders’ overall ESG performance over time.

Figure 1: Average overall ZSL SPOTT scores

Average overall scores increased by seven percentage points between 2017 and 2021 for companies engaged by working group members, compared to an average increase of 11 points in scores for non-engaged companies.

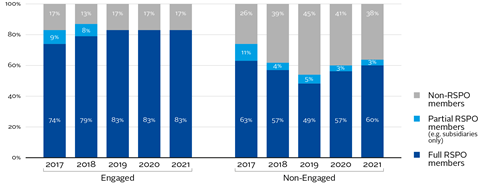

RSPO membership increases by 9 percentage points amongst engaged companies

RSPO member companies are regularly audited, therefore RSPO membership is a useful indicator of a company’s commitment to making palm oil supply chains more sustainable.

Figure 2: RSPO membership

Of the 24 engaged companies covered by ZSL SPOTT, 17 companies were full RSPO members in 2017, increasing to 19 in 2021.

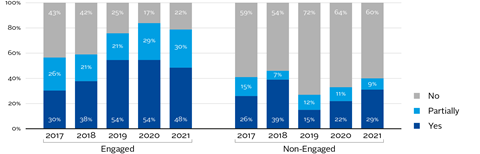

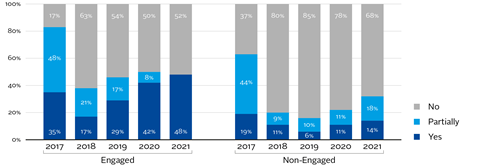

Engaged companies see an increase of 18 percentage points in time-bound commitments to achieve traceability to the plantation level

Without traceability to the earliest point of production of palm oil - the plantation - it is hard to know whether the commodity is linked to deforestation or not. Traceability commitments are therefore important in increasing supply chain transparency and form a good basis for sustainability action.

Figure 3: Time-bound commitment to achieve 100% traceability to plantation level

The number of engaged companies that committed to achieving 100% traceability to the plantation level increased from seven to 11 companies between 2017 and 2021. In 2021, there were five engaged companies that still did not commit to this level of traceability. In 2021, one engaged company’s score deteriorated as it failed to achieve its 2020 commitment. ZSL SPOTT awards partial points for the indicator if the target has passed and has not been met, among other reasons.

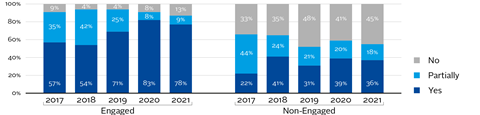

Company concessions maps made public by 77% of engaged companies, compared to 52% at the start of the engagement

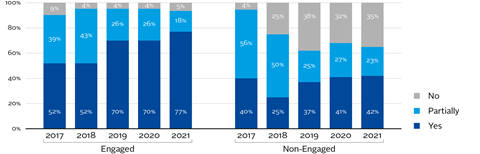

A company’s public concession map3 helps investors and other stakeholders to track, monitor and verify any land conversion activities and link them to relevant companies.

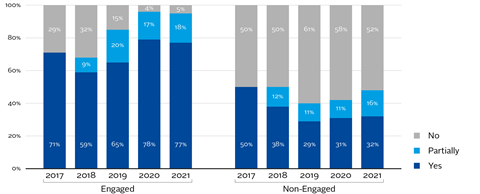

Figure 4: Public availability of company’s concession maps

As of 2021, concession maps were fully available for 17 companies, compared to 12 in 2017. Only one company had no publicly available maps at all, while four companies scored partial points, as it could not be confirmed that all their operations were covered, and / or only partial information was provided (e.g., concession boundaries were not shown).

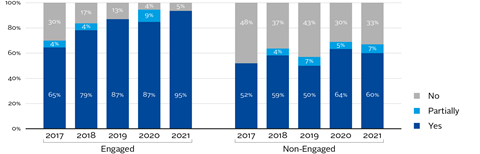

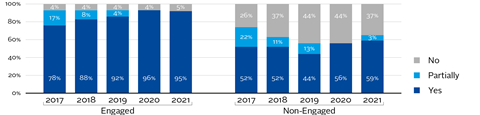

95% of engaged companies now have ‘no deforestation’ commitments

Company commitments do not always precede action; however, they can be a good starting point for monitoring performance and progress.

Figure 5: No deforestation commitments

Companies with deforestation commitments increased from 15 in 2017 to 21 in 2021. Only one company had no public commitment in 2021, compared to seven in 2017. Many of those that made commitments have done so either through RSPO or NDPE, while others have standalone deforestation policies that include pledges to not convert areas of high conservation value and high carbon stock.

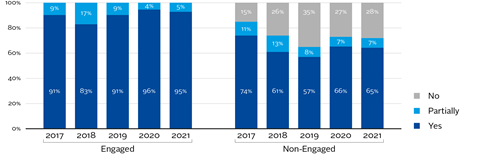

Engaged companies committed to zero burning increased by 4 percentage points

Burning is commonly used to clear land for plantations. When carried out indiscriminately, this practice destroys forest ecosystems and causes health issues for communities across Southeast Asia due to the smoke or ‘haze’. Burning peat is particularly dangerous due to the difficulty in extinguishing fires, as well as the heightened density and high sulphur content of the resulting haze. Companies should commit to monitoring and addressing fires connected to their business operations and supply chain.

Figure 6: Commitments to zero burning

As of 2017, all engaged companies had some form of public zero burning commitment, and this remained the case in 2021.

Engaged companies with partial scores decreased from 9% to 5% in 2021. Partial scores were awarded to companies where the commitment does not cover all operations (e.g., only one country), or if the company only has a commitment to limiting the use of fire.

95% of engaged companies now commit to not plant on peat of any depth

Planting on peat poses further challenges. The drainage required for palm oil cultivation causes peat oxidation and makes the soil susceptible to fires and floods, as well as biodiversity loss and high C02 emissions.

Figure 7: Commitment to not plant on peat of any depth

Engaged companies with commitments to not plant on peat of any depth increased from 14 in 2017 to 21 in 2021. As of 2021, there was one engaged company without a commitment.4

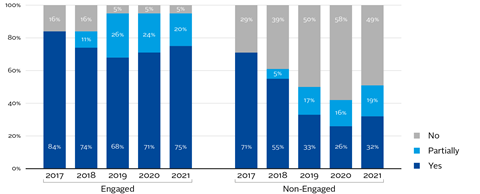

48% of companies have a time-bound commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emission intensity, compared to 35% at the start of the engagement

Palm oil growers, processors and traders contribute to greenhouse gas emissions through land cover change (i.e., the loss of natural forest areas), peat drainage, emissions from mills, transport and other operations. It is therefore important for companies to have time-bound specific commitments to reduce their emission intensity.

Figure 8: Time-bound commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions intensity

Improvements seem to be taking place slowly. In 2021, 11 companies had commitments in this area, compared to eight in 2017. However, 12 companies remained without commitments in 2021. It should be noted that ZSL SPOTT’s scoring in this area became stricter, so in 2021 many companies were awarded no points for having a commitment that was not timebound or intensity-based, whereas they would have scored partial points in previous years.

78% of engaged companies are committed to International Labour Organisation (ILO) standards or Free and Fair Labour Principles, compared to 57% at the beginning of the engagement

Palm oil is one of the most labour-intensive vegetable oils. Workers risk coming into contact with harmful pesticides and fertilisers while undertaking maintenance tasks. Additionally, cases of labour rights violations such as retaining passports and indebting migrant workers have been well-documented. It is therefore important that companies commit to the ILO’s fundamental conventions, or the Free and Fair Labour Principles for Palm Oil, which set out a common point of reference on what constitutes free and fair labour in palm oil production.

Figure 9: Commitment to the fundamental ILO conventions or Free and Fair Labour Principles

Engaged companies that fully met requirements increased from 13 in 2017 to 18 in 2021. As of 2021, two companies were awarded partial scores as, despite their commitment to some of the fundamental ILO conventions (e.g., freedom of association, no child labour, no discrimination)5, they did not publicly commit to equal remuneration. In the same year, another three companies scored zero. Two of them committed to respecting worker rights but there was no mention of compliance with the aforementioned standards.

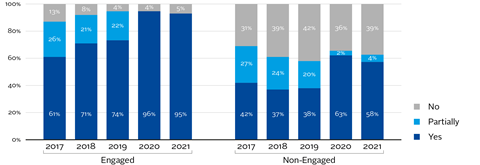

Engaged company commitments to free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) have increased by 17 percentage points

Free, prior and informed consent is a collective human right of indigenous peoples and local communities to give or withhold their consent prior to any activity commencing that may affect their rights, land, resources, territories, livelihoods and food security. FPIC should be respected even in cases where there is no guarantee that such communities are protected under national laws.

A number of human rights violations by palm oil companies have been documented over the years in relation to seizing community lands without consent, involuntary displacement and even violence against displaced indigenous peoples and communities. It is therefore important for companies to commit to and comply with FPIC.

Figure 10: Commitment to free, prior and informed consent

In 2017, most engaged companies (18) already had an FPIC commitment, rising to 21 in 2021. Many of these companies, by virtue of complying with RSPO principles and criteria, would have an FPIC commitment in place. One company still did not have such a commitment in 2021.

77% of engaged companies support independent smallholders, and 75% support scheme smallholders

Smallholders — defined by the RSPO as managing plantations of 50 hectares (ha) or less — account for about 40% of global palm oil production. Smallholders can be categorised as either ‘associated’ / ‘scheme’ (or ‘plasma’, or, named after an Indonesian government scheme where companies are required to provide a section of land for smallholder farmers), or as independent smallholders that finance, equip and manage themselves, and are not bound to any one mill.

Oil palm can offer attractive returns for smallholders. Yet when comparing smallholders with palm oil companies, the latter has an overall advantage in terms of contracts, efficiencies, and yields. Without adequate support programmes, smallholders may face risks such as price volatility, lower yields and crop disease, which can impact companies’ supply.

Figure 11: Programme to support scheme/plasma smallholder

Figure 12: Programme to support independent smallholders

Engaged companies had similar levels of support for plasma and independent smallholders. As of 2021, only one company reported that it did not provide support for either. Partial scores were awarded to four companies in both categories, mainly because their claims to support smallholders were not externally verified. Higher scores in 2017 can be linked back to lesser stringency in scoring (e.g., no need for external verification).

ASEAN banks

After much public pressure, larger companies in the palm oil industry now tend to have an NDPE commitment. However, many smaller companies do not. This less liquid portion of the market is commonly financed through banks, rather than institutional investors.

The working group therefore engaged with 10 banks across Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore. The working group hoped that, through the banks’ financing and lending activities, the banks could influence companies to adopt more sustainable practices.

The first key step for banks was to have a public policy regarding their lending to and financing of the palm oil sector. Investors suggested that banks could also request their clients commit to NDPE or become RSPO members.

Methodology

WWF’s Sustainable Banking Assessment tool The investor working group used data from WWF to see where companies were making or lacking progress, which would inform engagement with those companies. WWF’s Sustainable Banking Assessment (SUSBA) tool shows year-on-year changes of banks’ performance in terms of integrating environmental and social considerations into their corporate strategy and decision-making processes. The SUSBA tool also assesses banks’ policies for specific sectors and issues, including palm oil sustainability.

Below we look at banks’ progress on a selection of palm oil indicators from the SUSBA tool. All palm oil indicators are available on the WWF SUSBA website and are listed in Appendix B of this document.

In conducting this analysis, it should be noted we were limited by the lack of data in 2019. We are therefore only able to compare 2020 and 2021 data. As such, it would be difficult to assess progress. This report rather aims to provide a snapshot of the state of bank policies on palm oil as a basis for further engagement.

Results

Does the bank identify palm oil as a key sector and have a specific policy / approach (for palm oil or agriculture)? (Indicator 1.1.1)

| 2020 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|

|

No |

1 |

1 |

|

Yes |

9 |

9 |

Does the palm oil sector policy apply to all banking operations and financial products? (Indicator 1.1.4)

| 2020 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|

|

No |

6 |

6 |

|

Partially |

1 |

1 |

|

Yes |

3 |

3 |

Does the bank disclose the full sector policy document? (Indicator 1.2.1)

| 2020 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|

|

No |

9 |

9 |

|

Yes |

1 |

1 |

Does the bank require clients to adopt ‘no deforestation’ commitments? (Indicator 2.5.2)

| 2020 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|

|

No |

7 |

7 |

|

Partially |

1 |

|

|

Yes |

3 |

2 |

Nine banks identified palm oil as a key sector and have a specific policy or approach for palm oil and / or agriculture. However, only three banks’ policies applied to all operations and financial products. One bank scored partial points due to its exclusion of SMEs.

Only one out of the 10 banks publicly disclosed its full sector policy document. Engaged banks expressed reluctance to go beyond their respective legal requirements. WWF analysis notes that policies tended to focus on upstream producers, whereas suppliers, third parties and downstream manufacturers and retailers were not generally covered.6

Of the banks engaged, Singaporean banks appear to perform better than those in Indonesia and Malaysia. Indonesian banks did show some progress in terms of their general approach to sustainable finance, possibly due to sustainable finance regulation implemented in 2019 by the Indonesian financial regulator.

Client requirements were only implemented by two banks out of 10. Many of the engaged banks expressed concern around tightening lending criteria as they would risk losing clients. Increasing sustainability requirements seemed particularly challenging in the case of existing clients that require engagement. However, lending and financing criteria tended to already be higher for new clients, including requiring Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil or Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil certification, therefore banks found it easier to encourage new clients to acquire RSPO certification too.

FMCG companies

Asian FMCG companies were selected for engagement due to the sector’s role as a growing leakage market for unsustainable palm oil. Investor engagement was therefore seen as an important lever to help boost demand for sustainable palm oil. It was decided to pilot the impact of such an engagement through initial dialogue with a small number of companies.

Using WWF Singapore research, the working group drafted a list of 31 companies recommended for engagement, from which seven companies were selected for the pilot.

The key engagement ask was for companies to commit to making a public policy regarding their sourcing of palm oil and a time-bound commitment to source 100% sustainable palm oil.

Engagement began with sending letters to the seven selected companies in early 2020; however, the project was severely impacted by the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic. Results were mixed, with some companies agreeing to review the asks and aim to implement a policy, while others were reluctant to hold dialogues with investors.

We recommend further collaborative engagement, given the importance of the Asian FMCG sector in driving palm oil demand.

Overall, the engagement saw companies increasingly commit to addressing deforestation within their operations and supply chains. These improvements reflect that of the palm oil industry more broadly, with over 80% of palm oil refining capacity covered by an NDPE commitment as of 2020.7

Looking at real-world outcomes, it is encouraging to see that both Indonesia’s and Malaysia’s primary forest8 loss rates have been decreasing since 2017.9 High palm oil prices tend to drive increases in deforestation, due to plantations expanding into previously forested areas to produce more oil palm and increase revenues. This connection between increasing prices and increased deforestation seems to have been stopped, at least momentarily.10

While company commitments appear to have helped to slow deforestation rates,11 government action has been crucial too. After devastating peat fires in 2015, Indonesia issued a temporary moratorium on new oil palm plantation licences and a permanent moratorium on primary forest conversion, and Malaysia established a five-year cap on plantation area expansion in 2019 and planned to toughen legal action against loggers.12

Despite this progress, much remains to be done to ensure the palm oil industry fully adopts practices that do not harm people and the environment. Experts have warned that the end of the temporary moratorium on new plantation licences in Indonesia may encourage a return to deforestation.13 Leakage markets with lower sustainability requirements,14 and Indonesia’s 2020 biofuel mandate to use 30% palm-based fuel15 are also a concern.

Some key learnings from our engagement are below:

- Traceability is an important lever for sustainability in palm oil supply chains.

In recent years, larger, the promise of higher revenues has led vertically-integrated producers to focus more on refining, rather than growing, palm oil. These companies are turning to third-party providers to source palm oil fresh fruit bunches (i.e., the raw material for mills).16 Traceability to the plantation level and supplier engagement will be required to ensure companies are respecting NDPE and other no deforestation commitments. Examples of traceability systems include an investor partnership with Satelligence, which enables engagement with companies based on independent, satellite-detected deforestation data.

- Leakage markets for unsustainable palm oil are growing.

Global demand is growing for vegetable oils, due to their widespread use in the food industry and energy sector as feedstock for biofuels. This demand was further exacerbated by the search for substitutes to the now constrained supply of sunflower oil from Ukraine following the Russian invasion.17 There is a concern that this growing demand is in markets that are more price-sensitive and have fewer sustainability requirements, hence making sustainable and certified palm oil a less attractive and competitive option. It will be important to continue to monitor developments on the demand side, including domestic demand for palm oil as a biofuel feedstock in producing countries, and involve local stakeholders to ensure that growing demand for palm oil does not compromise its sustainability.

- Environmental sustainability can sometimes be perceived as a barrier to economic development, which is a priority for stakeholders in Southeast Asian countries.

At various points during engagement dialogues, discussions emerged around the perception that sustainable practices and economic development are not compatible. At the policy level, the EU Renewable Energy Directive II, which set a limit on biofuels linked to high-deforestation risk sources, was opposed by the Indonesian and Malaysian governments as well as by some producers’ associations, which claimed the policy amounted to protectionism and boycotting Southeast Asian biofuel feedstocks.18 At the company level, concerns were also raised around the inability to sell all certified palm oil at the premium it requires, due to a lack of demand. Banks were also generally reluctant to tighten lending sustainability requirements, due to concerns they would have to turn away clients who did not comply.

- Human rights violations frequently featured in engagement dialogue.

Palm oil is one of the most labour-intensive vegetable oil crops, requiring a large workforce for cultivation. Plantations, especially those located in Malaysia, have been experiencing labour shortages. This means that companies often heavily rely on recruiters and labour brokers to hire migrant workers on a contractual basis. Conditions on several plantations can be exploitative and abusive, as documented by NGOs.19 Additionally, NGOs have highlighted how oil palm plantations have adversely impacted the lives of indigenous populations and local communities.20 Investors in the sustainable palm oil working group have been increasingly engaging on the social issues side of palm oil sustainability in recent years, in response to the rising number of human rights controversies involving listed companies.

- The highest standards of certification are slow to take off.

Generally, the larger upstream companies engaged by investors qualified for RSPO certification. However, certified palm oil has struggled to move beyond the 20% mark of the global market.21 This is due to factors including lack of demand for certified palm oil and a lack of price premium associated with its production. Engagement dialogues also showed how RSPO is less popular in producing countries compared with NDPE commitments and local palm oil standards. While RSPO is still seen as the most stringent set of sustainability requirements,22 uptake of other schemes can be a first, positive step in the right direction.

Recommendations

We offer some recommendations for continued engagement on palm oil-linked deforestation below. These are not prescriptive, but rather suggestions for how investors can continue to build upon the sustainable palm oil working group’s efforts.

- Collaboration is necessary across all supply chain segments – and beyond.

While the environmental and social impacts of unsustainable palm oil production have gained a lot of traction in the EU and the US, the same sustainability concerns are not yet as widespread in Asian markets.23 Given this region is the biggest consumer of palm oil, future engagement should tackle potential leakage markets in this geography. Additionally, to prevent palm oil being substituted with equally or more unsustainable products, it will be important for engagement to continue with regards to other commodities, such as soy, which is linked to deforestation risk in Brazil. Given the global interconnectedness of palm oil and other vegetable oil supply chains and deforestation, it is crucial for all market actors to ensure palm oil is produced sustainably. Investors can support the global work of the RSPO and / or stakeholder initiatives focusing on sustainable palm oil in Asia, including the following:

- Singapore Alliance for Sustainable Palm Oil

- Sustainable Palm Oil Coalition for India

- Japan Sustainable Palm Oil Network

- China Sustainable Palm Oil Alliance

- Consult local stakeholders.

In the previous section, we mentioned the perceived tension between environmental and economic development needs. Future engagement should be framed as supportive of the palm oil industry’s transition to financial and well as environmental and social sustainability. Messaging and dialogues should not come across as antagonistic to the whole industry. Enhanced connections and collaboration with local stakeholders, whether they are local investors or members of civil society, may help in better framing dialogues so that they are as productive as possible. Additionally, engagement objectives should continue to address some of the barriers to the economic viability of sustainable palm oil, such as supporting business strategies that favour sustainable yield improvements over plantation expansion. Efforts to create demand for certified palm oil should also be supported, so that it can be sold at a premium that adequately compensates the cost of production.

- Address human rights as a key aspect of engagement on sustainable palm oil.

Deforestation often takes place alongside human rights violations. Labour and wider human rights controversies are a growing focus of investor engagement with palm oil companies. It will be important to ensure the social aspects of sustainable palm oil production and trading are addressed proactively during engagement and that companies have the right policies and processes to align with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. A recent Forest Peoples Programme report offers some insights on how due diligence and risk assessment processes might be improved through ‘ground-truthing’, gathering information from independent primary and secondary sources about what is happening on the ground, rather than relying on paper-based compliance.

- Focus on real-world sustainability outcomes, using all levers available, including policy engagement and escalation where necessary.

It will be crucial for any future engagement on deforestation to adopt an Active Ownership 2.0 approach, which prioritises sustainability outcomes. While it is encouraging to see reducing deforestation in Malaysia and Indonesia, global commodity-driven deforestation rates are on the rise, with many companies missing their commitments to halt deforestation in their operations and supply chains by 2020.24 It is crucial that collaborative engagement prioritises accountability and transparency, by using tools and approaches such as satellite monitoring, third-party verification and ground-truthing to ensure company policies and commitments result in a positive impact on the ground. Finally, where dialogue is not successful, escalation (e.g., voting against boards of laggard companies) should be implemented when necessary. Investors should also use a wide range of levers beyond traditional company dialogues, including policy engagement, to help address structural barriers to sustainable practices. The Investor Policy Dialogue on Deforestation (IPDD) is already actively coordinating policy engagement activities on deforestation in Indonesia, Brazil and other geographies.

Next steps

The PRI continues to address sustainable commodities and deforestation.

- Visit our Sustainable Land Use page for further resources, including information on PRI-coordinated collaborative engagements on deforestation and nature.

- To help inform engagement, investors can access a new ZSL SPOTT dashboard assessing individual companies against the ‘PRI expectations score’, which is based on the PRI’s sustainable palm oil investor expectation statement.

- Investors should also join other collaborative deforestation initiatives, such as the IPDD, hosted by the Tropical Forest Alliance (World Economic Forum). Those interested in engaging on human rights should apply to join Advance, a PRI-led collaborative stewardship initiative on social issues and human rights.

Appendix A: Selected ZSL SPOTT indicators

The below table shows how a selection of ZSL SPOTT’s 2021 indicators were aligned with our investor expectations. From this alignment exercise, 11 indicators considered most relevant were selected for analysis and commentary in this document. They are shaded blue below.

= Analysis highlighted in this report

| Investor Expectation Asks | ZSL SPOTT Indicators |

|---|---|

|

Members of the RSPO |

Member of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) |

|

Applies the RSPO’s Principles and Criteria

|

Percentage of area (ha) RSPO-certified |

|

Percentage of mills RSPO-certified |

|

|

Commit to full traceability to the plantation level |

Time-bound commitment to achieve 100% traceability to plantation level |

|

Regularly reports on progress and practices

|

Percentage of fresh fruit bunches (FFB) supply to own mills traceable to plantation level |

|

Percentage of supply from third-party mills traceable to plantation level |

|

|

Map and disclose their palm oil concession areas |

Maps of estates / management units |

|

No deforestation |

Commitment to zero deforestation |

|

No conversion of High Conservation Value (HCV) areas |

Commitment to conduct High Conservation Value (HCV) assessments |

|

No conversion of High Carbon Stock (HCS) forests |

Commitment to the High Carbon Stock (HCS) approach |

|

No burning in the preparation of new plantings and re-plantings |

Commitment to zero burning |

|

A progressive reduction in greenhouse gas emissions associated with existing plantations |

Time-bound commitment to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions intensity |

|

No development on peat regardless of depth |

Commitment to no planting on peat of any depth |

|

Implementation of RSPO Best Management Practices for existing plantations on peat |

Commitment to best management practices for soils and peat |

|

No Exploitation of People and Local Communities |

Commitment to respect indigenous and local communities’ rights; |

|

Respect and support the Universal Declaration of Human Rights |

Commitment to human rights |

|

Respect and uphold the rights of all workers including contract, temporary and migrant workers |

Commitment to Fundamental ILO Conventions or Free and Fair Labour Principles |

|

Facilitate the inclusion of smallholders into the supply chain |

Programme to support scheme / plasma smallholders |

|

Programme to support independent smallholders / outgrowers |

|

|

Respect land tenure rights |

Commitment to respect legal and customary land tenure rights |

|

Respect Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) of indigenous and local communities |

Commitment to free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) |

|

Resolve all complaints and conflicts through an open, transparent and consultative process |

Own grievance or complaints system open to all stakeholders |

Appendix B: SUSBA indicators

All indicators of the WWF SUSBA tool (38) are available on its website and are listed below. The four most relevant indicators, in terms of their aligning with engagement asks, are shaded blue and are selected for commentary and analysis in this paper.

= Analysis highlighted in this report

| 1) Purpose and scope | |

|---|---|

|

1.1.1 |

Does the bank identify palm oil as a key sector and have a specific policy/approach (for Palm oil or Agriculture)? |

|

1.1.2 |

Does the bank identify deforestation and / or conversion of natural ecosystems as a risk (environmental or business risk)? |

|

1.1.3 |

Does the bank provide incentives or offer financial products that support a transition towards sustainable practices in the sector? |

|

1.1.4 |

Does the palm oil sector policy apply to all banking operations and financial products? |

|

1.1.5 |

Does the bank acknowledge biodiversity loss and / or deforestation risks in its clients’ activities? |

|

2) Disclosure |

|

|

1.2.1 |

Does the bank disclose the full sector policy document? |

|

1.2.2 |

Does the bank disclose the environmental performance or impact of palm oil or agriculture portfolio (for example GHG emissions, land use change, biodiversity)? |

|

1.2.3 |

Does the bank disclose % or number of palm oil clients that are sustainably certified or have time-bound plan to achieve 100% sustainability certification? |

|

3) Reporting and monitoring |

|

|

1.3.1 |

Does the bank perform periodic review or state how frequent it reviews its clients’ profiles on E&S? |

|

1.3.2 |

Does the bank disclose the process to address non-compliance of existing clients with the bank’s policies or with pre-agreed E&S action plans? |

|

4) Upstream – own operations |

|

|

2.1.1 |

No Deforestation, No Peat, No Exploitation (NDPE) |

|

2.1.2 |

No clearance by burning |

|

2.1.3 |

Protect High Conservation Value (HCV) and High Carbon Storage (HCS) areas |

|

2.1.4 |

Protect key biodiversity areas, protected areas and species (IUCN Cat I-IV, WHS, Ramsar Wetlands, CITES, KBA) |

|

2.1.5 |

No planting on peat regardless of depth |

|

2.1.6 |

Respect the free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) of local and indigenous communities, as well as legal and customary user rights, for all new and existing plantations |

|

2.1.7 |

Require time-bound commitment to 100% RSPO certification |

|

2.1.8 |

Require reforestation plan or plan to restore degraded land, and improving habitats in existing plantations |

|

2.1.9 |

Require rehabilitation of peat upon the end of the planting cycle, and application of best management practices on peatland |

|

5) Upstream – suppliers / third parties |

|

|

2.2.1 |

No Deforestation, No Peat, No Exploitation (NDPE) |

|

2.2.2 |

No clearance by burning |

|

2.2.3 |

Protect High Conservation Value (HCV) and High Carbon Storage (HCS) areas |

|

2.2.4 |

Protect key biodiversity areas, protected areas and species (IUCN Cat I-IV, WHS, Ramsar Wetlands, CITES, KBA) |

|

2.2.5 |

No planting on peat regardless of depth |

|

2.2.6 |

Respect the free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) of local and indigenous communities, as well as legal and customary user rights, for all new and existing plantations |

|

2.2.7 |

Require time-bound commitment to 100% RSPO certification |

|

2.2.8 |

Require reforestation plan or plan to restore degraded land, and improving habitats in existing plantations |

|

2.2.9 |

Require rehabilitation of peat upon the end of the planting cycle, and application of best management practices on peatland |

|

2.2.10 |

Time-bound commitment to source 100% RSPO certified palm oil |

|

2.2.11 |

Commitment to achieve 100% supply chain traceability and ensure full legality of sourced fresh fruit bunches |

|

6) Downstream – refining and trading |

|

|

2.3.1 |

Time-bound commitment to source 100% RSPO certified palm oil |

|

2.3.2 |

Commitment to achieve 100% supply chain traceability and ensure full legality of sourced fresh fruit bunches |

|

2.3.3 |

Commitment to source No Deforestation, No Peat, No Exploitation (NDPE) |

|

7) Downstream – manufacture and retail |

|

|

2.4.1 |

Time-bound commitment to source 100% RSPO certified palm oil |

|

2.4.2 |

Commitment to achieve 100% supply chain traceability and ensure full legality of sourced fresh fruit bunches |

|

2.4.3 |

Commitment to source No Deforestation, No Peat, No Exploitation (NDPE) |

|

8) Crosscutting |

|

|

2.5.1 |

Support smallholder inclusion in the supply chain |

|

2.5.2 |

Require clients to adopt ‘no deforestation’ commitments |

Downloads

Investor working group on sustainable palm oil engagement results

PDF, Size 2.12 mb

References

1 IUCN (2018), Oil palm and biodiversity

2 IUCN (2018), Oil palm and biodiversity

3 Concession: the right to use land or other property for a specified purpose, granted by a government, company, or other controlling body (Lexico, accessed July 2022)

4 There are instances where an indicator may not apply to a particular sector a company belongs to (because of ZSL SPOTT’s methodology rather than our own)

5 ILO (2022), Conventions and Recommendations

6 WWF (2020), Sustainable Banking Assessment

7 Chain Reaction Research (2020), NDPE Policies Cover 83% of Palm Oil Refineries: Implementation at 78%

8 A forest that has never been logged and has developed following natural disturbances and under natural processes, regardless of its age (CBD, 2006)

9 WRI (2021), Forest Pulse: The Latest on the World’s Forests

10 Mongabay (2022), Have we reached peak palm oil? (commentary)

11 Chain Reaction Research (2020), NDPE Policies Cover 83% of Palm Oil Refineries: Implementation at 78%

12 WRI (2021), Primary Rainforest Destruction Increased 12% from 2019 to 2020

13 Mongabay (2021), ‘Forests will disappear again,’ activists warn as Indonesia ends plantation freeze

14 Chain Reaction Research (2021), Deforestation on Oil Palm Concessions Continued to Decline in First Half of 2021

15 BBC (2021), Indonesia’s biodiesel drive is leading to deforestation

16 zu Ermgassen et al (2022), Addressing indirect sourcing in zero deforestation commodity supply chains

17 Politico (2022), Ukraine war offers palm oil a comeback, to the horror of green groups

18 Unearthed (2019), How palm oil sparked a diplomatic row between Europe and southeast Asia

19 Amnesty International (2020), Why palm oil in products is bad news

20 Human Rights Watch (2019), “When We Lost the Forest, We Lost Everything”. Oil Palm Plantations and Rights Violations in Indonesia

22 Forest Peoples Programme (2017), A Comparison of Leading Palm Oil Certification Standards

23 Chain Reaction Research (2021), The Chain: Asian Markets’ Uptake of Certified Palm Oil Still Low Despite Positive Trends

24 Forest500 (2019), Implementing commitments beyond 2020