Stéphanie Giamporcaro, Nottingham Business School Nottingham Trent University and Graduate School of Business University of Cape Town; Jean-Pascal Gond, Bayes Business School, City, University of London; and Céline Louche, Waikato Management School, University of Waikato

Researchers have long stressed that further understanding our collective deliberative capacity when it comes to solving major challenges such as climate change or social justice is key to advancing the sustainability agenda.

But what does a successful ‘deliberation’ entail? For Dryzek (2009), a successful deliberation should include a representative range of perspectives (inclusiveness), it should respect every participant’s opinion in a non-coercive and reciprocal way (authenticity) and have an impact on collective decisions and social outcomes including policy changes (consequentiality).

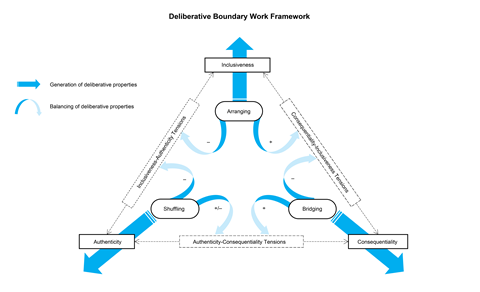

At a time of ESG backlash, it is useful to apply these definitions when looking at deliberative boundary work to sustainable finance. This term applies, broadly speaking, to who is included in a deliberation, what timeframe they are given (arranging); how is the deliberative process run (shuffling); and how the space of a deliberative process is connected to other spaces (bridging). Our research demonstrated how deliberative boundary work can help to balance tensions that are intrinsic to simultaneously achieving the three deliberative properties (inclusiveness, authenticity and consequentiality).

Our research looked at the 2016 European Commission’s High-Level Expert Group on sustainable finance (HLEG-SF). This group was tasked with recommending the shape that sustainable finance regulation should take. These recommendations became the successful backbone of the 2018 European Commission Sustainable Action Plan (including the European Taxonomy and SFDR). We focused on inclusiveness, authenticity, and consequentiality as a springboard to unpack what made the HLEG-SF deliberation so successful and to theorise how deliberative capacity is generated.

As a result, we created a deliberative boundary work framework that can be put into practice by responsible asset owners and asset managers wishing to further their engagement and stewardship efforts with clients and end beneficiaries.

Figure 1: Deliberative boundary work: A framework

How our research moved the conversation on

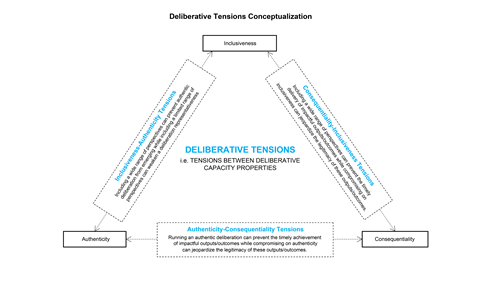

We found it was important to take stock of two things that were overlooked by previous academic research. Firstly, we conceptualised the tensions intrinsic to generating deliberative properties and identified potential trade-offs along the line (for example, selecting diverse types and levels of expertise for more inclusiveness or similar types and levels of expertise for more authenticity):

Figure 2: Deliberative tensions conceptualisation

Second, we demonstrated the importance of thinking seriously about how space and boundaries are constituted by stakeholders to understand how deliberative capacity is generated and balanced via boundary work.

Balancing tensions through boundary work: the HLEG-SF

With the HLEG-SF, the ideal of including the largest number of stakeholders’ perspectives on sustainability finance regulation in the most representative way (inclusiveness) could have easily clashed with the need to have informed and reciprocal debates (authenticity) on the often-technical matter of sustainable finance.

This clash was largely avoided through arranging the spatial-temporal and participation boundaries of the HLEG SF deliberative space. In doing so, the European Commission opted to include a relatively diverse pool of perspectives and educational backgrounds, from traditional finance representatives to NGOs and sustainability advocates such as the WWF. NGO participants and sustainable finance experts were able to include social perspectives that were not on the radar of the European Commission, which initially focused strictly on environmental issues.

The resulting informed and reciprocal discussion decreased inclusiveness-authenticity tensions.

Due to the European Commission’s open-mindedness on the boundaries of its sustainable finance agenda, it ended up attracting a variety of profiles among the 29 HLEG SF participants that were selected from more than 100 applications. In addition, the Commission was strict about delivery timelines. They had just one year to release the final HLEG-SF report in January 2018. These temporal boundaries increased inclusiveness and consequentiality tensions pertaining to the challenge of representing all the experts’ perspectives.

Also noteworthy was how the process was run by the chair, who shuffled boundaries throughout the deliberative process. Aligned with the openness of the Commission’s agenda, the epistemic boundaries —i.e. the range and types of knowledge discussed throughout the deliberation — remained largely open. Participants felt they could be heard, that no perspectives were off the table, including social ones, and that they were encouraged to contribute their opinions on varied subjects from green bonds to high-frequency trading.

The chair purposively experimented with organisational boundaries by avoiding participants working in silo or succumbing to groupthink. Sub-groups were reshuffled throughout, which allowed many participants to change sub-groups and to expand their knowledge on technical subjects, for example, the Green Taxonomy or low-carbon benchmarks. Participants who may have had opposite views on the role of low-carbon benchmarks realised that they could agree on topics like retail investment products and sustainability preferences, for example. Participants were encouraged to contribute their view in written form, which created a sense that all perspectives would be considered and mattered to the outcome.

Eventually, the necessity to deliver the report led to the decision of selecting some participants to oversee the final deliverables. As a result, this created some authenticity-consequentiality tensions that were finally overcome through convincing the participants that their deliberation would produce a legitimate outcome that was faithful to how the deliberative process unfolded.

The HLEG-SF was successful in terms of its ability to produce impactful outputs (in the form of its interim and final reports) and outcomes (in the shape of the EU Action Plan). Our research found that this was largely achieved by the boundary work of bridging, which meant that the group participants connected with external spaces such as European Commission staff, EU parliament representatives, and the media. HLEG-SF participants were encouraged to work closely and debate robustly with the European Commission staff, to write opinion pieces and to debate in their own countries the shape that sustainable finance regulation should take. This created a sense of responsibility and ownership among HLEG-SF participants that helped to ease the unavoidable tensions when some realised at the end of the process that the totality of their ambitions for sustainable finance regulation would not necessarily be covered due to political feasibility.

Meanwhile, the fact that the boundaries with external spaces was relatively porous created some tensions, notably around the question of whether some non-consensual recommendations among the group should be pushed forward from outside the deliberative space, such as the green supporting factor — an approach that aims to stimulate green investments and loans by lowering the cost of capital requirements for such projects. Again, the boundary work of shuffling that generated authenticity throughout the process brought the group to achieve a written consensus of not recommending per se to implement a green supporting factor but leaving the European Commission the leeway to act upon it in future.

Reflecting on the process, not just the end result

Those in the field of sustainable finance tend, for pragmatic reasons, to focus strictly on the ultimate outcome of the European Union sustainable finance regulation. Our research paper is an invitation to reflect on how these sustainable finance regulatory outcomes were achieved through the configuration of deliberative spaces such as the HLEG-SF.

Thinking in a more systematic manner about the highly political role played by the configuration of deliberative spaces is increasingly important at this time of growing ESG backlash. The deliberative boundary work framework we conceptualised in our research can be a useful tool for PRI signatories when they are confronted in their engagement with companies, policy makers and governments or in their stewardship with end beneficiaries.

You can read the original research published in June 2023