By Jean-Baptiste Jouffray (Stockholm University), Beatrice Crona (Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences), Emmy Wassénius (Stockholm University), Jan Bebbington (University of Birmingham Business School) and Bert Scholtens (University of Groningen & University of St Andrews)

Can finance contribute to seafood sustainability? This is an increasingly relevant question given the projected growth of seafood demand and the magnitude of social and environmental issues associated with its production.

Since the 1960s, aquaculture has been the world’s fastest-growing food sector. Rates of fish consumption have increased twice as rapidly as population growth, and fish has become one of the most traded food commodities. In 2018, global fish production reached an all-time high of 179 million tonnes, supplying vital proteins and micronutrients to billions of people.

But this is not unproblematic. The percentage of fish stocks that are within biologically sustainable levels have decreased from 90% in 1974 to 66% today, and the sector is plagued with unsustainable practices, ranging from illegal fishing and habitat destruction to overuse of antibiotics and forced labour. Making sure that seafood is socially and environmentally sustainable has therefore become a key concern for industry, governments, and the general public alike.

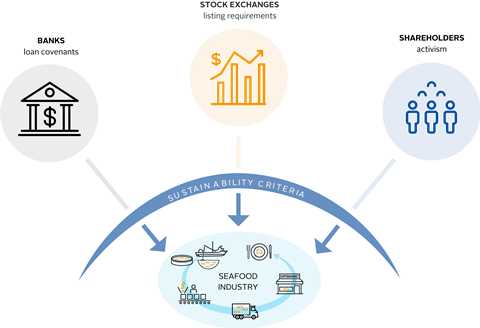

In an article published in the journal Science Advances, we explore what role finance could play in promoting a sustainable seafood industry and where capital can be redirected toward better practices. We found the two most promising levers to be introducing sustainability criteria into bank loan agreements and stock exchange listing rules, while shareholder activism is a less powerful force than might be expected.

Banks hold great potential for promoting sustainability, given their ability to monitor companies in detail and to tailor loan terms. Regardless of a firm’s ownership structure, bank loans dominate external financing in the world’s major economies and are essential to the operations of seafood companies.

By incorporating sustainability criteria into loan covenants and binding companies to sustainable practices, banks could play a prominent role in accelerating transformation toward better practices, not just in seafood but across all ocean-based (and arguably other soft commodity) industries.

For example, in May 2019 the agriculture giant Louis Dreyfus Company agreed with its lenders a US$750 million loan for which the interest rate is linked to the company’s sustainability performance, as measured by a reduction in its carbon dioxide emissions, electricity consumption, water usage and solid waste sent to landfill. If the sustainability rating goes up, the interest goes down, and vice versa.

Likewise, Rabobank recently arranged a US$100 million “green and social” loan with Chilean company AgroSuper, the country’s leading salmon company and the second-largest salmon producer in the world. The loan agreement contains several environmental and social conditions that AgroSuper must comply with, such as a commitment to reduce antibiotic use and increase the number of eco-certifications.

The rapid growth of sustainability-linked loans proves this can be done, but such criteria and incentives need to become the norm rather than the exception. In return, a company’s social and environmental performance will likely feed back to the financier, yielding financial and reputational benefits.

Stock exchanges as gatekeepers

To open its ownership to the public, a firm must get listed on a stock exchange. Companies do so to access capital, gain exposure to broader markets and enhance their brand reputation. This creates another opportunity to scrutinise firms and take sustainability into consideration.

In 2014, for instance, the company China Tuna filed for an initial public offering (IPO) to the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. As part of its risk analysis, the firm indicated that vessels under the Chinese flag had exceeded the catch limits allocated to China year on year but that non-compliance penalties were either non-existent or not upheld. It mentioned that because the Chinese government had not set any quotas with respect to individual fishing companies or vessels, there was no risk of them being held responsible.

Greenpeace filed a complaint saying that China Tuna used outdated data and overlooked environmental risks. They also reached out to China’s Bureau of Fisheries, which strongly condemned the company’s actions as “gravely misleading investors and the international community”, and to Deutsche Bank – the sole sponsor of the IPO – which declined to comment and thereafter suffered reputational damages.

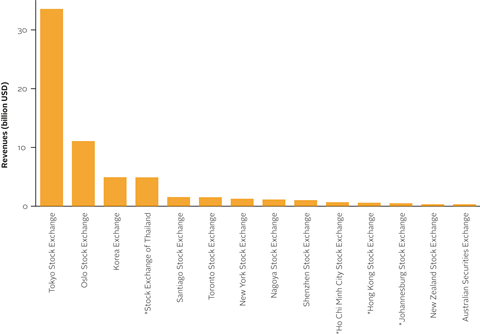

Remarkably, most large publicly listed seafood companies are listed on just a handful of stock exchanges. The Tokyo Stock Exchange alone concentrates 53% of the combined revenue of the world’s top 45 listed seafood companies, while the exchanges of Tokyo, Oslo, Korea and Thailand together account for 86% of revenues. More stringent sustainability criteria in the listing rules of just a few stock exchanges could therefore have big effects on the seafood industry.

Shareholder activism

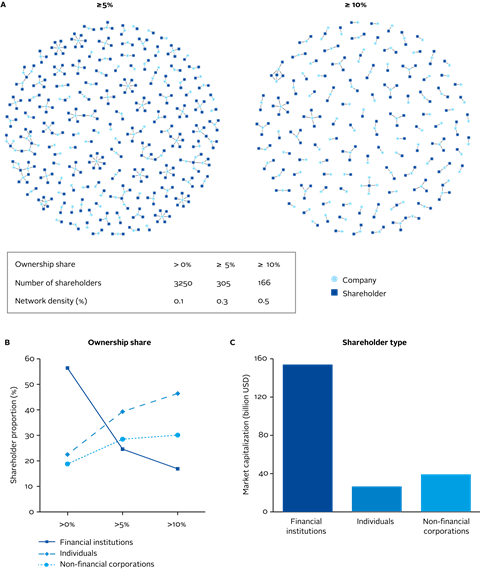

Once a company gets listed, an investor’s impact on corporate decisions is determined by its percentage of stock ownership (and share of voting rights). Shareholder activism is the third financial lever of influence we investigated by analysing more than 3,000 shareholders and 160 seafood firms.

Although it represents an important way to affect company policies, we found its influence may have limitations in the seafood sector. Most large fishing and aquaculture firms are privately owned, and in the publicly listed ones no single investor has substantial shares across many different companies.

Looking at the nature of the shareholders further reveals that the proportion accounted for by financial institutions decreases as the ownership share increases, leaving mainly individuals and non-financial companies as large shareholders. While individuals can be instrumental, they are less susceptible to public pressure than institutional investors such as pension funds or sovereign wealth funds.

The observed pattern of institutional shareholders injecting large amounts of capital into an industry but with little stake in any one company (a conventional risk spreading strategy) creates a “financial commons dilemma” – where powerful financial investors lack the incentives to actively monitor individual seafood firms.

A truly “blue” financial system

Much of the dialogue around sustainable ocean finance to date has focused on development finance, impact investment or the creation of new financial instruments, such as blue bonds. However, while offering much-needed finance streams, these represent only a small proportion of the financial capital supporting the blue economy.

As pressures on the ocean mount, what is missing are norms and regulations that can push for systemic change in the mainstream finance sector and ensure a truly “blue” financial system, where sustainability criteria are systematically integrated into traditional financial services. This would also improve the effectiveness and efficiency of financial institutions with respect to the materiality of nonfinancial information.

Crucial to this process is the disclosure by seafood companies of their non-financial activities and performance, and the need to independently audit the information to ensure its validity and reliability. Where it is not yet the case, national and international regulation regarding financial reporting and accounting must therefore be expanded to also include non-financial information. Governments should enforce this type of reporting by making its requirements on par with those of financial accounting and reporting standards.

The COVID-19 crisis might well offer a unique opportunity to build back better and transition to a sustainable blue economy – by strengthening ocean health and ecosystem integrity to ensure long-term social and economic resilience. Mobilising mainstream finance at the pace and scale that is needed will be decisive.

Read the full paper here.

This blog is written by academic guest contributors. Our goal is to contribute to the broader debate around topical issues and to help showcase research in support of our signatories and the wider community.

Please note that although you can expect to find some posts here that broadly accord with the PRI’s official views, the blog authors write in their individual capacity and there is no “house view”. Nor do the views and opinions expressed on this blog constitute financial or other professional advice.

If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected].