By Rajna Gibson Brandon, ECGI, University of Geneva, Philipp Krueger, Geneva Finance Research Institute, Nadine Riand, Swiss Finance Institute, and Peter S. Schmidt, Geneva Finance Research Institute

A variety of professional data providers construct and sell quantitative metrics of firms’ environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance. These ratings (or scores) increasingly shape the investment decisions of institutional investors. Gibson et al. (2020) find that more than half of the institutionally owned equity is now held by investors who have signed the Principles for Responsible Investment and thus need quantitative ESG assessments to implement their responsible investment strategies.

Unlike credit ratings, ESG ratings are most often created relying mainly on non-standardised information. The construction of these ratings is not regulated and methodologies can be opaque and proprietary, leading to substantial divergence (see Mackintosh, 2018).

Despite the increasing relevance of ESG ratings, there are relatively few large-scale studies examining the nature and consequences of ESG rating disagreement. While some research on why ratings diverge is beginning to emerge (see, for example, Berg et al. 2019 or Christensen et al. 2019), it is still not well understood whether there are financial or other consequences from ESG rating disagreement.

In our paper, ESG rating disagreement and stock returns, we address this issue by building on prior academic research studying the origins and consequences of differences in opinions in financial markets.

We document the multi-faceted implications of ESG rating disagreement on stock returns and thus on costs of capital for firms’ management and responsible investors.

We quantify the magnitude of ESG rating disagreement using ratings from six well-known providers; we conduct statistical analysis to better understand which firms’ characteristics explain rating disagreement and whether the latter is higher or lower for certain types of firms or in certain industries and most importantly, we study the financial consequences of the disagreement by examining its relationship with stock returns.

We focus on S&P 500 firms between 2013 and 2017 and use ESG ratings data from six prominent providers: Asset4 (now Refinitiv ESG), Sustainalytics, Inrate, Bloomberg, MSCI KLD, and MSCI IVA.

Previous research has typically focused on either studying disagreement among financial analysts about a firm’s future earnings, or disagreement among credit rating agencies about a firm’s credit quality.

ESG ratings are different from both earnings forecasts and credit ratings in many respects. Market participants learn about the true realisations of earnings through audited quarterly or annual financial accounts.

In contrast, investors rarely learn about the true ESG performance of companies since there are few prescriptive, standardised, audited and among all – comparable – ESG disclosures. Thus, absent of large scandals such as Volkswagen’s Dieselgate or the BP oil spill, market participants cannot observe whether a company has good or bad ESG policies.

In addition, the methodologies used to construct ESG ratings are not as well established and standardised as, for instance, models used to forecast the credit quality of companies.

How big is ESG rating disagreement really?

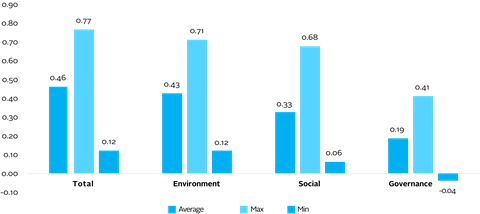

In our analysis, we find substantial disagreement between ESG rating providers. We calculate pairwise correlations between all six data providers for the total ESG rating and separately for the E, S, and G components.

In Figure 1, we report the average, minimum, and maximum pairwise correlations. While the average pairwise correlation for the overall ESG and the environmental rating across providers is 0.46 and 0.43, we report smaller numbers – that is more disagreement – for the social and governance ratings, namely 0.33 and 0.19.

Figure 1 also reveals that some data providers disagree more than others. For example, the minimum and maximum pairwise correlation in the total ESG rating is 0.12 and 0.78 respectively. The reported figures about the magnitude of disagreement – and the relative ordering of disagreement, that is lowest for E and highest in G – are in line with other contemporaneous studies (e.g. Labella et al 2019).

Does ESG rating disagreement correlate with observable firm characteristics?

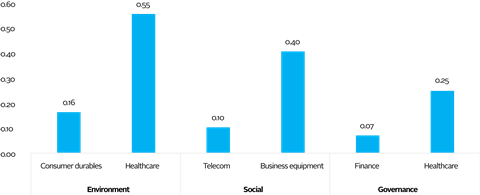

The next objective of our study is to gain a better understanding of whether ESG rating disagreement is higher for certain firms or industries. We relate our measures of disagreement to observable firm characteristics: firms with higher profitability have lower rating disagreement, whereas firms without a credit rating and a higher market capitalisation are subject to higher ESG rating disagreement.

We also explore whether disagreement varies across industries. In Figure 2 we report the industries with the highest and lowest ESG rating disagreement by category. We find that rating disagreement about the environmental dimension is lowest in the healthcare sector. When focusing on the governance dimension, we find that rating providers disagree most about governance in the finance industry: the average correlation is essentially zero.

What are the implications of ESG rating disagreement?

While the prior analyses were relatively exploratory in nature, we build on existing theoretical finance research to develop two competing hypotheses as to how stock returns should relate to ESG rating disagreement. The risk-based hypothesis is based on the idea that higher ESG rating disagreement should result in higher future stock returns because firms with higher disagreement are riskier and investors need to be compensated for the additional risk they are taking by investing in high-disagreement stocks.

Under the competing view, the optimism-bias hypothesis, higher disagreement results in lower future returns, mainly because investors are too optimistic initially about high-disagreement stocks. Investors believe that a firm’s true ESG performance is best captured by the most optimistic ESG rating, which leads to overvaluation of the stock today and lower future returns.

Recent research suggests that firms’ ESG ratings and a country’s legal origin are related (Liang and Renneboog, 2017). When testing the risk-based and optimism-bias hypotheses, we ask whether the link between legal origin and ESG performance carries over to the legal origin of the ESG rating providers themselves.

We divide rating providers into two groups; those with a civil law background and those with a common law background. Based on the idea that firm governance in civil law countries is more stakeholder oriented, we conclude that for the optimism-bias hypothesis, disagreement among civil law raters should be more important for the social dimension.

In contrast, disagreement among common law rating providers about the governance rating should be more informative, mainly because governance in common law countries is more shareholder-centric.

We test our two hypotheses for the overall ESG rating and separately for the three E, S, and G. We find that ESG rating disagreement affects subsequent stock returns in an intricate way. More specifically, we observe that for environmental rating dispersions, the risk-based hypothesis is validated: firms with high dispersion in the environmental rating have higher future returns.

In contrast, when it comes to disagreement about the social and governance ratings, the optimism-bias hypothesis is validated: firms for which civil law-based data providers disagree about the social rating tend to have lower subsequent stock returns, as do firms rated on governance by common-law based providers.

Our analysis has important implications for firm managers by emphasising that their future cost of capital is directly influenced by ESG ratings’ disagreement. Our results also have significant consequences for responsible investors who rely on one or more ESG rating sources. By ignoring the impact of disagreement on future stock prices, responsible investors fail to factor in the potential pricing implications on the performance of their investment strategies.

This blog is written by academic guest contributors. Our goal is to contribute to the broader debate around topical issues and to help showcase research in support of our signatories and the wider community.

Please note that although you can expect to find some posts here that broadly accord with the PRI’s official views, the blog authors write in their individual capacity and there is no “house view”. Nor do the views and opinions expressed on this blog constitute financial or other professional advice.

If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected].

References

Berg, F., Kölbel, J. F. and Rigobon, R.: 2019, Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. Working Paper

Christensen, D., Serafeim, G. and Sikochi, A.: 2019, Why is Corporate Virtue in the Eye of the Beholder? The Case of ESG Ratings. Working Paper

Gibson, R., Glossner, S., Krueger, P., Matos, P. and Steffen, T., 2019. Responsible Institutional Investing Around the World. University of Geneva and University of Virginia

Liang, H. and Renneboog, L.: 2017, On the foundations of corporate social responsibility, The Journal of Finance 72(2), 853–910

Mackintosh, J.: 2018, Is Tesla or Exxon more sustainable? It depends whom you ask, Wall Street Journal. URL: https://on.wsj.com/2MQCC4m

LaBella, M.J., Russell, J. and Novikov, D., 2019. The devil is in the details: the divergence in esg data and implications for responsible investing. Research paper QS Investor