By Jacquelyn Humphrey, University of Queensland, Shimon Kogan, IDC Herzliya & Wharton, Jacob Sagi, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Laura Starks, University of Texas at Austin

ESG investments have experienced phenomenal growth in the last decade, and this trend is unlikely to abate in the coming years. Survey evidence shows that millennials, who will experience a significant intergenerational transfer of wealth in the future, demonstrate strong demand for ESG products.[1]

Baker, Hollifield, and Osambela (2020) argue that the ESG investment phenomenon cannot be reconciled with neoclassical investment theory, which proposes that investors care only about the risk and return attributes of an investment.

Their argument implies that an investment’s ESG attributes affect how investors perceive its outcomes. For instance, an investor may be more sceptical of good news about a low-ranking company than about a company that ranks highly on ESG issues. Alternatively, an investor may feel as good about earning 10% on an investment with a low ESG score as they do about earning 5% on an investment with a high ESG score. In the first case, ESG perceptions affect beliefs about possible outcomes, whereas in the second case, the perceptions impact how the outcomes are valued.

This distinction not only suggests how investors make their decisions, it also has implications for how corporations might respond to these preferences. Suppose that ESG perceptions work mostly by impacting beliefs (i.e. how investors process information). Then improving its transparency on ESG issues might be as beneficial for a company that scores low on these attributes as it would be for it to improve its ESG score. This would not be the case if, on the other hand, firms with low ESG scores are simply perceived as being less valuable.

Experiment results

We study this question through an experimental approach, which allows us to examine the causal relationship between ESG perceptions and investment decisions. The results of this experiment, detailed in our paper, demonstrate that ESG perceptions work through both the valuation and belief channels, with the first having a substantially stronger effect. We find that:

(i) ESG information has a far greater impact on investors’ outcome valuations than their belief formations, and

(ii) the impact is asymmetric – the negative impact on outcome perceptions of poor ESG scores is much greater than the positive impact of good ESG scores.

In our experiment, which is based on the framework of Kuhnen (2015), we ask participants to make a series of investment decisions. After completing the experiment, participants are paid according to their earnings in one of the series’ investment decisions, which is randomly selected.

In the first series of trading decisions, participants choose how to divide their money between a risky stock and cash as they learn about the profitability of the stock. The stock could offer a high pay-out or a low pay-out. Participants do not know which type of stock they face, only that prior to the first of six investment decisions, a computer will randomly choose whether the stock has the low or the high pay-out, with a 50/50 chance.

Participants make their stock-allocation decision and are then told whether the stock doubled or halved in value. We then ask them to estimate the probability that they are facing the high-paying stock. They then repeat the allocation decision, see the stock pay-out, and report a revised probability estimate. The process is repeated six times. We call this series of decisions the neutral series, as there is no ESG information. The purpose is to ascertain a benchmark against which to compare participants’ subsequent investment decisions, when we add ESG information.

We next present participants with a list of six charitable organisations and ask that they choose one to which their trading profits will be linked. Participants then face two additional series of trading decisions. In one series, the researchers donate an amount equal to participants’ stock investment profits to the chosen charity. We call this the positive series. In the other, the researchers deduct an amount equal to the stock investment profits from the charity. We call this the negative series. We randomise whether participants face the positive or the negative series first.

Importantly, the researchers – and not the participants – make the payments to the charity. This means that participants’ possible pay-outs and the likelihood they are facing the high-payoff stock are the same in the neutral series as in the positive and negative series. The only aspect that varies across the series is whether the researchers make payments to, or deduct funds from, participants’ chosen charities. If ESG information is not pertinent to the investors, no difference should be seen in their allocations or probability assessments across the neutral, negative, and positive series.

We are interested in two aspects of the participants’ responses. First, keeping constant their assessment of the probability that the stock is high or low paying, do participants allocate more or less investment to the risky stock if the pay-out will affect the researchers’ payments to their chosen charity? Second, given the same information history for the stock, do participants provide different probability estimates if they are in the negative or positive series?

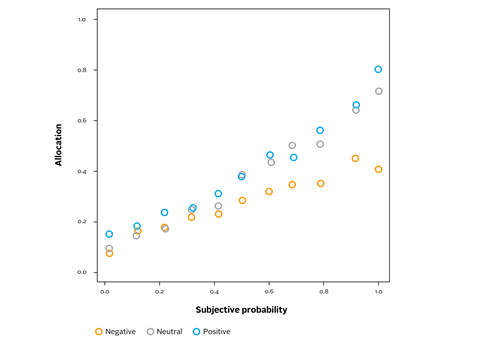

Figure 1 shows average allocations to the stock, grouped by perceived probabilities. The x axis denotes the probability assessment that the stock offers a high pay-out.

The black circles show the neutral series outcomes, where there is no ESG information. We see that the allocations increase with the probability estimates. This makes sense: as the perceived probability of facing a high-paying stock increases, participants invest more in the stock and less in cash because they expect a higher return. The green circles show allocations under the positive series and the red circles under the negative series. Although the allocation in the positive series is slightly higher than in the neutral, the difference is very small. Regression analysis shows that allocations between the neutral and the positive series do not differ significantly.

The pattern of the red circles, however, shows increasingly lower allocations in the negative series as the probability estimates increase. Under the negative series, the higher the pay-out of the stock, the more the researchers will deduct from the charity’s payments. That is, by reducing their allocation to the stock, participants decrease the deduction to the charity but also reduce their own earnings. The figure shows that participants are averse to hurting the charities and become increasingly so as the likelihood of a large deduction grows – even to the detriment of their own pay-outs. This establishes that negative ESG attributes have a significantly greater impact than positive ESG attributes on outcome perception.

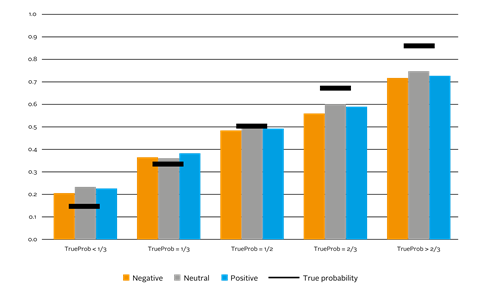

Figure 2 shows participants’ probability estimates – their perceptions of the likelihood that the stock will offer a high pay-out. We group the estimates based on the true likelihood: below one-third, exactly one-third, exactly half, exactly two-thirds, and above two-thirds. The black lines show the actual probabilities, and the vertical bars show participants’ estimates in the different treatments.

The figure captures some interesting patterns in participants’ probability estimates. In line with what we know from prior studies, estimates are biased towards half: too high in the case where the actual probability is less than half and too low if the actual probability is greater than half. (e.g., Tversky and Kahneman, 1992; Abdellaoui, et. al., 2011; Kuhnen, 2015).

What we are interested in, however, are the differences in perceptions across the treatments. Participants seem to think they are less likely to face the high-paying stock during the negative series, even though the probabilities are the same as in the neutral or positive series. This indicates that including negative ESG information in the decision-making process appears to affect participants’ beliefs.

Implications

Our study demonstrates that ESG attributes most profoundly influence outcome perception, but in an asymmetric way. While participants in our experiment responded strongly to negative ESG characteristics, we find less evidence of a response to positive ESG characteristics. This is consistent with the fact that the majority of ESG funds (in the US) use negative screening, often in combination with other approaches such as positive ESG tilts.

The results are also consistent with existing literature documenting a substantial discount for sin stocks (Hong and Kacperczyk 2009; Luo and Balvers 2017). In addition, our findings lend support to the theoretical assumption that investors’ objectives directly incorporate ESG preferences (e.g., Baker, Hollified and Osambela, 2020; Heinkel, Kraus and Zechner, 2001; Oehmke and Opp, 2020; Pastor, Stambaugh and Taylor, 2020; Pedersen, Fitzgibbons, Pomorski, 2020).

Our results have policy implications. The disproportionate (and negative) influence of negative ESG attributes suggests that investors may value ESG harm reduction by firms much more than ESG benefit creation.

Download the full version of our paper.

This blog is written by academic guest contributors. Our goal is to contribute to the broader debate around topical issues and to help showcase research in support of our signatories and the wider community.

Please note that although you can expect to find some posts here that broadly accord with the PRI’s official views, the blog authors write in their individual capacity and there is no “house view”. Nor do the views and opinions expressed on this blog constitute financial or other professional advice.

If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected].

References

[1]See, for example, https://pewrsr.ch/2Op4i3b; https://go.ey.com/2XvjCiP; and https://bit.ly/2O1r5mS.

Abdellaoui, M., A. Baillon, L. Placido, and P. Wakker (2011). The rich domain of uncertainty: Source functions and their experimental implementation, American Economic Review 101, 695-723.

Baker, S.D., B.Hollifield, and E. Osambela (2020). Asset prices and portfolios with externalities. Unpublished working paper.

Heinkel, R., A. Kraus, and J. Zechner (2001) The effect of green investment on corporate behaviour. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 36, 431-449.

Hong, H. and M. Kacperczyk (2009). The price of sin: The effects of social norms on markets. Journal of Financial Economics 93, 15-36.

Kuhnen, C. (2015). Asymmetric learning from financial information. Journal of Finance 70, 2029-2062.

Luo, H. and R. Balvers (2017). Social screens and systematic investor boycott risk. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 52, 365-399.

Oehmke, M. and M. Opp (2020) A theory of socially responsible investing. Unpublished working paper.

Pastor, L., R. Stambaugh, and L. Taylor (2020) Sustainable investing in equilibrium. Journal of Financial Economics, forthcoming.

Pedersen, L., Fitzgibbons, and Pomorski (2020) Responsible Investing: The ESG-Efficient Frontier. Unpublished working paper.

Tversky, A., and D. Kahneman, (1992). Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 5, 297-323.By