By Francesca Arnaboldi, Università Degli Studi Di Milano, Barbara Casu Lukac, CASS Business School, Angela Gallo, CASS Business School, Elena Kalotychou, Cyprus University of Technology and Anna Sarkisyan, Essex Business School, University of Essex

Can gender-diverse boards play a role in preventing costly bank misconduct episodes? Our findings suggest that greater female representation significantly reduces the frequency of misconduct fines, equivalent to savings of $7.48 million per year. Female directors are more influential if they reach a critical mass and are supported by women in leadership roles. The mechanism through which gender diversity affects board effectiveness in preventing misconduct stems from the ethicality and risk aversion of the female directors, rather than their contribution to diversity.

In recent years, larger numbers of scandals and fraud episodes have led to the world’s largest banks being hit with an unprecedented number of misconduct fines, amounting to over £330 billion between 2012 and 2018. The incidents reflect the harm suffered by those who deal with the banks and represent a financial and reputational threat to individual financial institutions as well as the broader financial sector.

Preventing bank misconduct is a top priority for international regulators and policymakers and several rules aiming to offer solutions through better regulation or enforcement were recently enacted. There are several challenges that lawmakers and regulators face in this context, however: regulatory reforms might not be effective without changes in bank corporate culture. To address a potentially toxic culture in financial services, regulators have emphasised increased diversity. The underlying idea is that the tone at the top shapes a firm’s conduct and ethical culture and that more diverse boards, with an increased presence of women, would positively affect company governance.

In recent years there have been several high-profile campaigns aiming to increase female representation on company boards. Examples include the Hampton-Alexander Review in the UK, which reports an increase in the proportion of women on FTSE100 boards. However, the number of women in leadership positions (CEO or chairperson) has scarcely changed and many companies have only one woman on the board. Countries such as France, Italy, and Sweden have gone a step further, introducing mandatory gender quotas. While some progress has been achieved, there is still a long way to attaining gender balance in corporate governance.

Can gender-diverse boards play a role in preventing costly misconduct episodes?

We consider the fines issued by US regulatory bodies on European listed banks in the post-crisis period (2007-2018), which relate to misconduct events such as tax evasion, money laundering, market manipulation, and fraud. The influence of gender diversity on boards’ decisions can be explained as follows: (i) improved monitoring (Adams and Ferreira, 2009); (ii) a broader set of skills (Li and Wahid, 2017), and (iii) increased social responsibility and a more ethical perspective (Cumming et al., 2015).

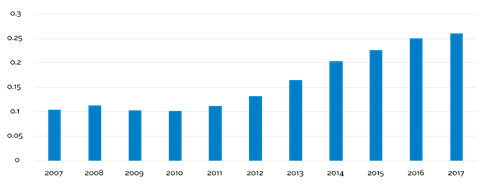

Based on board-related information for all listed European banks, we find that female representation gradually increased from an average of 10.4% in 2007 to 26.1% in 2017. The presence of female leaders also shows an upward trend during the sample period: female CEOs increased from only 1.5% in 2007 to 7.9% in 2017. Nevertheless, banks’ boardrooms remain male-dominated.

Establishing a causal relationship between board diversity and bank misconduct is challenging. Because of political connections, lobbying activities, or concerns about the financial stability of the domestic banking system, regulatory agencies might be vulnerable to regulatory capture (Stigler, 1971), making them less impartial and objective in imposing sanctions on domestic banks. We exploit the fact that US regulators can impose fines not only on banks operating in the US, but on all transactions that pass through the its financial system to US and non-US persons, entities, and institutions. To the extent that board members in our sample of European listed banks have no or weak influence on the outcome of US regulatory investigations, our empirical set-up allows us to mitigate regulatory capture bias.

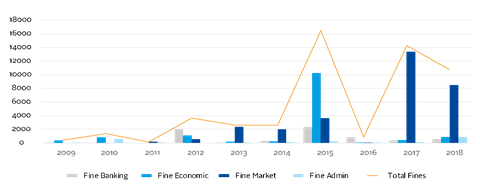

As shown in Figure 2, US regulators hit foreign financial institutions particularly hard following the crisis: European banks have been fined four times more than their US counterparts, representing 77% of the total fines levied by US regulators since 2008 (Fenergo, 2018).

In our empirical analysis, we employ a statistical model to relate the frequency of misconduct fines to board gender diversity. We find that a larger presence of women on the boards of directors is associated with fewer misconduct fines: for the average change in the proportion of women in our sample, the number of fines decreases by a fraction of 0.27, all else being equal. The effect is economically significant: representing an annual saving of $7.48 million. The evidence persists when controlling for other potential drivers of bank misconduct such as bank size, risk, profitability, growth opportunity, CEO and board features and country-level controls such as the GDP growth and a proxy of economy development. These results seem to support the view that increased gender diversity helps foster a better corporate culture, thus reducing conduct risk. Our analysis also highlights that women have a more significant role in curbing misconduct when the number of female directors reaches a critical mass (where there are at least three women) and are supported by women in leadership roles.

Concluding remarks

Our results support the view that gender has a significant effect on the attitudes of managers towards business ethics but also risk-taking: gender diversity improves bank culture and reduces conduct risk. We also find that women are more influential in countries with higher gender equality. While most European countries have made considerable progress in terms of gender equality in areas such as educational attainments and health, with scores very close to 1 (equality); substantial inequality remains in areas such as economic participation and political empowerment, according to The Global Gender Gap Report. One of the biggest challenges lies in changing stereotypes and bias in society, highlighting the importance of government and regulatory initiatives aimed at fostering gender diversity.

This blog is written by academic guest contributors. Our goal is to contribute to the broader debate around topical issues and to help showcase research in support of our signatories and the wider community.

Please note that although you can expect to find some posts here that broadly accord with the PRI’s official views, the blog authors write in their individual capacity and there is no “house view”. Nor do the views and opinions expressed on this blog constitute financial or other professional advice.

If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected].

References

Adams, R. B. and Ferreira, D. (2009) Women in the boardroom and their impact on governance and performance, Journal of Financial Economics 94, 291-309.

Arnaboldi, F., Casu, B., Gallo, A., Kalotychou, E., and A. Sarkisyan (2020) Gender Diversity and Bank Misconduct, WP-CBR-01-2020. https://www.cass.city.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/510975/Arnaboldi_et_al_2020.pdf

Cumming, D., Leung, T.Y., Rui, O. (2015). Gender diversity and securities fraud. Academy of Management Journal, 58 (5), 1572–1593.

Fenergo (2018) A fine mess we’re in. AML/KYC/Sanction Fines. A ten-year analysis (2008-2018). www.fenergo.com

Hampton-Alexander Review, FTSE Women Leaders (2019) Improving gender balance in FTSE Leadership (November 2019). https://ftsewomenleaders.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/HA-Review-Report-2019.pdf

Li N. & Wahid, A.S. (2017). Director Tenure Diversity and Board Monitoring Effectiveness, Contemporary Accounting Research, 35, 1363-1394.

Stigler, G.J. (1971) The theory of economic regulation. The Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science, 2(1), 3-21.

The Global Gender Gap Report (2019), World Economic Forum. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2018.pdf