ESG incorporation in securitised products lags other fixed income sub-asset classes and is in its infancy – largely due to the complex nature of the market. However, investor interest is growing.

The discussion is quickly evolving from why to how, as investors grapple with two problems:

(1) building a rigorous framework for assessing ESG factors in mainstream securitised products and enhancing credit risk assessment beyond traditional fundamental analysis;

(2) promoting standards within the nascent ESG securitisation market – as attested by the rising number of ESG-labelled securitised products[1] – to ensure its veracity.

Key report findings

- Client demand, risk management and a desire to have a more positive environmental and societal impact are driving ESG considerations in securitised products.

- Regulation is also influencing investor behaviour, as lawmakers focus on improving ESG disclosure and standardisation throughout financial markets. Although most changes are occurring in Europe, investors are also monitoring other regions, including the United States.[2]

- Investors’ fixed income ESG policies are expanding, but they are not tailored to securitised products. Most investors are exploring how they can adapt and apply the ESG incorporation practices used with other types of debt instruments to these products.

- Negative screening remains the most widely adopted incorporation approach for European ESG-labelled Collateralised Loan Obligations (CLOs). The legal documentation accompanying them is not harmonised; CLO managers’ ESG evaluation processes are vague; and – for now – little price differential versus mainstream products exists.

- The securitisation market is fast evolving across other products[3] too, with increasing green, social and sustainability issuance. Many deals refer to the International Capital Market Association’s green, social and sustainable principles, respectively, or the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

- A lack of adequate data to conduct ESG due diligence is the main challenge preventing many investors from systematically integrating ESG factors in their securitised products analysis.

The report’s evidence is focused on CLOs. It is easier to scrutinise the ESG factors relevant to their underlying corporate loans than to the various loans that are linked to RMBS, CMBS and ABS, despite the latter products occupying the larger market share.

The PRI will continue to test these findings within the industry and broaden our regional analysis, as the importance of securitised products in sustainable finance is likely to grow. We intend to focus more on RMBS, CMBS and ABS and will expand our research to credit rating agency (CRA) practices. Finally, we will facilitate investor engagement with several stakeholders, including banks, CRAs, ESG information providers, legal counsellors and arrangers.

ESG information wanted by investors

| CLOS | CMBS | RMBS and ABS |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

About this paper

This report explores to what extent investors consider ESG factors when investing in securitised products. It highlights current market practices and the hurdles that need to be addressed for ESG factors to be considered more systematically in the risk assessment and pricing of these products and their underlying assets.

It adds to the fixed income work that the PRI started in 2013, which has expanded from looking at ESG incorporation in corporate and sovereign bonds to private and sub-sovereign debt. [4]

The report focuses on US and European securitised products, whose underlying assets are loans or other types of credit instruments that generate future cash flows, and to which most PRI signatories that report on their investment activities in this asset class have exposure.

It does not cover products that are linked to commodities or financial assets such as equities, security indices, interest rates, foreign currencies and synthetic securitisations. [5] Readers looking to familiarise themselves with private debt more broadly should refer to the PRI’s 2019 report, Spotlight on responsible investment in private debt . Anyone new to responsible investment concepts should refer to the PRI’s series of guides, An introduction to responsible investment .

The paper draws on the experience of advisory committee members and other market participants that were interviewed about their ESG incorporation practices by The Smart Cube (TSC), a consultant appointed by the PRI that also contributed to desk-based research. [6]

Overview of securitised products market

Key messages

- ESG incorporation in securitised products significantly lags other fixed income sub-asset classes.

- The market is evolving with the emergence of ESG-labelled securitised products: European ESG CLOs have proliferated, while the green, social and sustainability-labelled issuance of other products is also developing.

- Investors are looking at how to build frameworks to assess ESG factors across all securitised products and to determine whether ESG-labelled securitised products are genuine.

Through Principles 1 and 3, PRI signatories commit to incorporating ESG issues into their investment decision-making processes, as well as seeking appropriate disclosures from investee entities.

They do so to improve the risk management of their investments, to meet the long-term interests of their beneficiaries and to be better aligned with broader societal objectives.

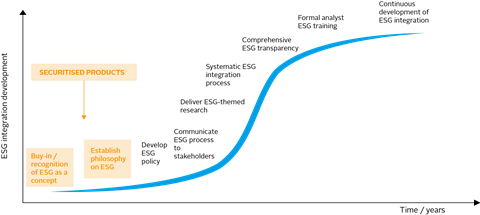

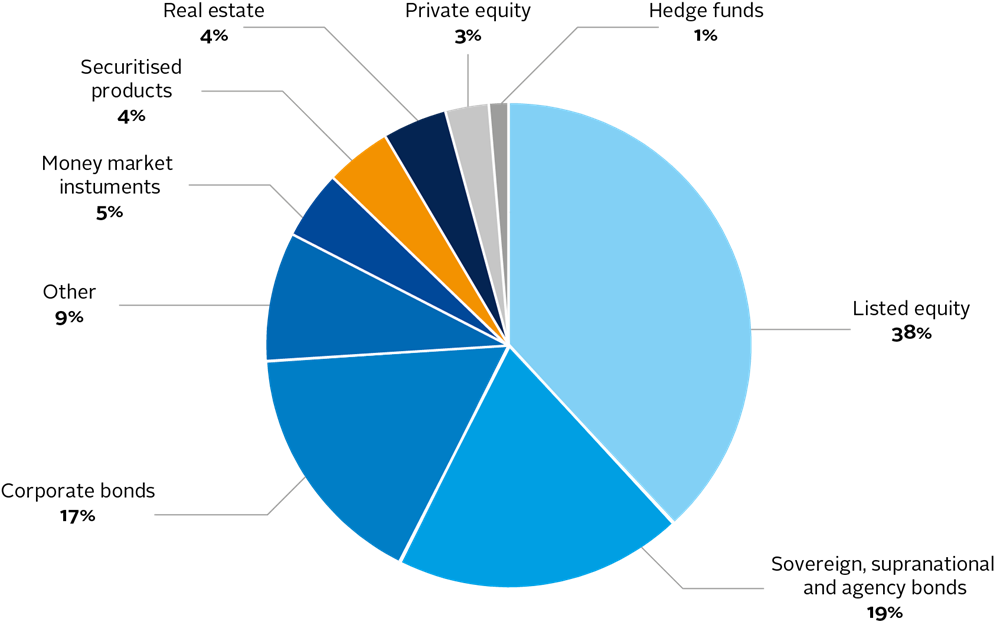

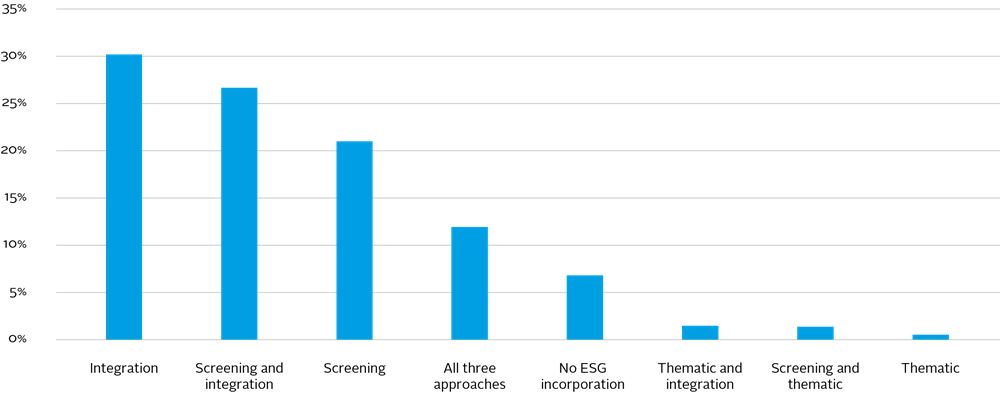

However, ESG incorporation in securitised products significantly lags other fixed income sub-asset classes and is in its infancy (see Figure 1), largely due to the complex nature of the market.

While investors are aware of how important responsible investment is overall, they are grappling with two problems:

(1) How to build a rigorous framework for assessing ESG factors in mainstream securitised products and enhancing credit risk assessment beyond traditional fundamental analysis.

(2) How to promote standards within the nascent ESG securitisation market (as attested by the rising number of ESG-labelled securitised products that have emerged in the last three years – discussed in the Market size and development section) to ensure its veracity.

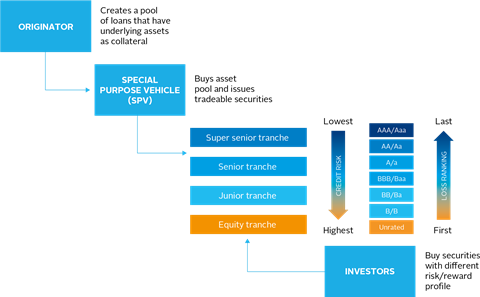

The underlying assets linked to securitised products can vary significantly, from residential and commercial mortgages (RMBS and CMBS, respectively), to pools of corporate loans (CLOs) or consumer products, such as auto loans and credit card receivables, also known as asset-backed securities (ABS).

Some, such as specific corporate borrowers, can be easily scrutinised for ESG factors. Conversely, for loans to large numbers of individuals or non-homogeneous borrowers – in the case of RMBS, CMBS and ABS – it is more difficult, despite these accounting for the largest market share.

Figure 1: ESG incorporation in securitised products is in its infancy

Market size and development

Securitised products have existed since the 1970s, when US government-backed agencies started to repackage and sell off pools of residential mortgages. The market has evolved significantly since then; diversifying across developed and emerging geographies and experiencing various swings in popularity.

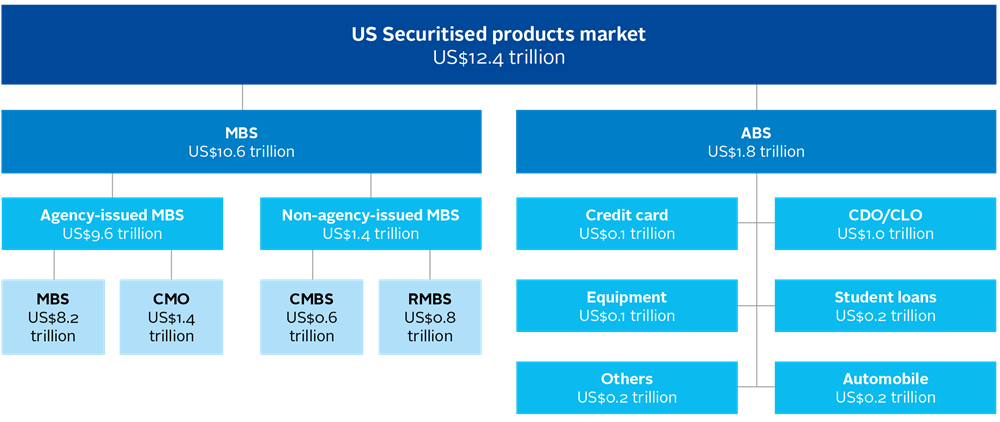

The US securitised product market is the largest in the world, accounting for over 25% of the country’s fixed income market. As of 30 November 2020, it was worth US$12.4 trillion, as measured by outstanding issuance, with agency-issued MBS [7] accounting for the largest share within that (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: US securitised product market breakdown – total outstanding bonds. Source: Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association

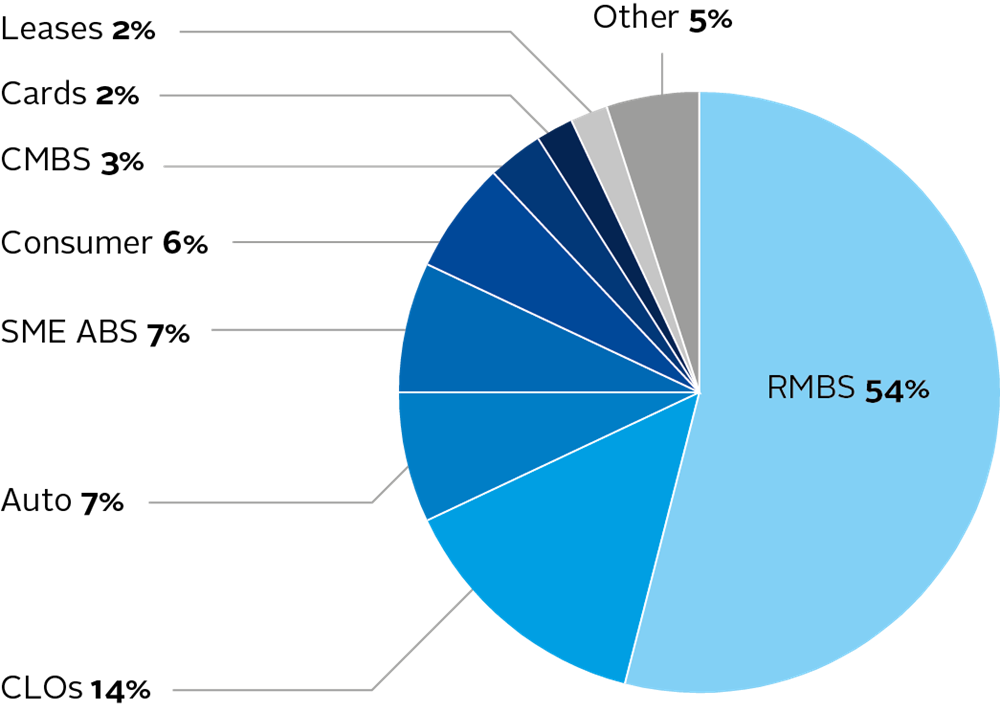

By comparison, the European securitised product market was worth €1.1 trillion (US$1.3 trillion) as of 30 September 2020 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: European securitised products market breakdown – total outstanding bonds. Source: Multiple [8]

Since the global financial crisis, new issuance has contracted, but the market has also transformed significantly, with changes that have important governance implications. New regulation has led to increased disclosure requirements for investors, greater credit support at each tranche level, stricter underwriting criteria for underlying collateral and reduced use of pro-forma underwriting. Collectively, these changes have significantly improved investor protection and transparency.

Over the last few years, ESG-labelled securitised products have also started to emerge. Since the first issuance in March 2018, European ESG CLOs have proliferated (see Figure 4), while the green, social and sustainability-labelled issuance of other securitised products has developed more recently across different jurisdictions (see Figure 5). We analyse some of these products later in the report – see Evidence from European ESG CLOs .

Figure 5: Other types of ESG-labelled securitised products. Sources: Multiple [10]

| Issue date | Profile | Type | Deal name | Deal ticker | Sponsor | Collateral |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30.06.2016 | Green | EUR RMBS | Green Storm 2016 | STORM 2016-GRN* | Obvion | Dutch mortgages financing energy-efficient homes |

| 01.06.2019 | Green | USD Agency CMBS | Freddie Mac Structured Pass-Through Certificates, Series K-G01 | FHMS KG01* | Freddie Mac | US commercial mortgages on multifamily properties with an energy efficiency component |

| 07.11.2019 | Green | AUD RMBS | Pepper Residential Securities Trust No. 25 | PEPAU 25X A1GE* | Pepper | Australian residential mortgages with an energy efficiency component |

| 06.02.2020 | Green | EUR CMBS | River Green Finance 2019 | RGRNF 2020-1 | LRC Real Estate Limited | French commercial mortgage financing an energy-efficient office property |

| 23.10.2020 | Social | GBP CMBS | Sage AR Funding No. 1 | SGSHR 1X | Sage Housing (Blackstone majority-owned) | UK commercial mortgage financing social housing |

| 01.11.2020 | Green | USD CMBS | COMM 2020-CX Mortgage Trust | COMM 2020-CX | DivcoWest and CalSTRS JV | US commercial mortgage financing an energy-efficient life science property |

| 01.01.2021 | Green | USD Agency MBS | Fannie Mae Pool # CA8957 3.06% 30yr | FN CA8957* | Fannie Mae | US residential mortgages on single-family properties with an energy efficiency component |

| 01.01.2021 | Sustainable | USD Agency CMBS | Fannie Mae Multifamily REMIC Trust 2021-M1s | FNA 2021-M1S* | Fannie Mae | US commercial mortgages focused on promoting affordable rental housing |

| 24.02.2021 | Social | GBP RMBS | Gemgarto 2021-1 | GMG 2021-1X | Kensington | UK mortgages with a financial inclusion component |

Developing holistic risk assessment

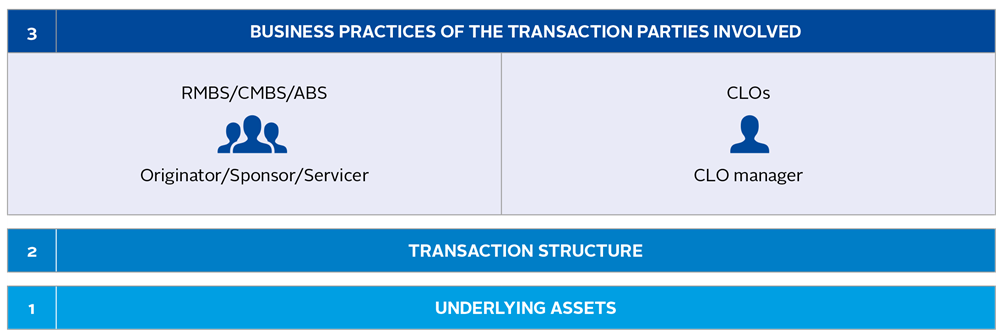

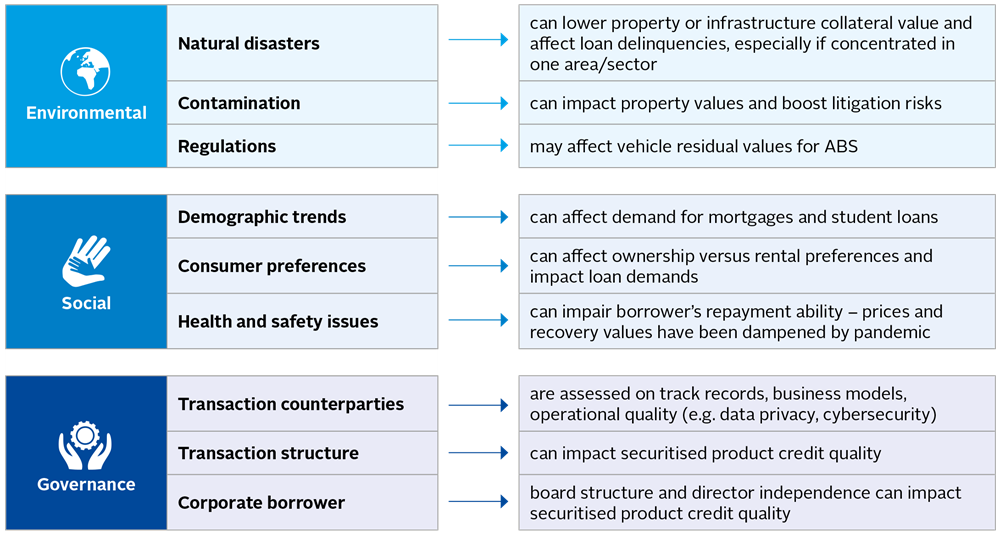

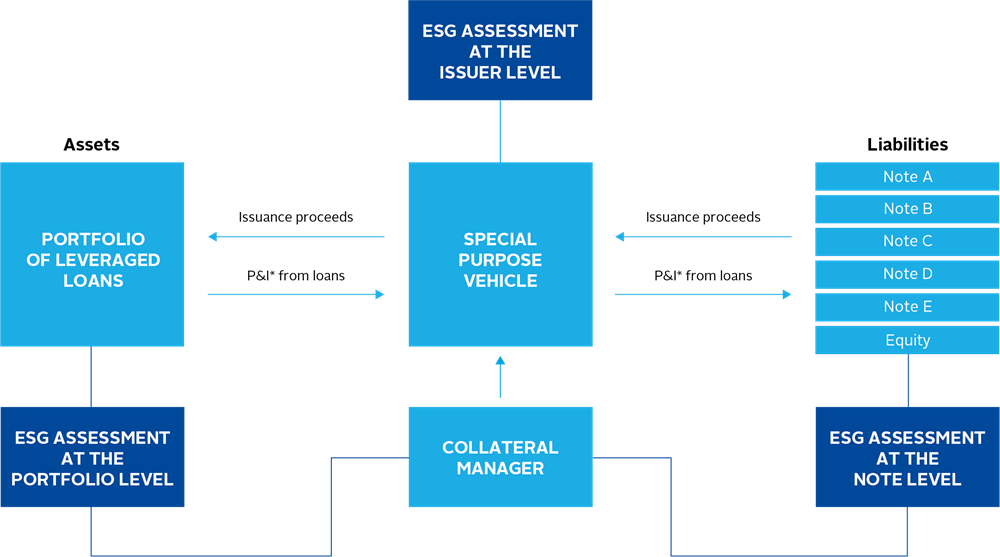

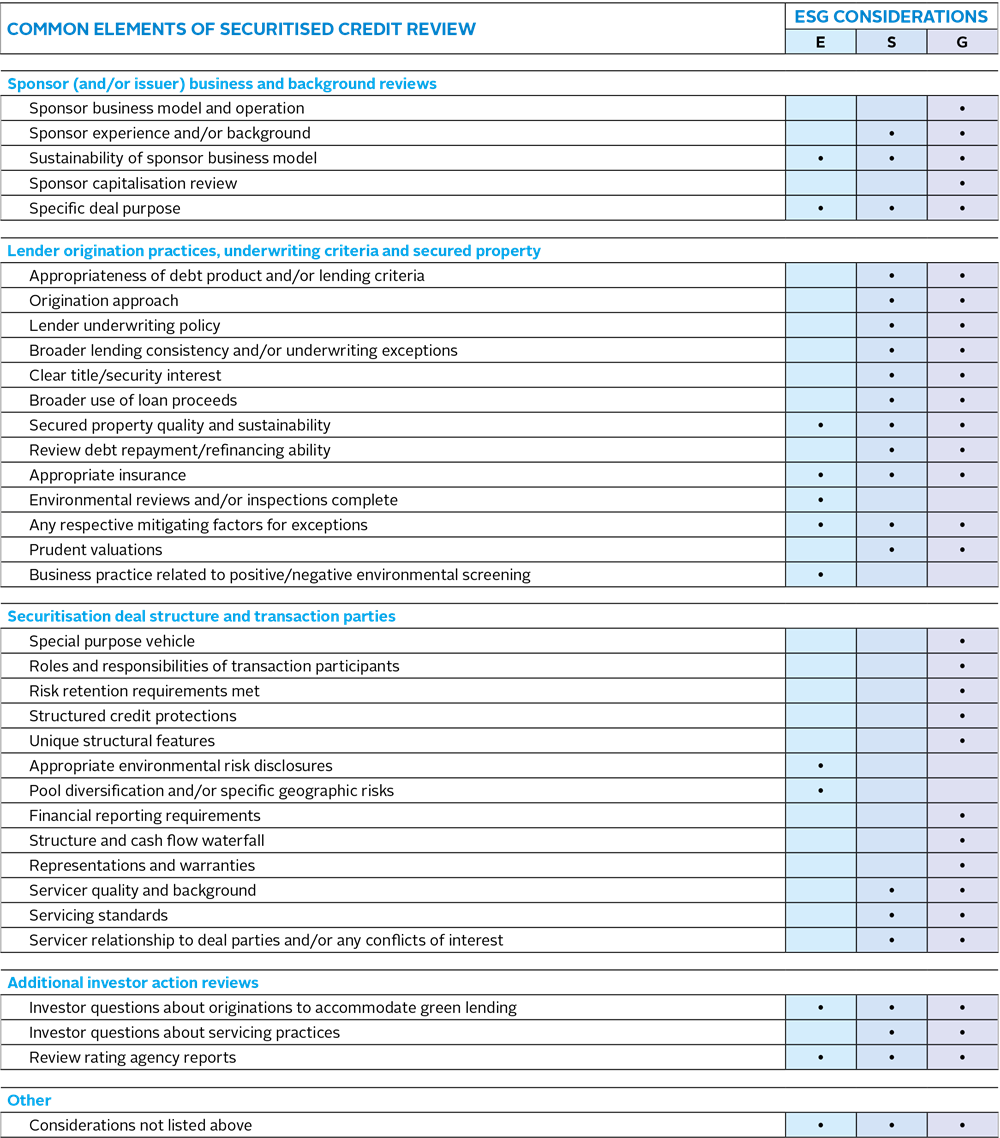

For ESG incorporation in securitised products to be effective, a holistic, multi-pronged approach needs to be developed. It needs to account for their complexity – such as having one transaction party occupying multiple roles (e.g. servicer and originator), or funding private entities, which tend to be less transparent (see Figure 6). [11]

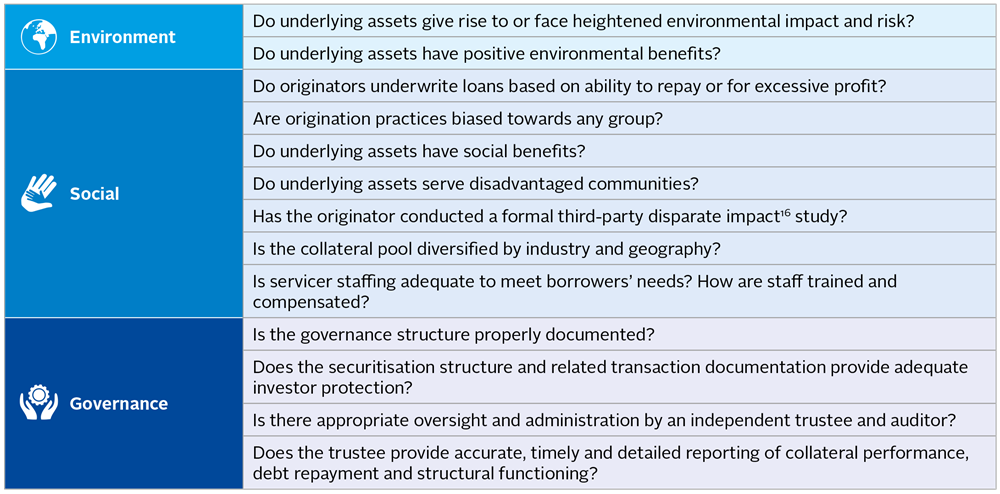

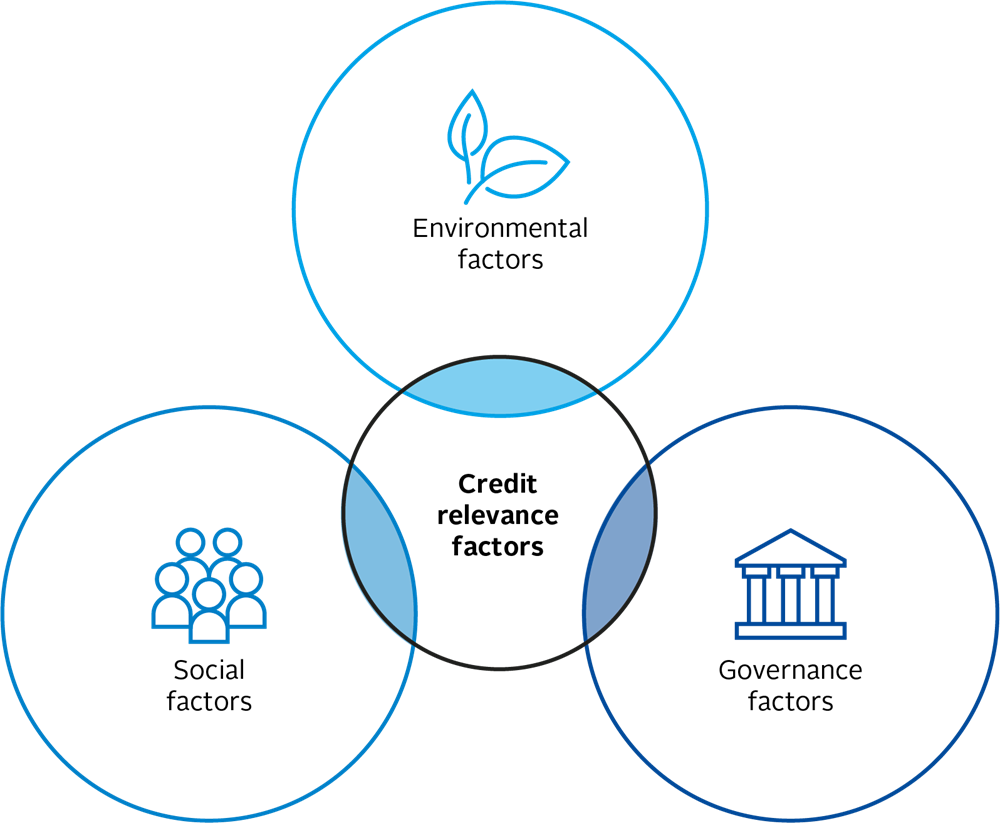

Such an approach would include weighing the underlying assets against environmental and social impacts, while also considering an issuer’s governance practices and the securitisation documents (see Figure 7).

More transparency is needed throughout the investment chain so that investors have the necessary information to perform robust due diligence on securitised products – whether ESG-labelled or not – and can assess how aligned they are with their portfolio objectives and investment strategies (see Figure 8).

“We look very carefully into the originator, the servicer and the various transaction counterparties, as part of our fundamental analysis.”

European investment manager

Figure 6: Simplified multi-pronged ESG assessment in securitised products

Figure 7: ESG factors that can impact securitised products

Figure 8: ESG assessment in the CLO structure

Current ESG practices

Key messages:

- Firms’ ESG policies are increasing but few are tailored to securitised products.

- Client demand, risk management and the desire to have a positive impact are driving investors to start considering ESG factors more systematically in their investment processes.

- Regulation in Europe is another driver but changes in the US and elsewhere are also on investors’ radars.

- There is no meaningful price differentiation between mainstream and ESG CLOs for now.

- Credit rating agencies have started signposting ESG factors in their securitised product rating opinions, but investors note that this needs to improve further.

This section highlights current ESG practices among securitised product investors, based on PRI signatory reporting data and interviews with advisory committee members and other market participants. It focuses largely on the European CLO market. It also briefly addresses the role that credit rating agencies play in securitised product investments.

Common ESG approaches according to PRI reporting

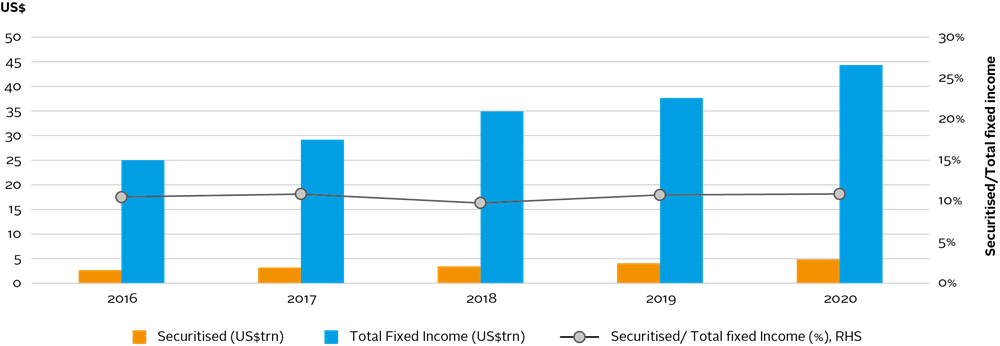

Among PRI signatories, the AUM invested in securitised products has nearly doubled over recent years, from US$2.6 trillion in 2016 to US$4.8 trillion in 2020, but it remains a small share of the overall fixed income assets they report on, which totalled US$44.4 trillion as of 31 March 2020 (see Figures 9 and 10).

Figure 9: Signatory assets invested in securitised products

Figure 10: Signatory assets invested in securitised products vs fixed income

Of the 2000 signatories that reported on their investment activities to the PRI in 2020, only 215 indicated how they incorporate ESG factors into their securitised product investments. [12] Integration and screening approaches – either alone or in combination – were the most popular (see Figure 11). [13] However, as signatories do not specify which securitised products (RBMS, CMBS, ABS or CLO investments) these approaches cover, it is difficult to determine whether this accurately reflects wider trends in this market.

Figure 11: ESG incorporation approaches reported by PRI signatories (based on 215 respondents)

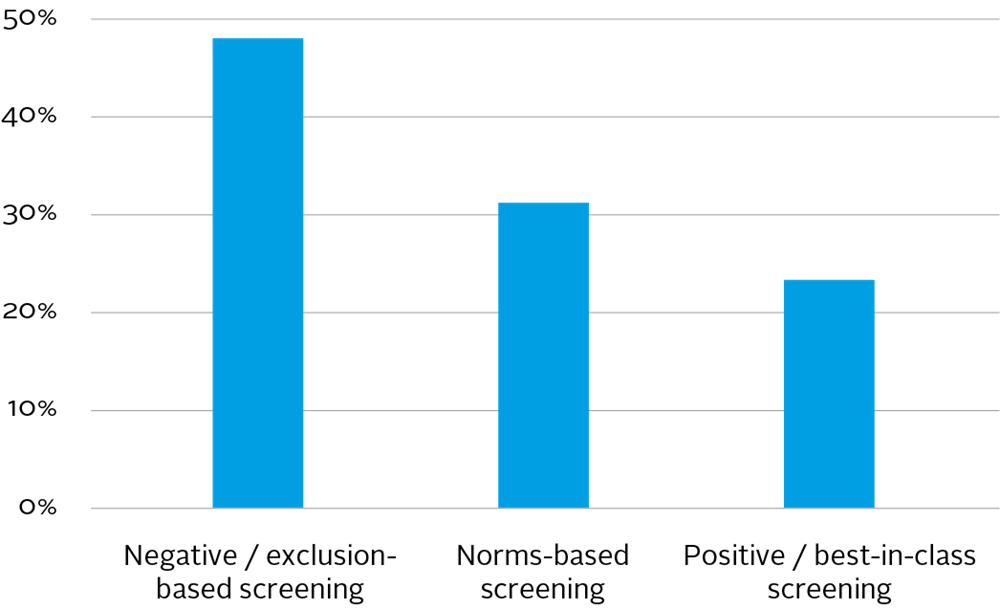

Almost half of the signatories that implement screening use a negative or an exclusion-based approach (see Figure 12), a trend also reflected in our interview findings.

Figure 12: Types of screening conducted for securitised products (based on 143 respondents)

Interview observations

Interview participants

The Securitised Products Advisory Committee and 14 additional market experts were asked to share their current ESG practices and the challenges they face to further their responsible investment approaches. Unless stated otherwise, the questions received responses from 22 organisations of varying sizes. The interviews were conducted in early 2020. Participants are listed in the Acknowledgments. The questionnaire can be found in Appendix 1 .

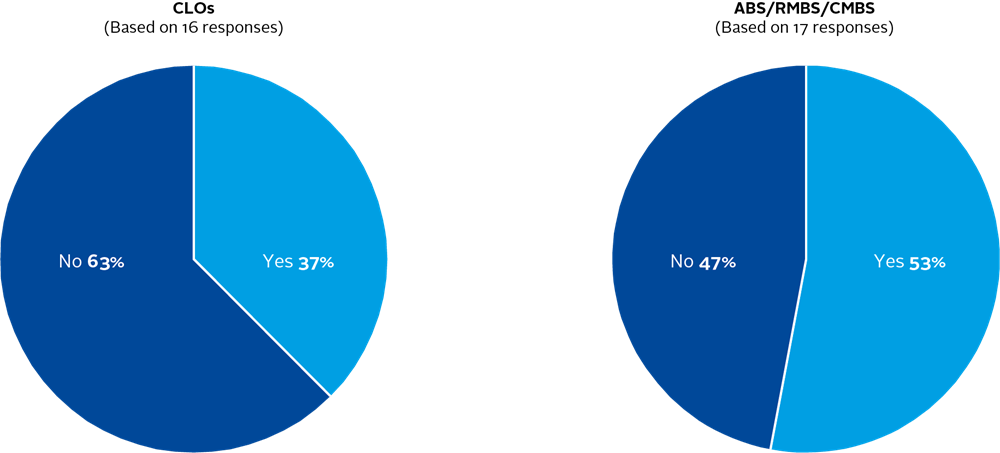

ESG incorporation

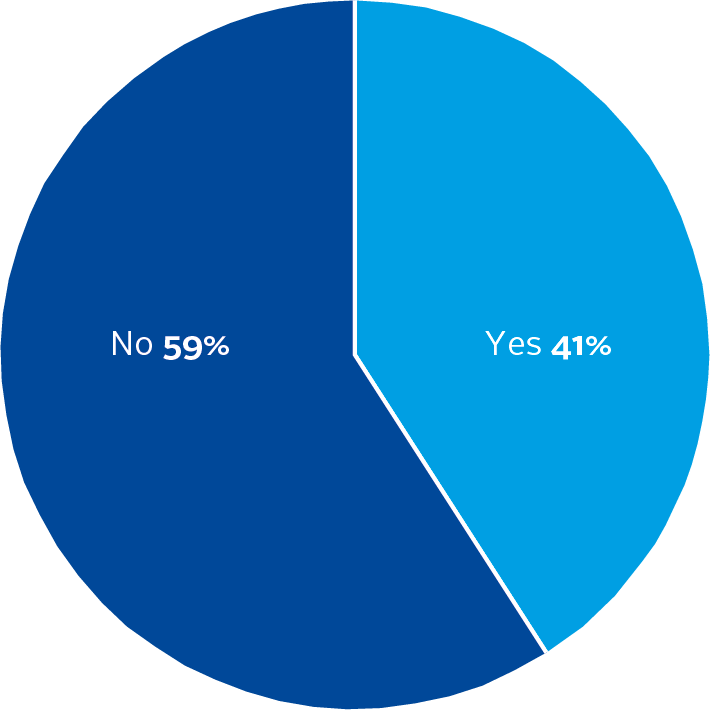

Around 90% of the participants indicated that they have started incorporating ESG factors into their investment decision-making processes systematically. However, this varies considerably in practice, as demonstrated in Figure 13.

Figure 13: Does your firm incorporate ESG factors in its assessment of securitised products?

Whilst screening remains the most common ESG incorporation approach (see Evidence from European ESG CLOs ), a few market practitioners have also started looking at ESG integration practices, such as:

- embedding ESG factors into bottom-up, risk-reward assessments;

- modelling prepayment speeds using external climate risk data;

- conducting scenario analysis based on publicly available ESG data; and

- establishing internal ESG scoring frameworks.

Dedicated ESG team

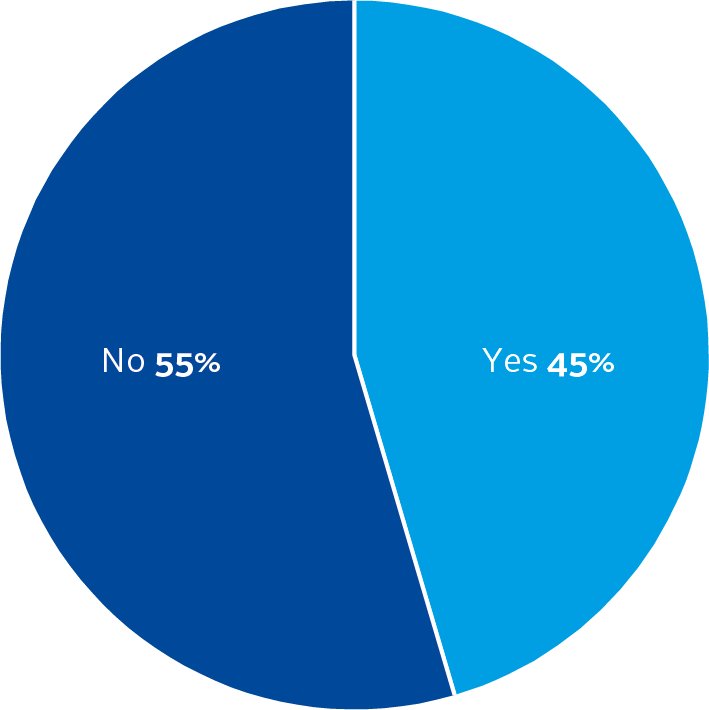

Around 40% of participants have a dedicated team that assesses ESG factors across securitised products, while the majority have an investment team that incorporates ESG factors into traditional analysis (see Figure 14). Some indicated that having a dedicated team has merits, as it allows investment managers to better analyse a range of ESG information. However, the benefit of this arrangement depends on how well that team can influence the investment research and decision-making process.

Figure 14: Does your firm have a dedicated ESG team?

Regardless of the approach taken, there is an increasing appreciation in the investment industry that ESG analysis can complement and enhance traditional fundamental analysis. The more advanced investment managers consulted are building their ESG capacity, recognising that analysts need to be better equipped and have more expertise.

Product-specific ESG policies

Most respondents have not yet established ESG frameworks that are tailored to securitised products. Some have developed ESG-focused principles at a firm level (see Figure 15), while others are exploring how they can adapt and apply some of the ESG incorporation practices used with other types of debt instruments.

Figure 15: Does your firm have a publicly available ESG policy?

Some investors are beginning to create review templates for securitised products to frame risk assessment in a more holistic way, thus laying the building blocks of a systematic ESG approach (see Figure 16). Others are starting to shape their analysis by addressing some of the questions listed in Figure 17.

Figure 16: Example of securitised credit ESG dashboard. Source: TCW

Figure 17: Sample questions included in ESG review template for securitised products

Drivers of ESG incorporation

Although ESG incorporation in securitised products has significantly lagged other fixed income asset classes, the gap may close relatively quickly in the coming months.

PRI signatories’ broader understanding of responsible investment practices continues to grow [15] , while the number of resources available to facilitate ESG incorporation in debt instruments is increasing (see Next steps for more detail).

Mirroring the corporate and sovereign bond space, many interview participants [16] acknowledged that they already include some governance factors in their risk analysis and are now being driven to consider ESG factors more explicitly in their investment processes due to:

• client demand;

• risk management;

• a desire to have a more positive environmental and societal impact; and

• regulation.

Client demand

Just over 50% of interview participants said retail and institutional investors are increasingly seeking securitised products with ESG credentials, echoing a trend seen in equity and fixed income markets a few years ago, where client demand led to a broader uptake of ESG incorporation. [17]

Asset owners now expect investment managers to demonstrate how they are integrating ESG factors in their investment processes, reflected in due diligence questionnaires or requests for proposals that increasingly include dedicated ESG sections. This trend is likely to continue as more asset owners join industry-wide ESG/climate initiatives [18] and seek to develop and improve their own responsible investment practices.

“The investment management industry is not going to invest [resources] in a product that has no demand. We can put more internal resources into ESG products – including securitised products – if we know a group of clients is receptive [to them].”

US investment manager

Risk management

Nearly 50% of participants stated that risk management was driving them to start incorporating ESG factors into their investments. This is positive, as it suggests that ESG factors are no longer perceived as a constraint but are part of investment risk assessment. However, there is still room for improvement – as enhanced risk assessment that includes ESG considerations becomes a more integral part of securitised products analysis and as investors better appreciate the financial materiality of ESG risks. Furthermore, more data is becoming available, making ESG factors more quantifiable.

“We have a fiduciary responsibility to our investors to have and maintain the best risk assessment framework possible.”

US investment manager

Positive environmental and societal impact

Nearly 30% of participants said they want their investments to have a positive environmental and social impact. However, many stated that ESG issues did not impact whether an investment was made, particularly in relation to CLOs, where ESG factors are viewed as tail-risk events rather than forming a part of day-to-day investment decisions (see Figure 18).

Figure 18: Are investments rejected solely based on ESG criteria?

“We can help to put ESG factors on the radar of sponsors by making them part of the criteria considered during credit analysis. We do that in a constructive, not punitive, way – that is why we do not decline investments purely based on an ESG score.”

European investment manager

Regulation

Participants also cited regulation as a factor that is likely to become increasingly important among the drivers behind more systematic ESG incorporation.

Had we conducted our interviews at the start of 2021, regulation would have likely ranked higher. The first provisions of the EU sustainability-related disclosures in the financial services sector regulation (SFDR) came into force in March 2021, as part of the EU Commission’s policy focus on sustainable finance and of the EU’s ambition to be climate-neutral by 2050. Moreover, there are ongoing efforts at the national level. [19] Although these regulatory changes are being spearheaded in Europe, their repercussions will have a wider reach, as all financial market participants wanting to operate in the EU will have to comply.

Participants are also monitoring other regions of the world, especially the United States, where the new administration has been sending positive signals regarding its approach to certain environmental and social issues [20] (for more detail, see Appendix 2 ).

The ramifications of these developments for securitised products are unclear at this stage, but at the very least, they suggest that there could be more regulatory focus on ESG disclosure related to financial instruments.

Evidence from European ESG CLOs

These observations relate to the European CLO market, which many interview participants focused on, as these products lend themselves better to the provision of ESG information, given they are linked to underlying corporate loans. We have supplemented these findings with an analysis of offering documents and a comparison of CLOs, conducted on our behalf by Deutsche Bank. [21]

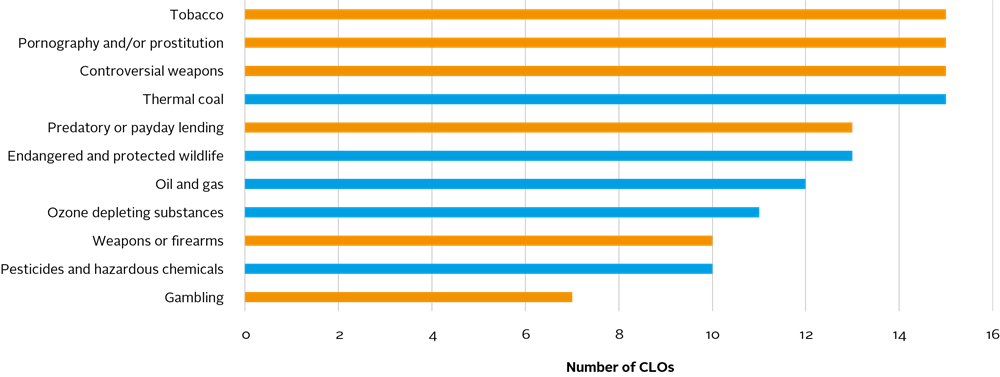

Use of negative screening

Many European CLO transactions use negative screening in the eligibility criteria for the underlying assets, overseen by the CLO manager.

Loans to obligors that are engaged in certain industries or activities – such as tobacco or arms – are excluded from these transactions, typically if they derive more than a certain percentage of revenues from such businesses. Maintaining a firm-level exclusion list, often derived from internal and client-driven criteria that can be further adjusted in individual investment cases, appears to be a common practice followed by CLO managers.

However, as exclusions in CLOs are mainly threshold-based, rather than following an absolute approach, it can be difficult to limit exposure to certain industries completely within multi-asset ESG fixed income funds that include securitised products.

CLO manager ESG evaluation processes

The interviews also revealed that investors rely significantly on CLO managers to conduct ESG due diligence, especially in the case of dynamic CLOs (i.e. those whose assets are actively managed on a discretionary basis). As they are responsible for selecting and purchasing loans and creating the capital structure of tranches (with varying risk and return expectations), it is important that CLO documentation is clear, to ensure the systematic incorporation of ESG factors in their investment decisions.

A review of the final offering circulars for 16 European CLO transactions – known to include ESG features – from 12 CLO managers, priced between March 2018 and July 2020 (see Figure 4), revealed the following:

- Legal documents accompanying the CLO transactions were not standardised. In most cases, only one or two key ESG terms were defined. In less than a handful, they were extensively defined.

- Many transactions did not outline a specific ESG evaluation process by the CLO managers and the standard care for assessment was variable.

- Five transactions gave CLO managers discretion to reasonably determine whether they complied with ESG eligibility criteria, based on the information available to them. This could include considering environmental issues and factors such as the relevant obligor’s ESG policy and track record. In another case, the CLO manager had sole discretion to determine compliance.

- When narratives offered investors some descriptions of CLO managers’ ESG evaluation processes, they were generally vague.

- Apart from such evaluation processes and barring one other case (see ESG CLOs: An exception below), negative screening was generally the only ESG feature of the transactions, with the most excluded sectors listed in Figure 19.

- Of the CLO transactions that set a revenue materiality threshold to determine what business activities to exclude, only two set the percentage exposure at a meaningful threshold of below 50% (at 10% and more than 30% respectively) – the other deals typically set it at over 50%.

ESG CLOs: An exception

One deal stood out because it added three ESG features to the industry exclusion criteria: diligence/asset monitoring, asset scoring and quarterly reporting. On asset scoring, the CLO manager had sole discretion to assign an ESG industry category and an ESG score to each collateral obligation, using an internal corporate and social responsibility toolkit and ESG checklist. Furthermore, the deal included an extensive description of the ESG approach taken by the CLO manager’s overall firm.

Figure 19: Most excluded sectors by European CLOs. Source: Offering circulars

The green and orange bar colours denote sectors that were excluded because of environmental and social factors respectively.

Lack of ESG premium

Another comparison of European ESG CLOs that were issued between March 2018 and August 2020 versus traditional CLOs, conducted by Deutsche Bank, shows no meaningful price differentiation between them. [22]

There are potentially several reasons for this:

- The sectors that are excluded from the CLO pool represent a relatively small share of CLOs’ investment universe – averaging just 3% according to a report by Moody’s Investors Services – as the exclusion thresholds used are relatively high. Therefore, the portfolio construction for deals with ESG criteria is unlikely to be very different from the traditional European CLO universe.

- ESG criteria are not standardised, so a premium cannot be priced.

- For now, the ESG label refers to the presence of diverse screening criteria and does not link the CLOs to specific (and measurable) environmental or societal outcomes.

- These are just preliminary findings, however, and should be interpreted with caution. [23]

Even if a spread discount versus regular CLO transactions is not yet apparent in ESG CLOs, it may emerge going forward, driven by growing demand for ESG-focused funds and more managers embedding ESG factors within their investment processes. As deal structures become more sophisticated and use increasingly stringent criteria, investors may be willing to pay more for these products.

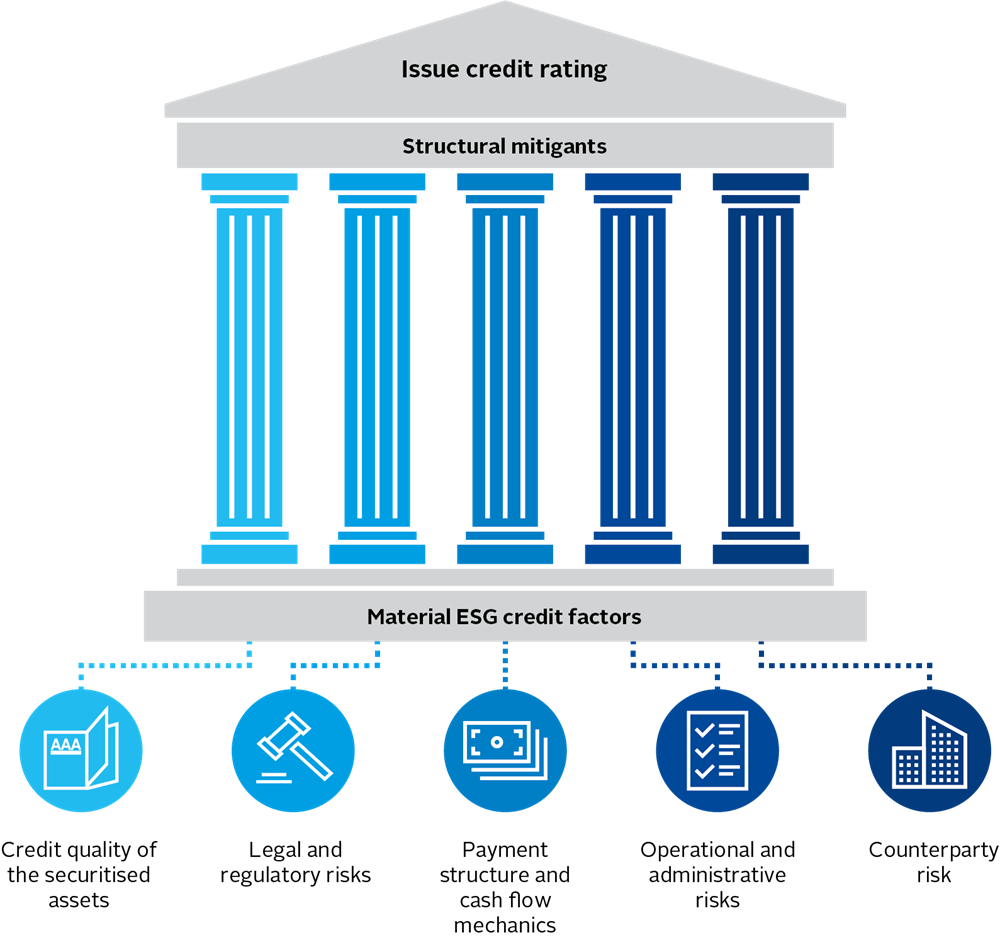

Credit rating agencies

Credit rating agencies play an important role in securitised products. Their rating opinions shape the priority payment structure, which determines the order in which creditors would get paid in the event of default (see Figure 20).

In turn, some investors may be limited to holding issuance of or above a certain credit rating – due to regulation (e.g. banks, pension and insurance funds), internal by-laws or portfolio hedging requirements.[24]

CRAs have sharpened their ESG focus in recent years. Since its 2016 launch, 26 CRAs have supported the PRI’s ESG credit risk and ratings initiative, while market demand for greater clarity on whether ESG factors drive rating actions and European regulatory scrutiny have also increased.[25] Many CRAs have created sustainability teams to work with credit analysts and are expanding their resources and analytical tools – some through the acquisition of ESG data and service providers – to deepen their ESG research.

Figure 20: CRA ratings shape the payment structure of securitised products

However, participants noted that CRA coverage of ESG issues in credit ratings varies significantly across asset classes and is lagging for securitised products, compared to corporate or sovereign bonds. Moreover, most CRA efforts have so far focused on ABS, RMBS and CMBS, rather than on CLOs. Examples of how CRAs are including ESG factors in their securitised product credit risk assessments can be found in Appendix 3.

The PRI will address the steps that CRAs have taken to clarify how ESG factors feature in their securitised product rating methodologies in a separate publication.

Challenges

Key messages:

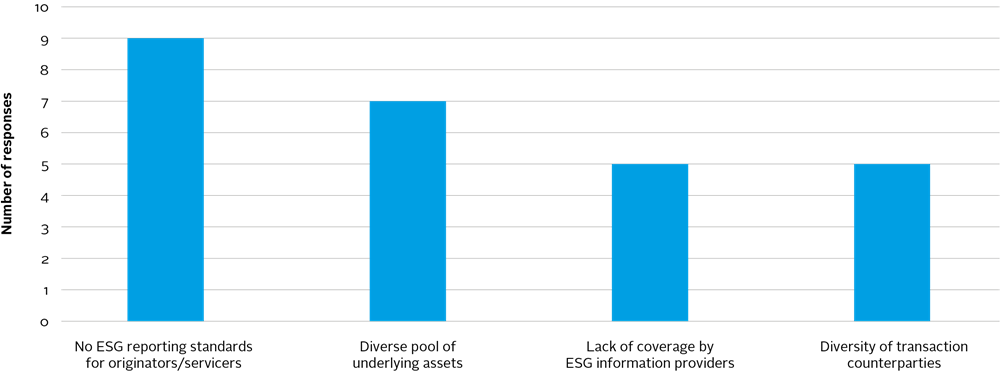

- The availability of adequate ESG data represents the main challenge to investors incorporating ESG factors in their securitised product credit assessments.

- Other challenges include the absence of ESG reporting standards for servicers/originators; the diverse pool of underlying assets; and a lack of securitised products coverage by ESG information providers.

Interview participants stated that the onus to investigate prevalent ESG issues in securitised products, particularly ABS, CMBS and RMBs, lies with them – the investment managers – rather than originators, sponsors or loan issuers. This makes the due diligence process cumbersome and difficult.

For responsible investment practices in securitised products to become more widespread, due diligence needs to be conducted throughout the investment chain.

Whether set by industry standards or defined by regulators, ESG parameters need to become deal-breakers, where a lack of adequate assessment by all transaction parties could lead to corporate liabilities, higher credit risk, restricted capital access for borrowers, and negative repercussions on asset valuations for asset owners and investment managers.

This relies on better information disclosure at all transaction levels, including obtaining ESG data on the underlying assets linked to securitised products, which represents a major challenge.

“In securitised products, we see the data gaps everywhere. Many CLO managers, especially in developed markets, have started tracking data surrounding the questions we are asking, but they don’t necessarily give it to us right away as part of their regular disclosure.”

US investment manager

Data collection

Practitioners consider the ESG information in current deal documentation, marketing materials and underlying portfolio disclosures insufficient to comprehensively analyse most securitised products.

The tables below highlight what ESG information is available and what investors are looking for, by product type, as well as some of the questions that they are starting to ask (see Figures 21 – 23).

“We try to ascertain ESG-specific factors from the deal documents; however, there is not much standard ESG disclosure in these with respect to environmental and social factors.”

European investment manager

Figure 23: Specific questions related to ESG incorporation by product type

Other investor challenges

We asked participants to cite other major barriers to implementing ESG considerations when investing in securitised products (see Figure 24). These included:

- No ESG reporting standards for servicers/originators: Relevant ESG information on collateral often lacks uniformity and is not comprehensive, especially for non-agency deals. However, some respondents highlighted that alternative methods, such as advanced artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques, could support investors conducting ESG analysis.

- A diverse pool of underlying assets: The complexity and diversity of underlying collateral (and the sectors covered) make it difficult to build proprietary ESG frameworks that can be used for assessment.

- A lack of coverage by third-party ESG information providers: ESG information providers have limited coverage of securitised products. This is not surprising given that responsible investment originally developed in equities and only recently expanded to debt capital markets. Moreover, the leveraged finance market includes a high proportion of privately owned and small-cap companies that tend to disclose less information. However, this may change, as investor demand for these products is rising.

- The diversity of transaction counterparties: Respondents said that getting information on a deal’s counterparties – issuers, originators, sponsors, CLO managers, trustees, guarantors and servicers – and assessing their individual practices and policies can be challenging.

Figure 24: Other major challenges to systematic ESG incorporation in securitised products

Based on 21 responses. Respondents could make multiple choices.

Next steps

This report outlines a range of challenges and issues surrounding ESG incorporation in the securitised debt market that need to be addressed. There are clear benefits to doing so, including a likely increase in capital flows, tightening potential within pricing and increased engagement between companies and investors on ESG issues. Ultimately this can drive favourable outcomes for all parties, including asset owners, stimulate real-economy lending to sustainable economic activities and contribute to a post-COVID-19 recovery.

The PRI intends to support securitised credit market participants to improve the quality of their ESG incorporation and the real-world outcomes arising from their investments.[27]

The steps we outline below look to provide solutions to the primary challenge – data quality, availability and consistency. A combination of robust in-house and third-party data sources is likely to drive investor confidence in ESG incorporation across securitised credit markets. Investment managers have started to develop internal ESG data collection, scoring and rating frameworks, but more action is required.

Improve investor-issuer dialogue and transparency

In the absence of regulatory mandates to improve the quality and relevance of ESG data disclosure, the PRI will build on two existing initiatives that are applicable to the securitised market. Through the workshop series, Bringing credit analysts and issuers together , we will continue to facilitate dialogue between corporate borrowers, investors and CRAs to improve data disclosure and investor engagement on ESG topics.

The PRI has also supported the European Leveraged Finance Association in the development of sector-based ESG fact sheets , which should increase transparency in the leveraged loan market and enable securitised product investors to enhance their analysis. [28]

Stakeholder collaboration

The PRI will also explore how it can work with other stakeholders in the securitised credit market. This report, and work completed elsewhere, highlight that investors cannot solve the challenges they face alone and that collaboration with the following stakeholders is necessary:

- Banking industry: to harmonise ESG loan criteria and build a common framework to assess borrowers’ commitments to environmentally and socially sustainable economic activities.

- CRAs: to enhance the transparent and systematic consideration of ESG factors in credit risk assessments, given the central role they play across all aspects of securitised products. Through their access to investors, corporate borrowers and significant amounts of underlying information, CRA opinions can increase investor confidence and capital flows into sustainable investment activities.

- Third-party ESG information providers: to enhance the availability of independent information, supplementing that provided by CRAs.

- Legal industry: to help develop robust, standardised legal documentation with binding obligations that would make the market’s ESG adoption more credible. This will increasingly become a focus in Europe, where impending regulatory changes will require greater clarity on what can be designated an ESG-compliant asset or investment.

- Arrangers: to effectively market the merits of ESG transactions and influence the behaviour of market participants. Clear evidence from the green bond market shows that there is significant investor demand for these products, which arrangers can demonstrate to investment managers. Increased issuance of ESG securitised products is likely to increase pricing differentiation across the market.

Broaden signatory understanding

The securitised debt market is largely concentrated in the US and Europe, with a small but growing presence in other geographies, and could become an important funding source for environmentally sustainable activities going forward. The PRI will work with our global signatory base to extend its understanding of ESG incorporation practices in securitised products.

Sharing best practice

The PRI will collect case studies to illustrate how investment managers are addressing client requests and extracting relevant information from issuers, driving progress and showing leading practice.

The PRI welcomes signatory case study contributions and feedback from market participants on this report, as it considers how to support stakeholders in improving data transparency, disclosure and engagement in the securitised products industry.

Appendix 1: Securitised products questionnaire

General information

1. Please describe your role in your current organisation and your area of specialisation in securitised products (CLO/ABS/RMBS/CMBS/others)?

2. Has your organisation started incorporating ESG factors in a systematic manner when assessing/valuing securitised products?

3. If yes, why?

4. Do you or your team conduct the ESG analysis or do you have a dedicated ESG team? If so, how do you interact with it?

5. Do you source the data for the ESG analysis internally or do you use third-party data?

6. Do you have a public document that describes your ESG consideration policy in general and on securitised products specifically? If yes, please provide a copy or a link.

CLO-specific questions

Data requirements for ESG integration

7. What type of data is difficult to find or not available and how do you overcome such data gaps?

8. Beyond data, name two or three significant challenges for incorporating ESG factors in a systematic manner.

9. Do you carry out an ESG analysis on the collateral and if so, how?

10. Do you evaluate the structural components of the SPV from a governance perspective?

11. How do you assess the industry ESG risk (internal assessments, rating agency view, client demand, others)?

12. What ESG factors do you look out for in the deal documentation?

13. Do you engage with Credit Rating Agencies on ESG topics specifically associated with securitised products?

14. Do credit rating opinions disclose the material ESG factors considered transparently and systematically?

Stewardship

15. What ESG information from CLO managers would be helpful to be disclosed in the transaction documents and report?

16. How do you assess the CLO managers’ ESG expertise?

17. Have you declined any CLO investments due to ESG reasons in the past?

ABS/RMBS/CMBS-specific questions

Data requirements for ESG integration

18. What type of data is difficult to find or not available for ESG consideration in ABS/RMBS/CMBS and how do you overcome such data gaps?

19. What ESG factors do you look out for in the deal documentation?

20. At which level do you consider ESG factors (originator, servicer, counterparty)? If you differentiate, what ESG factors do you consider to be relevant at each level and why?

21. Do you focus on the same ESG factors for all types of consumer-focused ABS or do you differentiate by underlying sector, e.g. auto loans, student loans? Do you distinguish whether the loans are prime, near-prime, subprime?

22. What factors and sources of data are evaluated to assess environmental (including climate) risk, societal and governance factors?

23. For ABS/MBS backed by non-static portfolios, how do you monitor ESG factor changes?

Stewardship

24. Do you engage with originators/servicers/counterparties/CMBS counterparties on ESG issues?

25. When assessing ABS/MBS, to what degree do you find ESG factors applied between collateral, securitised and origination policies?

26. Have you declined any ABS/RMBS/CMBS investments due to ESG reasons in the past?

Appendix 2: Regulatory developments

Interview participants pointed to several regulations and initiatives that could affect the relevance of ESG factors in securitised product analysis. A few of these, relevant to Europe and the United States, are listed below. Investors are also scrutinising regulations and policies in other countries, such as China, the UK, Australia and Canada, that support, encourage or require them to consider all long-term value drivers, including ESG factors. For an extensive list, readers should refer to the PRI’s regulation database.

Europe

Since the EU Commission launched its action plan on sustainable finance in 2018 and the European Green Deal in 2019, it has passed several regulations. These include the SFDR and the EU taxonomy for sustainable activities – a classification system establishing a list of environmentally sustainable economic activities. It is also working towards an EU green bond standard.

In particular, the SFDR requires financial market participants, including investment managers, to publish how they integrate sustainability risks in investment decision making. At the product level, it requires them to disclose how they consider the principal adverse impacts which investee entities may have on sustainability factors. [29]

United States

Although in its infancy, the new US administration has already taken several steps which could positively impact responsible investment practices – namely:

- its recommitment to the Paris Agreement;

- its Green New Deal proposal;

- the SEC has requested public input from investors, registrants and other market participants on climate change disclosure; and

- the Commodity Futures Trading Commission has established a new climate risk unit.

Even at a state or city level, there have been some interesting developments. For example, 45 of the 100 largest US cities have active and fully formed climate action plans, with many targeting 80% greenhouse gas emission reductions by 2050 in accordance with the Paris Agreement. [30]

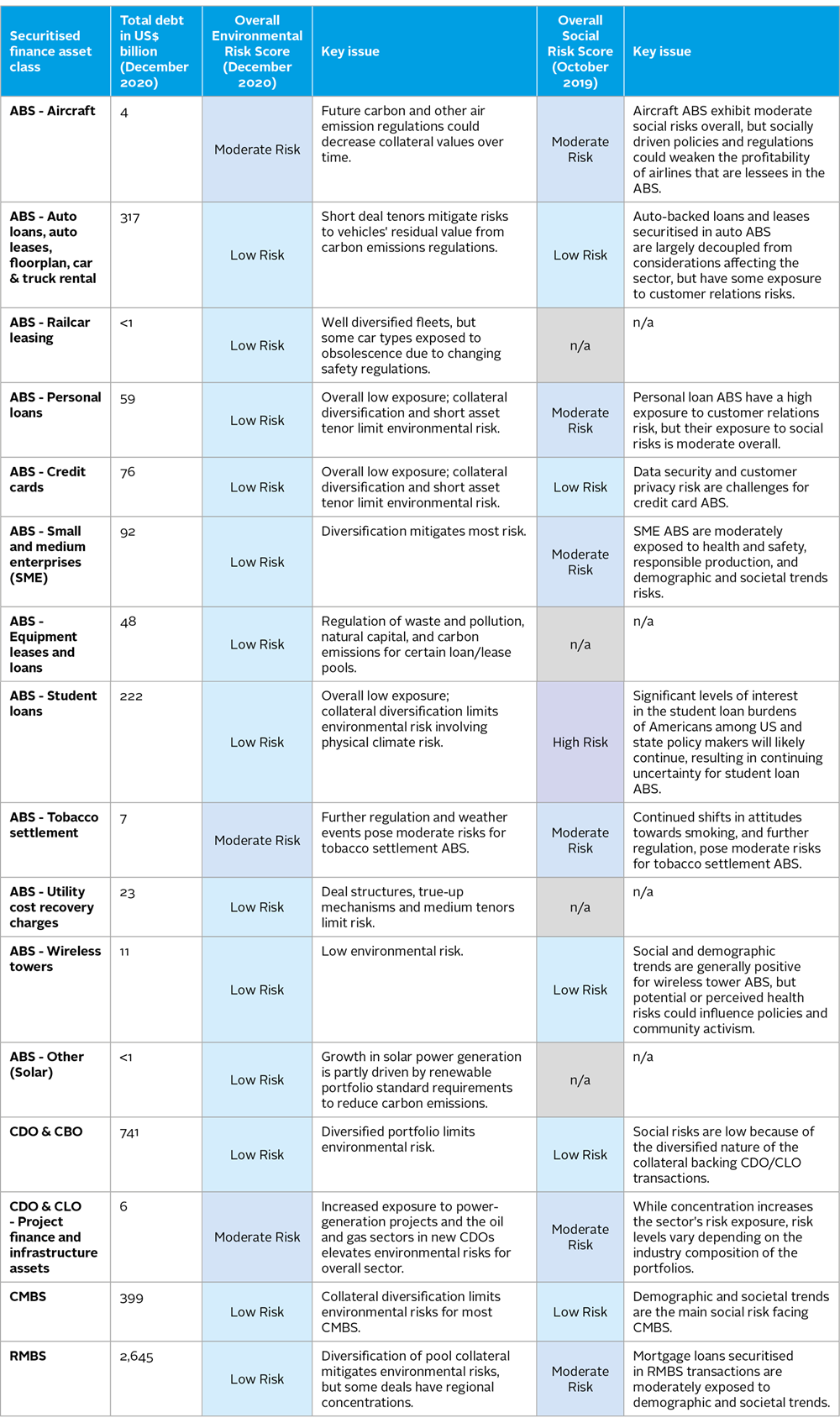

Appendix 3: CRAs and ESG factors

Below is a summary of how selected CRAs (listed in alphabetical order) consider ESG factors in their credit risk assessment of securitised products.

Fitch Ratings

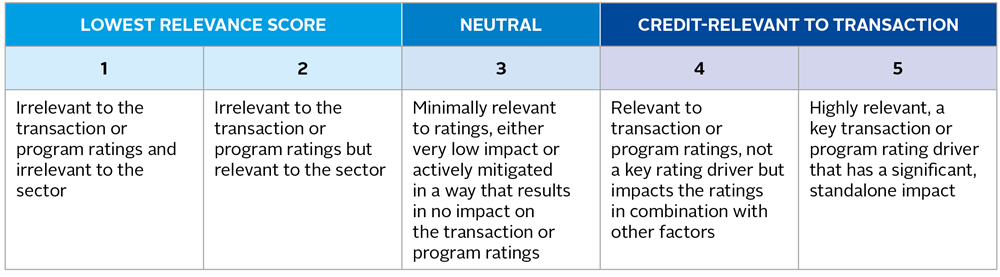

We have developed an ESG Relevance Score (ESG.RS) that assesses the credit impact of 14 ESG factors across our rated ABS/CMBS/RMBS and covered bonds (CVB) portfolios (see Figure 25). We assess the transaction structure for environmental and social issues and the transaction originator for governance issues. We also monitor the ongoing management of the transaction, and any asset substitutions, for governance issues. We assigned approximately 64,232 ESG.RS on 4,588 securitised finance and CVB securities as of January 2021 – just over 2% were assigned an ESG.RS of 5 and approximately 16% a score of 4 in at least one of the 14 categories.

Figure 25: ESG scoring definitions. Source: Fitch Ratings

Environmental categories typically do not impact securitised finance and CVB rating analysis but can be material to some US RMBS transactions that are exposed to catastrophe risk. Social categories are highly relevant, predominantly due to underlying consumer-based assets (for example, pending litigation related to US student loan transactions). We do not score securitised and CVB products less than 3 on governance because it is always deemed to be at least minimally relevant.

Kroll Bond Rating Agency (KBRA)

Our priority is to evaluate factors that may meaningfully influence credit analysis (see Figure 26). Some of these may be ESG factors, depending on the securitised asset type. Environmental factors such as increased regulations, contamination, and natural disasters, have the potential to affect asset values and, therefore, our evaluation of credit quality.

In ABS, various environmental laws and regulations may negatively impact certain industries. For operating assets, the manager’s response to such regulations is evaluated. For CLOs, managers may have to target or avoid certain sectors based on environmental or social externalities, which may impact performance. For CMBS, contamination can impact property values – this is evaluated through the analysis of environmental reports and/or related issuer data. For RMBS, CMBS and certain ABS transactions, collateral can also be adversely impacted by natural disasters, which if uninsured, could lead to loan delinquencies.

As part of our rating process, we consider demographic trends, employment levels, and consumer behaviour, amongst various social factors. Governance analysis typically includes a review of transaction counterparties and structure, with weaker governance provisions or nonstandard features in deal documentation potentially influencing our ratings.

Figure 26: Credit relevancy of ESG factors. Source: KBRA

Moody’s Investors Service

We typically incorporate ESG considerations across credit ratings [31] , although doing so is difficult and entails qualitative judgment, because it must often be inferred from multiple sources, based on reporting that generally is not standardised or consistent.

When assessing environmental risks, we may assess how emissions regulations affect automobile residual values for securitisations backed by automobile leases. Social factors such as the ageing baby boomer generation will likely increase demand for reverse mortgages, while millennials choosing to rent rather than own, or vice versa, would affect demand for single-family rentals, with implications for RMBS credit quality. Governance risks are largely transaction-driven and can be mitigated by a strong control mechanism in the transaction documentation. An example of our assessment can be found in Figure 27. [32]

Figure 27: Environmental and social heath map in securitised products. Source: Moody’s Investors Service

S&P Global Ratings

Our rating analysis of securitised products transactions is based on five key pillars (see Figure 28). We only view ESG factors as credit relevant if they are material enough to influence our view of risk for any pillar. Strong ESG credentials do not necessarily indicate strong creditworthiness. Even when relevant to credit quality, they may not impact the credit rating if a transaction’s legal and structural features can mitigate them (e.g. credit enhancement, short tenor, deleveraging, concentration limits, eligibility criteria). ESG credit factors that could affect an issuer’s (corporate or sovereign) credit rating may not be material to a securitised product credit rating, which is issue specific, and vice versa.

Obligor or geographic concentrations may increase exposure to physical climate risks. Social factors such as high interest rates and affordability considerations, or aggressive collection practices, could increase legal and regulatory risk. Most securitised products transactions have relatively strong governance frameworks because the roles and responsibilities of each transaction party and the allocation of cash flows are well defined, and transactions are structured to isolate the assets from the seller. However, governance weaknesses at the originator or servicer levels could still have a negative rating effect.

Figure 28: ESG factors in S&P structured finance analytical framework. Source: S&P Global Ratings

Downloads

PRI_ESG_incorporation_in_securitised_products_2021

PDF, Size 2.79 mb

References

[1] Strictly speaking, ESG-labelled CLOs do not exist but this has become a widely used term in the industry and by the media, referring to CLOs that exclude certain industries based on selected ESG criteria.

[2] See Appendix 2 for more detail.

[3] Such as asset-backed securities (ABS), residential and commercial mortgage-backed securities (RMBS and CMBS respectively).

[4] The PRI’s fixed income resources can be found at www.unpri.org/investment-tools/fixed-income.

[5] These represent a fraction of the market and have diminished significantly since the global financial crisis and the sub-prime mortgage scandal.

[6]Appendix 1 contains the questionnaire that was used to conduct the interviews.

[7] Securities that are issued by US government agencies such as Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae.

[8] Association for Financial Markets in Europe, Citigroup

[9] Bloomberg, offering circulars, information subscription services

[10] Bloomberg, Intex, marketing materials, rating agency presale reports

[11] See FTSE Russell (2020) ESG taxonomy for securitised products, and PWC Luxembourg (2020) Parties involved in securitisation transactions.

[12] See https://www.unpri.org/signatories/reporting-and-assessment for more detail on the PRI’s reporting and assessment processes.

[13] Information on the terms and definitions used in the PRI’s Reporting Framework can be found in the glossary.

[14] Disparate impact is a US legal term referring to employment or educational practices that appear to be non-discriminatory but have a disproportionately negative effect on members of legally protected groups. See https://www.britannica.com/topic/disparate-impact for more detail.

[15] For more detail on how PRI signatories have improved their responsible investment practices, see The evolution of responsible investment: an analysis of advanced signatory practices.

[16] This question was answered by 21 respondents. They were able to select multiple answers.

[17]Morningstar (2021) European Sustainable Funds Landscape: 2020 in Review

[18] For example, the United Nations-convened Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance, an initiative for asset owners that have committed to transitioning their investment portfolios to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

[19] For example, France conducted a consultation to tighten Article 29 on ESG and climate change reporting. See Consultation on the decree under article 29 of the energy-climate law.

[20] This is in stark contrast to the deregulation enacted by previous governments. For example, the removal of risk retention rules when the collateral for CLOs is acquired in the open market. See 9 February 2018 US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit decision for more detail.

[21] Deutsche Bank does not accept any liability for any direct, consequential or other loss arising from reliance on this document. This communication and the information contained herein is confidential and may not be used for any commercial purposes nor reproduced or distributed in whole or in part without Deutsche Bank’s prior written consent. This material is based upon information that Deutsche Bank considers reliable as of the date hereof, but Deutsche Bank does not represent that it is accurate and complete. Deutsche Bank has no obligation to update, modify or amend this report or to otherwise notify a recipient thereof if any opinion, forecast or estimate set forth herein changes or subsequently becomes inaccurate. Details about the extent of Deutsche Bank’s authorisation and European and Germany Regulatory background are available on request or from https://www.db.com/legal-resources under the heading Corporate and Regulatory Disclosures.

[22] Fifteen CLOs issued in that period mentioned ESG factors in their marketing or offering documents. Deutsche Bank compared the publicly available weighted average discount margin (WADM) of 13 ESG CLOs with the WADM of the 3-month cohort median, which did not show any meaningful price difference. To adjust for the deal age and to make relevant comparisons, they compared each deal to deals issued in the same month along with those issued one month before and after, thereby forming rolling 3-month cohorts for each deal.

[23] The pricing difference is affected by which group the deal is compared with – if a static CLO or a CLO with a shorter reinvestment period was issued among CLOs with longer reinvestment periods in its 3-month cohort, it could appear to have a strong pricing benefit; or if a CLO was issued immediately after the market widened due to COVID-19 it could appear to have a pricing disadvantage. A CLO’s WADM could be affected by several other factors not considered in the comparison, including its tenor, the credit enhancement level of the structure or the CLO manager’s platform. The 3-month cohort can be constructed based on the pricing date or closing date – this comparison uses the pricing date. Deals that did not have a publicly available WADM were excluded.

[24] Voxeu.org (2019) Credit ratings and structured finance

[25] European Securities and Markets Authority (2019) ESMA advises on credit rating sustainability issues and sets disclosure requirements

[26] For example, Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design or Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method certification.

[27] The PRI’s 2021 Reporting Framework has already streamlined the reporting requirements for signatories, and, for the first time, asks them to report on how they measure the real-world outcomes of their investments, thereby encouraging them to think about the consequences of their allocation decisions. For more detail, see PRI (2020) PRI’s New Reporting Framework: driving positive change in responsible investment.

[28] PRI (2020) The ELFA and PRI host ESG workshop for advisers to sub-investment grade companies

[29] Implementing SFDR for securitised products will be particularly challenging, in the absence of a mandate to disclose ESG information by originators/servicers. It also remains unclear if the provisions requiring principal adverse impacts disclosure will apply to a product’s underlying assets or to its structure.

[30]Brookings Institute (2020) Pledges and progress: Steps toward greenhouse gas emission reductions in the100 largest cities across the United States

[31] Moody’s Investors Service (2020) General Principles for Assessing Environmental, Social and Governance Risks

[32] For more detail, see Moody’s Investors Service (2019) ESG – Global Heat map: Social considerations pose high credit risk for 14 sectors, $8 trillion debt and Moody’s Investors Service (2020) ESG – Global Heat map: Sectors with $3.4 trillion in debt face heightened environmental credit risk.