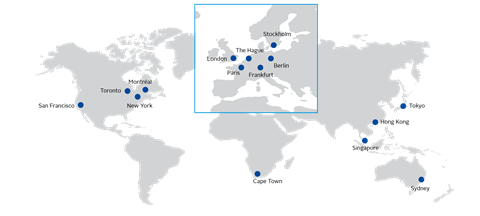

The forums that the PRI has organised globally have revealed regional differences on three levels: awareness and advancement of ESG consideration; relative sensitivity to ESG factors by country; and regulatory environment and attitudes towards it.

Awareness and advancement of ESG consideration

The most notable development on this front is the rapidly increasing level of interest that this topic is generating in Japan, as well as the pace of progress of ESG consideration in North America. The increasing commitment by Japan’s Government Pension Fund (GPIF) – the world largest pension fund – to ESG investing has stimulated interest among Japanese market participants (including institutional investors as well as local CRAs), with positive repercussions in other Asian markets.

In North America, where some of the most engaging investor-CRA discussions took place, pressures to expand product offering, spurred by client demand, appear at play in the US. In Canada, some investment managers and large AOs have passed the stage of ESG awareness and are actively working on incorporating ESG factors in investment practices, but many others are still assembling building blocks and have yet to step up the pace of embedding ESG consideration in existing practices.

In Europe, it was unsurprising that the level of progress on ESG consideration is more advanced in France, the Netherlands and Sweden, where ESG consideration started comparatively earlier. In Northern Europe, rules-based approaches have been the precursor of more mainstream ESG investing and engagement practices are more common than elsewhere. Even in Germany – one of the European countries where ESG consideration is lagging, despite its comparatively larger bond market – appetite for ESG consideration is growing.

Sensitivities to ESG factors

These vary significantly by country. For example, conversations around governance were relatively more prominent in Japan, and particularly so in South Africa; the South African market is also subject to capital controls and is more illiquid compared to other countries, making investment decisions more binary and with limited room for engagement. During the Hong Kong roundtable, the question of “moral hazard” regarding governance was also raised in relation to state-owned enterprises, where financing structures may be distorted by government guarantees.

Sensitivity to environmental factors also varied by country: some are more exposed to physical environmental risks than others – EMs more so than DMs. There was, however, growing appreciation during the European roundtables that these are becoming more regular in DMs. During most of the roundtables, the distinction between physical and policy risks (such as measures related to the transition to a low-carbon economy) was also flagged, with some participants asking CRAs to clarify which scenario underpinned their base-case assumptions.

Furthermore, the link between social factors and creditworthiness remains the most difficult to measure across the board. But some social factors – such as labour market conditions and labour disputes – are already on the agenda of some investors in selected countries (notably South Africa and Singapore).

Finally, sensitivities to ESG factors also vary also depending on whether institutional investors are AMs or AOs, given their different investment objectives and time horizons. This inevitably affects the weight attached to ESG factors. For example, participants of the Sydney roundtable were mostly AOs; their contribution highlighted that AOs are not yet clear about what to ask external FI managers about their approach to ESG consideration when they appoint them, nor how to ensure they comply with ESG policies. Many admitted that ESG consideration in credit risk is a new area and are in need of guidance.

The regulatory environment and attitudes towards it

Regulatory pressures are building up rapidly in several regions. The French Energy Transition for Green Growth Law, adopted in August 2015, marked a turning point in carbon reporting. More recently, in Europe, the work of the High-Level Expert Group on Sustainable Finance and the subsequent EU Commission Action Plan, published in March 2018, have incentivised credit practitioners to sharpen their focus on ESG issues.

Another example is Canada, where, in 2016, Ontario became the first province to require local pension funds to disclose the extent to which they invest sustainably, and if so, how ESG factors are incorporated into investment policies. Furthermore, in 2017, the Canadian Securities Administrators launched a climate change disclosure review project, partly in response to institutional investor demand for improved reporting in this area. And, this year, the Canadian Ministry of Environment and Ministry of Finance appointed an Expert Panel for Sustainable Finance in Canada to consult on this topic with a wide range of stakeholders.

However, in certain countries, regulatory intervention is perceived more as a threat (which may trigger pre-emptive action in the right direction). In others, notably some Asian countries, regulation is welcomed as a propeller of change.

In part one, we highlighted the importance of credit ratings in sovereign debt, with the government debt market by far the largest across FI instruments (p. 20). Also, since the global financial crisis, the share of government bonds with AAA ratings by the largest three CRAs has been shrinking, in a sign that even assets once perceived as safe havens are not immune from credit risk.

Download the report

-

Shifting perceptions: ESG, credit risk and ratings: part 3 - from disconnects to action areas

January 2019

ESG, credit risk and ratings: part 3 - from disconnects to action areas

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

Currently reading

Currently readingRegional colour from the forums

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25