This chapter focuses on ESG in investment decision making and portfolio construction, as well as on the risk and return framework.

Questions on how investment decisions are made, how information is interpreted and what information is available are considered. How a manager perceives risk and return, and how that view can be used to invest with an ESG mindset, will also be discussed, along with screening and integration processes.

Questionnaires can be a useful information-gathering tool for many of the themes discussed in this chapter. Few questions require examples, but the majority are well suited for a RfP/DDQ-type of document. However, while mechanistic investment processes can be covered in questionnaires, a thorough assessment of ESG in portfolio construction and decision making requires direct interaction between an owner and a manager.

One issue that asset owners often face is when a manager’s public report covers institutional aspects, with limited product-level information. Services that provide product-level information on portfolio holdings exist, and as part of their reporting to the PRI investment managers answer questions on ESG incorporation processes at the firm level. However, true understanding can only be gained from well-executed dialogue.

Investment decision making

An investment manager’s decision-making process must facilitate the realisation of an asset owner’s ESG imperative. Investment managers must ensure that investment processes incorporate ESG analysis, and that such insight is presented to investment decision makers (and that those decision makers are able and empowered to act accordingly).

For example:

- With active management and investment committees, either a designated and informed member brings ESG considerations to the attention of the committee, or all members are informed and targeting or actively considering ESG factors when they make investment decisions.

- With a quant process, the algorithm would be designed to embed ESG insight and use ESG data as input.

History shows that ESG incorporation is likely to be less present in investment processes than is often anticipated at a first glance of policies and process descriptions in marketing literature. For example, in fixed income, the PRI found in its recent work on credit ratings: ”It (ESG consideration) can be advisory in nature and the responsibility often falls on ESG analysts alone to raise ’red flags’. Hence, at this stage, full ESG integration appears some way off.” These observations are also supported by recent IRRCi/Sustainalytics research on ESG integration.

Approaches to ESG in investment decision making

Descriptive

Descriptive ESG generally means rules-based, as opposed to normative ESG or principles-based (discussed below). Descriptive ESG works well for some asset owners due to its simplicity and ease of execution. These types of measures and structures are relatively easy to assess when selecting an investment manager. They are also easier to implement in the appointment phase and to monitor and report on. Nevertheless, it is important for asset owners to understand the impact and limitations of such measures. For instance, if a company is on an exclusion list, does that mean it should be disinvested from all portfolios? And, if so, in what time frame? Further considerations on how assets are subsequently allocated, such as in the index, or only within the sector from which the company was removed, must be considered. When a descriptive measure is used, asset owners should prescribe a list of rules.

Questions:

- Do you have an ESG exclusion or inclusion list, and what governs these exclusions? Do you remove companies from the portfolio for non-compliance with the ESG policy?

- Do you blacklist countries and issuers, and which issues do these relate to (e.g. corruption, corporate governance, etc.)?

Normative

Normative ESG generally means principles-based, as opposed to being descriptive or rules-based. In cases where ESG incorporation requires a higher degree of judgement by the investment manager, measuring compliance against an asset owner’s ambitions and objectives is more complex. Asset owners must understand if there are tangible metrics to evaluate ESG compliance, and work on creating them if they do not exist. For example, if a product needs to be managed with the objective to remain within a +2 degrees scenario, an investment manager would need to demonstrate how this is being adhered to. This is a complex process for which a descriptive approach would be inappropriate. Elaborating on the process and using measures of judgement and best practices would be a more effective approach.

Questions:

- Please describe how you merge financial and ESG criteria during investment analysis.

- How often do you review the ESG risk exposure of the portfolio and how often have you changed the investible universe based on those findings?

Asset owners should verify that final decision makers use available ESG materials and organisational insight in their investment decisions. They should also ask prospective managers to support any claims with evidence and real examples to avoid “integration-washing”. The PRI recently published a guide that discusses ESG integration in public equity portfolios. The guide provides further considerations and case studies for asset owners when it comes to understanding ESG factors in investment decision making.

Risk-return framework

Risk

There are myriad views on and definitions of risk. For example, an asset owner may perceive risk as the likelihood that a result does not align with its long-term investment goals or as surplus risk. For a long-only investment manager, risk is usually associated with deviation in return versus a benchmark. For an absolute return fund manager, risk is often defined as not meeting a fixed return target.

Asset owners must be clear about what risk means to them at each level of the investment process, and how it can vary across their portfolio. This is particularly important as measures of risk linked and monitored in manager relationships for investments within a portfolio may not always reflect an asset owner’s long-term goals and overall plan perspective.

An asset owner’s ESG or strategic risk framework needs to be embedded in mandates and followed through in the selection process. One cannot expect that buying into a mutual fund tracking the S&P 500 Index without exclusions or tilts will comply with an investment policy or strategy that states: “We see carbon exposure as the biggest investment risk to our long-term performance”. Likewise, reputational ESG risks such as potential labour and environmental controversies in an investment portfolio should be identified in an asset owner’s investment policy (and averted).

With expanding understanding of risk premia and sophisticated portfolio risk analysis, asset owners are more able to uncover ESG relationships with all traditional risk measures. The selection process should test a manager’s ability to supply relevant analysis.

Return

Returns alone and ESG outcomes specifically are treated and targeted in different ways by asset owners and investment managers. This may be due to differing commercial strategies, investment competency, legal, fiscal and tax systems, and may also reflect alternative perceptions of fiduciary duty.

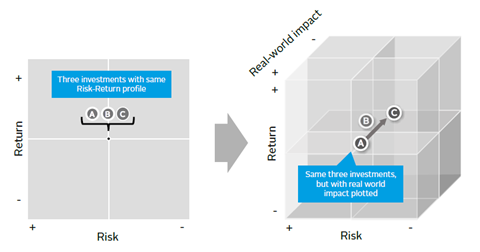

The PRI’s Asset owner strategy guide: How to craft an investment strategy guide encourages asset owners to explore their views on megatrends influencing the future investment environment and real economy impacts to determine how their institution can best generate returns (see here for a recent report on megatrends). As the diagram below demonstrates, for some market participants, investments only have financial risk and return aspects, while for others a third dimension – real world impact – is also contemplated.

Investments always have several real world impacts that can be positive and/or negative (for example, they may increase or decrease pollution levels, generate corporate and income taxes, support employment, create discrimination or be inclusive, etc.) and are intertwined with long term prosperity. Asset owners and the investment chain more generally that limit analysis to the two main dimensions covered in the diagram (risk and return) are missing a crucial element in their portfolio’s contribution to end beneficiaries and society as a whole.

Ideally, a manager will deliver positive real world impact that is aligned with an asset owner’s needs as an integrated aspect of their risk and return considerations. Clarity on real economy expectations during the selection phase will help to align interests for a productive long-term commercial relationship.

Portfolio construction

In portfolio construction, it is not just a question of what goes in, but how much goes in. Parameters like tracking error are important as they directly influence choice of investments, but may not be critical.

Portfolio construction (stock selection) is arguably more important for active than passive managers, as deviations from a benchmark determine their success. However, portfolio construction should not be underestimated in a passive context, particularly when passive strategies extend beyond pure index replication.

For example, an asset owner might have a mandate which screens (ESG or non-ESG) out stocks that represent 5% of the investable universe. If the tracking error needs to be kept similar to the pre-screen level, that 5% then needs to be allocated to the other names within the index. The allocation could be divided equally, weighted towards names with better or even worse ESG scores, or with a lower carbon footprint; names with the highest correlation to the stocks removed from the index; or derivatives can be used to create exposures, etc. All options have consequences. Removing holdings with the highest carbon footprints may result in an over-allocation to the lowest carbon performers in the sector or an index, impacting correlations and shifting expected risk and return among other portfolio characteristics. In some cases, such as if countries are removed based on ESG ratings or issues, only a very narrow investable universe may remain. This could hinder portfolio construction by introducing capacity constraints or impacting liquidity.

Thematic and screening approaches

Thematic and screening approaches choose investments in securities that fit into certain criteria and play increasingly important roles in asset allocation considerations. Asset owners should pay close attention to the methodology, rules and accuracy of chosen screens during the selection process.

Aligning exclusionary policies with international conventions

One way an asset owner may approach negative screening is to align its exclusionary criteria with the United Nations’ system of internationally-agreed conventions. For example, UN Global Compact has recently excluded from its membership companies that participate in tobacco and controversial weapons sectors – leading many investors to also reconsider their involvement. See more on tobacco exclusion on UICC and Tobacco Free Portfolios.

For example, a positive screen where 50% of the top ESG performers are included in an index can be executed by analysing all the stocks in-house, by licensing an index or using ESG scores to design a screened portfolio. A question here would be which process is the asset owner comfortable with and how would choices be reflected in fees charged.

Another example where accuracy would be a crucial element is a negative-screening product where a significant reputational risk item for an asset owner is excluded. How can a manager assure that the portfolio is always compliant? A discussion on the reallocation of an investment that has been screened out would also be needed.

A themed investment screen might target companies where women represent over a certain percentage of management, or bonds that finance social projects. The quality of data used for screening is important, including: the use of ESG ratings (how often ratings are updated); the use of carbon footprinting (scope of the exercise); and the use of indexes that satisfy particular thematic requirements. It is important to understand how managers can overcome liquidity issues in thematic products, funds or indices construction in areas where the underlying supply is limited.

Selection processes targeting alternative or smart beta products must consider how the index, with its inclusion of ESG considerations, alters the desired single or selection of active beta factors.

Integration

Integration relates to the process of embedding ESG considerations into fundamental investment valuation and related engagement, and applying insight acquired to investment decisions. For detailed examples in equity, please refer to the PRI’s A practical guide to ESG integration for equity investing. The chapter entitled Assessing external managers outlines what asset owners need to know about integration. In the manager selection phase, a key objective for asset owners is to assess the quality of a manager’s integration practices against their own expectations.

An intuitive way to ascertain the effectiveness of an investment manager’s integration approach is to consider the price of an investment firstly with, and then without, ESG factors accounted for. ESG integration should produce distinct outcomes in asset price, Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) models, credit spreads, internal rates of return, etc. – or an explanation as to why there is no difference. The investment manager should be able to attribute some value and/or have an informed discussion on the topic and why integration is applied – or indeed why it is not applied. Understanding what drives the valuation differential will help asset owners understand the integration process, and sheds light on how the prospective management team plans to select investments.

Activities portrayed as “integration” often merely amount to simple screening, whereas integration done well is a powerful method of fundamental analysis. From a value for money perspective, the importance of understanding integration is heightened as products claiming ESG integration are active products and levy active product fees. It is important that those asset owners that are willing to pay for genuine insight receive such insight and, ultimately, investment performance.

Impact investments

While still a niche market, impact or environmentally and socially-themed investment volumes have grown considerably over the last decade. Indeed, the PRI is currently working on an Impact Investing Market Map that gives information about 10 types of impact investments. The map helps investors understand the criteria that can be used to identify if and how these investments contribute to sustainable outcomes.

Asset owners that wish to include impact investments in their portfolios should seek to understand how their managers define impact and how they seek to measure such impact. One problem facing the industry is the branding of certain funds as impact investments without a clear link to impact contribution. It is therefore vital that asset owners help to maintain the integrity of the market by choosing products and funds that genuinely deliver positive impacts. Impact investments tend to be concentrated in private equity and debt investments.

Download the full report

-

Asset owner guide: Enhancing manager selection with ESG insight

March 2018

Asset owner guide: Enhancing manager selection with ESG insight

- 1

- 2

- 3

Currently reading

Portfolio construction and investment decision making

- 4

- 5

- 6